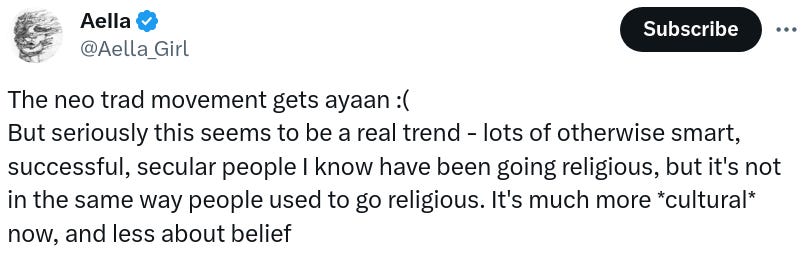

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, one of the world’s great heroes of freedom-of-conscience, announced her conversion to Christianity this week in Unherd magazine. In response, another exemplar of freedom-of-conscience and self-possession expressed her dismay thusly:

While I begrudge nobody a genuine conversion, in a macro-cultural sense there’s a lot more going on here than meets the eye. Since all of it connects back to the issues that animate this column, and stem from the various strains of history that we’ve dealt with here at Unfolding the World, I figured it would be a good subject to tackle here. What follows is a critique of an emergent culture-war strategy, not an attack on anyone’s personal beliefs. I hope you enjoy.

The Rise of the Neo-Trad

The last few years have been kinda weird in the renegade intellectual space. One of the most interesting developments has been the growing trend of self-described “liberals” and “leftists” to find themselves either becoming or traveling alongside a peculiar new flavor of conservative known as the Neo-Traditionalist.

Some definition is in order, because these aren’t your father’s conservatives.

Your father’s conservatives—the “Trad-Cons”—are the party of Pat Buchannan, Billy Graham, and Ronald Reagan. They came into ascendance in the 1950s and formed the basis for the Religious Right in the 1980s and 1990s.

The “Conservatives” that dominated the news cycle in the early 21st century are a different sort—the “NeoCons.” They ran the War on Terror and then moved into the leadership of the Democratic party after the election of Trump.

To understand how this new sort differs from these old sorts, we need to look closely at all three.

The Trad-Cons believe in good-old American can-do-ism and know-how, so long as it’s ensconced in a containment vessel that prizes “family values” such as chastity, repression, “male headship,” abstinence from most transformative experiences (most drugs, most role-playing-games, some sorts of rock-n-roll, etc.), and a devotion to God, Country, and a fairly bland variety of holiness as embodied in the Evangelical subculture. Close relatives include the Trad-Caths (“Traditional” Catholics) and the conservative Mormons. This entire crowd can be fairly characterized as believing that America works best when it’s a a majority Christian nation—with “Christian” defined in a pietistic/Calvinistic sense (with room left over for Catholics and others like them)—who live lives of quiet dignity and diligence and eschew hedonistic temptations. In the Trad-Con world, America is a moral exemplar to all nations, and will fall to dust if its moral purity is not maintained (at least in some measure).

The Neo-Cons are Trotskyists who came to believe that the way to accomplish the egalitarian and liberatory aims of Communist Revolution was to embrace the Free Market and spread it—by any means necessary—to the whole world. This is the “export democracy” crowd, the “strong-state conservatives,” and the “National Greatness conservatives.” They’re big believers in institutions, because institutions are where the power is, and what they want to accomplish takes a lot of power.

Separate and apart from both groups we find the “Neo-Trads,” who can be fairly characterized as wanting to turn the clock back to the 1990s. And who can blame them? The 90s were an apocalyptic decade, full of excitement and possibility, the latter-half propelled by the first tech boom, animated all through by the death of the Evil Empire and the emergence of Global Democracy. The extremes of hope and grief living side by side gave us fantastic popular arts (especially in music and film) that set a standard that’s yet-to-be-met in the mass market. Perhaps most importantly, this was the last time that the United States felt like a united country instead of a bunch of warring fiefdoms. We had bitter internal squabbles, but we were Americans, by God, and that meant something.

