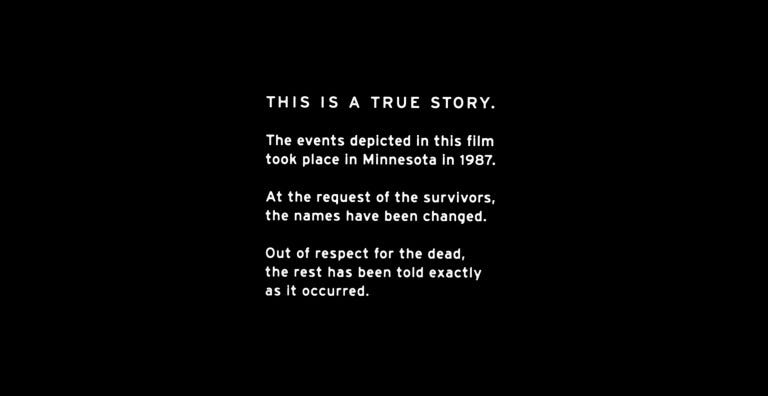

If you’re my age or older, when someone mentions “Fargo” your first thought is less likely to be “Oh! That’s a town in North Dakota” than it is “OH! That’s a great true crime movie by the Cohen Brothers!”

True crime?

Well, yes. It said so right in the opening:

So Fargo is history, right?

Yeah, right.

According to Joel Cohen, the film’s writer and co-director, the entire film—dark comedy that it is—was a satire on the then-popular raft of “based on a true story” films that had almost no resemblance at all to their putative source materials.

That title card is (literally) a joke.

Using the Truth to Tell Lies

One of the fun—and also irritating—parts of history is how little reliable information we have about most of the great figures of the past. Everyone agrees that Socrates, Alexander, Julius, Plato, and Darius were important, and mostly everyone agrees on why (more or less), but try to get an idea of who they were...well, you could literally devote a lifetime to trying to build a consistent picture from what survives.

Not that more evidence would make life any easier.

I trust you’ve heard the maxim “History is written by the victors”? It’s not really true—most of the great ancient histories that remain are written by defeated peoples who are either trying to suck up to the new regime or explain why the wrong side won the war—but it does highlight an important consideration when studying a narrative field like history:

Everyone who has enough of a burr under their saddle to bother to write history has an agenda (rather like happens with today’s news media). You certainly can’t afford to naively take anyone at their word. If a writer gives you a preamble attesting to his intent to faithfully relate the facts, and then he unfolds his narrative in the form that resembles the novels or epics of the era, you can safely treat the preamble like the preamble of Fargo: scene setting for fiction.

Narratives unarguably based on true events (such as Homer’s Illiad or Plato’s Apologia) aren’t much more reliable, nor are straight works of history such as Suetonius’s The Twelve Caesars. Those works that survive were written for a reason. The Apologia was written to defend Socrates’s reputation. The Twelve Caesars was written to defame the Julio-Claudian dynasty of Roman Emperors. They’re great books, and they have much to offer in terms of intellectual and historical value, but they’re not exactly disinterested reporting.

The legacy of all this makes for fertile culture-warrior action in the present day.

Take, for example, Netflix’s latest excursion into history which, at the time of this writing, is providing entertaining culture war fodder on Twitter. It’s a biopic series about the life of Alexander the Great, the Macedonian king (and student of Aristotle) who took off with a band of buddies and conquered the world from Egypt to the eastern border of India. He was 22 years old when he started off (it wasn’t his first military campaign), and 32 when he died somewhere on the subcontinent.

How did he die? Was he poisoned? Did he get malaria? Was he injured?

We don’t know.

What we do know is that he had a good friend from childhood named Hephaestion, and their relationship was close enough to raise more than a few eyebrows. One joke in the ancient world was that, while Alexander conquered the world, Hephaestion’s thighs conquered Alexander.