In their lust to re-capture this by-gone era, the Neo-Trads (and their fellow travelers among the disaffected liberals who aren’t all-the-way in their camp) are all reaching back for dependable dogmas:

The Nuremberg Code, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Chesterton’s Fence, and, with increasing regularity, religion in general and Christianity in particular.

Religion, they argue, is a uniting force. It’s where the real strength of a culture comes from. Their hope, as articulated recently by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, is that the deep history of Christianity can unite the West and save it from the current storm created by nihilism, consumerism, social media, Wokeness, and militant Islam. We need a moral core and center, and it doesn’t matter whether the core claims of Christianity are true or not, it only matters that we draw upon its power as a narrative in order to save our civilization.

So what is the Christian narrative?

That all may be saved. That all are of equal worth. That the Golden Rule is, in fact, the gold standard of morality. That meaning can be found in prayer and community and ritual much more readily than it can be found in partying or twitter or cancellation mobs. That abortion and birth control and sexual liberation are undesirable per se (and also at fault for the decline in the birth rate). That adherence to Christ’s teachings will roll back the cultural decay and spark renewal.

We see the beginning of the Neo-Trad movement in the 1970s-1990s, with the foundation of the Discovery Institute’s Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture, and with the founding of the Templeton Prize. In both cases, successful individuals worried—as many presciently did at the time, including Alan Bloom—that the West was in decline, and that if something wasn’t done about it, it would be curtains for our glorious civilization.

But after the events of September 11th, the Neo-Trad movement went more-or-less dormant…for a while.

Why The New Atheists Failed

The rise of the New Atheists can be laid at the feet of Sam Harris, whose book The End of Faith capitalized on and accelerated a mass defection-from-Christianity among Generation X and older Millennial Evangelicals. Building on this cadre’s bubbling resentment of Evangelical incoherence and hypocrisy on sex, sexuality, and charity towards the underclass, and supercharged by the visceral and visible example of the kind of thing that true, deep, and fervent faith can do—such as embolden suicide hijackers to crash airplanes into buildings—it became the first of several clarion calls to abandon religion in favor of “reason.”

Reason...as defined by a particular strain of late-20th century post-liberal thought. The moral vision of the New Atheists as championed by Harris, Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Penn Jillette, and many other less internationally prominent voices was one that accepted the received moral wisdom of the late 1990s as gospel truth. It is no coincidence that every single one of the New Atheist prophets was a former religious person (Harris was formerly a transcendentalist, Dennett grew up as a Methodist, Dawkins an Anglican, Hitchens a Trotskyist, Ali a Muslim, Jillette a New England Protestant, etc.). All, in a very important sense, remained religious throughout their lives because they held on to the moral certainty, universalism, and imperialistic ethos that has defined Christianity and its child-religions since the days of Tiberius.

The New Atheists, in other words, anathematized Christianity for being insufficiently Christian. Yes, some of them did offer critiques of the doctrines on the merits, but that kind of thing had been in common circulation in the West since before the days of Voltaire and Thomas Paine. What brought the fire to their movement was the moral certainty of the righteousness of their cause.

It should therefore be no surprise that the New Atheist movement was one of the early popular incubators of Wokeness per se.

Wokeness, in its uncritical championing of the outcast, its idolization of the victim, its worship of the downtrodden, its apocalyptic environmentalism, etc. is an extreme cartoon version of Christian morality and apocalyptic. Many of its intellectual antecedents—including Liberation Theology, the 60’s Civil Rights movement, the 19th Century Social Justice and Temperance movements, the White Man’s Burden, and the Global Missions movement—were explicitly Christian enterprises. All were forms of Christianity that sought the redemption of humankind through the exercise of righteousness and faithfulness through political power in the here-and-now. The Kingdom of Heaven was come with the incarnation of Christ, and it was the Church’s burden to carry its message and reality to all corners of the world.

The New Atheists were doomed from the start precisely because they were not the apostates they believed themselves to be. They never undertook what Nietzsche called “The Transvaluation of All Values,” which is to say they never re-appraised their value stack in light of their ostensible atheism. Without the Divine Command from the Divine Lawgiver sitting atop the teetering tower of moral rightness, universal egalitarianism cannot possibly make the slightest bit of sense.