Beyond jokes like this in the ancient record, there just isn’t enough that survives to tell us that Alexander was definitely gay. We know he had a wife, and we know he attended a school where pederasty was practiced, but that’s about it. Smart money, in considering the full context, is that Alexander was probably what we’d call bisexual, but since the ancients had no such categories and didn’t really consider such things worth commenting on most of the time, we can never be sure.

As a result, Alexander has become a kind of political football, the kind that everybody lies about. If anyone can be said to be the progenitor of the entirety of Western culture, it’s Alexander—it was he who laid the groundwork for the Roman empire, and the Western world is the child of Rome. Therefore, any cultural faction that can successfully claim Alexander as their own can then claim to own the West.

Identitarians in the queer community have long (and pretty plausibly in my view) claimed Alexander was gay or bisexual (which in the identity politics game means he’s one of their own), while conservatives periodically push back and try to pretend that homosexuality was uncommon across history except during times of rank cultural decay. The results would be hilarious if they weren’t so transparently feeble:

There, in one tweet, you have both sides of a depressingly stupid culture war.

It does raise an interesting question though:

Why should we care? Are an historical figure’s contemporary identity markers (sex, gender expression, sexuality, religion, race, ethnicity, etc.) relevant to historical study at all?

Who Are You?

Let’s clear some ground first:

With the exception of “sex” and “religion,” none of our current identity categories map to the old world at all—and by “the old world” I mean “anything before the twentieth century” (and even that’s pushing it). There have always been people who picked sexual and romantic partners from their own gender, and there were always people who lived as the opposite sex in public (or who didn’t go that far but still took on the social roles of the opposite sex).

When we look back into the before-time, the sheer alien-ness of the world we’re looking into can’t be overstated. Almost nothing we WEIRDs (i.e. Westernized, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic people) take for granted about the way humans think or operate was true before our current era—and those things that are true had very different contexts and meanings then than they do now.

With all that in mind, let’s look at four prominent historical figures and consider whether their sexual identity markers were important to understanding how they moved the world:

First, consider Cleopatra VII, the last Queen of Egypt.

Egypt was in its waning years as an independent kingdom, and Cleopatra (herself a descendant of one of Alexander’s generals) went to great lengths to secure the protection of the contestants in the Roman civil wars that eventually brought Julius Caesar to the throne.

She did this first by seducing Julius Caesar (and bearing his child), and then, as the winds of fortune shifted, allying herself to Caesar’s great friend (and then bitter enemy) Mark Antony. Her willingness to use her sexuality as a political bargaining chip bought her a seat at the geopolitical poker table. Her inability to accurately read the political winds meant that her sexuality played a key part not only in her downfall, but in the end of the longest-lived empire in Western history.

It is impossible to reckon with Cleopatra’s legacy without engaging with her as a sexual being, therefore her sexuality is relevant. A parallel (and nearly opposite) case can be found in Queen Elizabeth I of England, whose determination to present herself as the second coming of the Virgin Mary (both in her dress, and in declining to marry, and in keeping her love affairs very private) played a key role in building the British Empire—and her lack of heirs similarly shaped everything that came after, including the very existence of the United States of America. Both of these titanic women’s sexuality—particularly its performative, public face—shaped history as much, and for the same reasons, as did the military genius of Tiberius or Hannibal.

But what of Cleopatra’s first Roman lover, Julius Caesar? His sexuality is no less relevant. While his affair with Cleopatra was a much smaller matter in his life than it was in hers, the competition for her loyalty with Mark Antony did eventually seal his rise to the role of sole Consul, which, in turn, led directly to his assassination. Despite that he had a child with her—his only natural child that we now of—it was his adopted son (and nephew) Octavian who finished Caesar’s great project of bringing an end to the Roman Republic and establishing the Roman Empire.