Whistling Past the Graveyard

Here’s the ugly truth:

This is the end.

We are in the midst of a change in epochs. What historians call the end of a “secular cycle.” That means that several major historical trend-lines—all of which are foundational to our civilization—are converging on a nadir at the same time:

Economic debt load (both public and private)

Technological progress

Population curves (ratio of children and young adults vs. retirees)

Family integrity (the ability of small groups of people who are related by birth, marriage, or treaty to create power blocks that can serve as a basis for wealth creation and transmission)

Social cohesion (civic solidarity, national identity, social trust, etc.)

Ideological coherence (common value sets and mythologies that work in concert with one another)

When all the foundations of a civilization hit a long-term low at the same time, the civilization crashes.

Christianity, long in its decline, is not the vehicle that will save liberalism.

But that’s okay, because, despite what you may have heard, while the soil of Western civilization is partly fertilized by Greece and Christianity, Liberal western civilization depends upon neither and, in some senses, competes with both.

Liberal civilization—which is what most people mean when they now talk about “the West”—is characterized by:

formal equality (i.e. equality before the law)

individuality (i.e. the individual, not his family or group, is the unit to which responsibility is assigned)

pragmatic inequality (i.e. meritocracy which leads to different social ranks, wealth levels, etc.)

liberty (i.e. latitude to operate free from coercion)

the sanctity of private property (i.e. expropriation is a no-no, and theft is a serious offense)

the private right to violence in mutual combat, defense of self, defense of others, and defense of property

the sanctity of private life (i.e. sex and marriage and finance and inheritance are matters for the family, not for the government)

freedom of speech (i.e. you may say what you wish)

freedom of conscience (i.e. freedom of belief, religion and thought more generally)

the consent of the governed (i.e. if the people don’t like the government, they have the right to overthrow it)

In the above we can detect consilience with Christianity only in the principles of individuality and formal equality. This shouldn’t be a surprise.

Christianity has always been millenarian (i.e. focused on the perfection of faith in preparation for the End of Days), Platonist (devaluing of life in the temporal world in favor of the eternal), and communitarian (seeing all humans as equal before God—though some are more equal than others—and prizing the Communion of the Saints above all other things). We see these defining principles in the words attributed to Jesus and Paul and lurking behind the words attributed to James and John throughout the New Testament, as well as reflected in the records of the great early Christian synods and councils.

Christianity was to Rome very like what Wokeness is to the contemporary world. It was a package deal that exploited deep existing grievances, and was very good at playing language games. Like Wokeness, it infiltrated the Roman government to the point where it became the official state religion and helped accelerate the fall of Rome because it was, on nearly every point, diametrically opposed to the value system that built Rome and made it great.

The Church itself endured and survived the fall of Rome, and was able to take over as a sort-of seat of imperial governance (with its will enforced with carrots through financial favor, and with sticks through threat of hell and excommunication rather than through force of arms) because it found a way to contain its more radical values and impulses within the priesthood and the monasteries.

In this context, the social glue that the Church furnished through song and ritual, and in terms of practical ethical teaching, helped hold Europe roughly together. But we know that liberal society is not a child of Christianity because Christianity held nearly uncontested sway over most of Europe and the Slavic states and Asia Minor for over a thousand years, and in all of that time nothing resembling liberalism ever reared its head throughout most of Christendom.

Nor do any of Christianity’s child-religions, such as Islam, Communism, Fascism, Wokeness, Progressivism, or Liberationism, exhibit the slightest tendency towards liberal ways of thinking or doing things (except Mormonism, which emerged in the context of Liberalism). Instead, in all of these cases—as with Christendom itself—we see the official sanction of a very old and dark human impulse: the unrelenting lust to conquer the world on behalf of the community of faith, and then to purify the conquered until only those with the correct doctrines remain.

“So,” say the humanists, “why not look to the Greeks? It was the recovery of Greek thought that broke the back of Catholic authority in Europe, after all.”