Alexander the Great is a more ambiguous case. While it’s certainly interesting that such a towering figure of masculine and martial virtue might also have been at least half-gay, the only real impact his putative inclinations left on the world was a vacuum. He had only one son that we’re sure of, and that one wasn’t even born when he died (men of his era—especially Kings, usually got to parenthood much earlier). Thus, when he died his empire was divided, and that division ensured a geopolitical environment that made the great, continent-spanning Hellenistic civilization easy pickings for Rome a few centuries later. And, of course, all these consequences are just as easily explained by his overwhelming love of war (at the expense of family life) as they are by his love of boys—in the end, it doesn’t matter to history whether Alexander preferred the sexual or romantic company of males, or just their military comradeship. The result, in either case, is identical.

Finally, let’s consider Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln was married and had many children, and had several romances with women before he was married, but his primary emotional attachment was to his best friend Joshua Fry Speed. The near rhapsodic devotion in their surviving correspondence certainly makes it sound, to modern ears, as if it was a romantic (if not sexual) relationship.

But at the time, this kind of thing was not at all unusual. Before Freud and his colleagues laid the groundwork for “sexual orientation” as a concept (which replaced situational descriptions of sexual acts between same-sex partners), the idea that affection and emotional devotion between best friends could be seen as indicative of a sexual relationship was barely conceivable. During that era—which was not known for its sexually liberal attitudes—men and women commonly enjoyed communal skinny-dipping, bed-sharing, hand-holding, and cuddling without ever raising an eyebrow. Even as late as the mid-20th century such friendships persisted in certain quarters (the friendship between C.S. Lewis and JRR Tolkien was of this character, and neither man was reputed to have homosexual inclinations). Given this context, it’s a real reach to posit that Lincoln was bisexual.

But if we were to posit that he was for the sake of argument, would it change our understanding of history?

Not really.

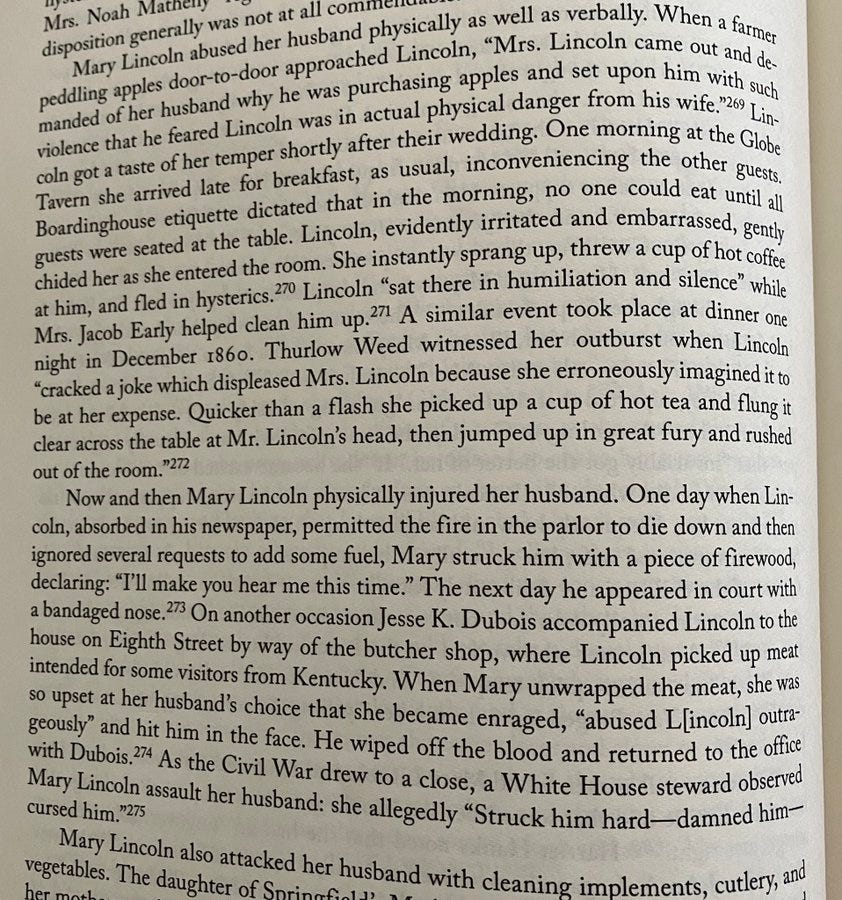

Lincoln’s relationship with his wife Mary Todd, on the other hand, is relevant to history.

The abuse he suffered at her hands doubtless stoked his tendency towards inflexibility and cruelty in his later years, gave him a deep reserve of violent temper, and is a typical entry in the biographies of tyrants throughout history.

Tyrants?

Remember that Lincoln not only prosecuted the Civil War with tactics we would now consider war crimes, he also had journalists jailed for the crime of criticizing him and fomented a plot to murder the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by charging him with treason (for the crime of ruling against Lincoln in a key court case).

The identity categories we use in our contemporary world are rarely relevant to understanding history.

Notice that I’ve talked about the sexual components of the oppression stack here, not the racial components. There’s a good reason for that: the ethnicity of historical personages has almost never been relevant to their accomplishments. Most pivotal historical figures operated within their native contexts. In the cases when they crossed racial or ethnic or cultural lines, these things usually mattered far less to their historic contributions than did the simple fact that they were outsiders. When it did matter, it mattered mostly in the form of the ideas they brought from their native culture that spread, because of their actions, to change the world they touched.

Moreover, before Carl Linnaeus subdivided humanity in the 18th century, the idea that all humans weren’t of the same “race” seems not to have occurred to anybody. Skin color certainly existed, but it wasn’t as important to social position as one’s family background, profession, and personal achievements—usually it was little more than a curiosity.

The Study of Great Figures

Up until the 20th century, most studies of history focused on the Great Men of History for a pretty obvious reason:

They’re the people (men and women) about whom historians wrote history books. Their deeds changed the world, and they were long remembered. Not a lot of history was written about the lives of ordinary people—instead, a knowledge of those lives was assumed by the writers of our primary sources. That’s great when you’re close to the events in question, but when you’re separated from the subject by years and cultural shifts and technological revolutions and language shifts, the context within which these Greats operated becomes harder and harder to access, and so the motivations for their deeds becomes more difficult to reconstruct. Judgments about their actions, therefore, become increasingly difficult to make.

Archaeology, which developed as a science in the 19th century, helped change this situation (we will examine how later in this series). As a result, since the early 20th century, histories written for the layman (i.e. you and me) have been able to include more of the context in which these figures operated. Some of that context has up-ended our understanding of these eras and their peoples—and, with it, our understandings of how we got here, and just how deeply unusual our WEIRD way of looking a the world truly is.

Unfortunately, the understandings of context enabled by archaeological discoveries are often unfriendly to all sides of the culture war, so they tend to get ignored (either cynically or out of ignorance) by purveyors of cultural narratives.

And so the propaganda mill spins on, in spite of better information being readily available.

Next time, we’ll look at these propaganda wars and how they explain the destruction of popular art in the past half-century—and why that destruction need not be permanent.

If you found this essay helpful or interesting, you may enjoy the Reconnecting with History installment on Understanding Before Thinking, and this essay on learning to think through language and story: Are You Fluent in English?

When not haunting your substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. You can find everything currently in print here, and if you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

I will never under how Conservatives, especially Christian Conservatives don't recognize that homosexual and bisexual actions were literally introduced in the very 1st book of the Bible. It has always, always been here.

I just finished the Alexander the Great series. I'm sure he was what we called bisexual, but as you pointed out, people just had sex. With whoever and whatever. They just didn't see it the way we do.

Lastly, I've read tons of old writing. The only time I ever see race applied is in a territorial way. As in, he came from the area of Libya or something. Or, when talking about the ways of this or that people. From what I can tell, they were always using MLK Jr.'s thought and treating people based on their character.