Sounds good, until you actually read the work of the Greek philosophers. They were fantastic in matters of logic and argumentation, brilliant on matters of art and meaning, and they pretty-well figured out how to make democracy work and what its limits were. But they were not, in any sense, liberal. There is, for example, nothing in the surviving classical Greek playbook (with the exception of some scraps of argumentation from Solon) that would advance the emancipation of slaves or the equal rights of women or general equality before the law regardless of class.

Classical civilization did have ideas about liberty and private property, but their ethics were in no way favorable to freedom of speech or religion. Indeed, religion in the classical world was not a matter of belief as much as it was a matter of practice. It was the performance of the rituals, the giving of sacrifices, and the keeping of the festivals that built social trust—what you believed was strictly your own business. There was thus a freedom of conscience explicitly divorced from the freedom of religion.

Further, while it is true that pagan Rome and Greece were models for the United States’ Founding Fathers (while Christianity most explicitly was not), those principles that were adopted were not adopted wholesale. Instead, they were filtered through another lens, one that had already given birth to the liberal tradition long before the Romans ever swept across Europe.

Liberalism of the sort outlined at the beginning of this section was how tribal bands in pre-Feudal Europe governed themselves. Celts, Germans, Britons, Welsh, Cornish, and Norsemen staked out small territories and worked out commons and customs through councils, courts, and experience.

The English branch of this tradition is called the Common Law.

The German branch was extinguished in the wars preceding and succeeding the Reformation (Charlemagne didn’t help much either).

The Celts themselves were more-or-less exterminated by Julius Caesar, excepting some of their farther-flung outposts in Scotland and Ireland.

The Norsemen—despite their habit of going “viking” (that is, “raiding”)—were (at least from what we can tell) the most liberal of all, with women holding property and having equal rights to (though not always the same rights as) men, and with slavery being a very limited and uncommon institution in their ranks. They continued in this tradition of liberty long after the rest of Europe had become Feudal and had fallen under the sway of the Vatican. It is thus no coincidence that Amsterdam became the earliest bastion of liberal freedom and commerce in the years following Reformation.

This liberal tradition finds fellow-feeling with Christianity only insofar as Christianity is useful to reinforce its aims.

Liberalism, for example, works best in small communities where trust is a given—Christianity, in providing a common identity, helps Liberalism scale (as any common identity does).

For another good example, consider Calvinism’s Protestant work ethic. It is an adaptive strategy in an open economy, even though Calvinist moralism is, itself, ill-suited to life in a liberal polity. The Puritans who settled Massachusetts first went to Amsterdam because of this freedom of religion, but they quickly scarpered off to the New World because the liberality of the city was eroding their theocratic millenarian solidarity.

Similarly, Christianity’s notion of universal brotherhood (at least within the Communion of the Saints) rhymes well enough with Liberalism’s formal egalitarianism and individualism that the two can travel well together for quite a while...right up until Christianity’s more radical nature asserts itself, finds formal egalitarianism insufficient, and instead breaks out in calls for enforced equality.

Christianity (in its orthodox form) does not survive long in the crucible of liberalism, because freedom of thought and conscience and investigation splinters its singular doctrines into thousands of variants. It does not survive archaeological or historical or textual scrutiny because those who put the Bible and the Creeds together were not concerned with “truth” that accorded with the facts of the real world; they were instead concerned with preserving and solidifying their tradition and communion. Nor does it survive rapid, regular, technological advances and the wealth they bring. As C.S. Lewis complained in The Screwtape Letters: “Success knits a man to the world.” [emphasis added]

Christendom is, as the last century-and-a-half have shown, far more compatible with its daughter-religions in its basic aims (the moral purification and salvation of humanity, the pursuit of universal justice, the construction of a truly “good” society) and in its preferred means (state-enabled control over thought, association, art, sexuality, and conscience).

Therefore, when we speak of the Enlightenment, we are not talking about a universal current coursing through Europe. We’re talking instead about a particular cultural movement that prized individual conscience over state and ecclesiastical authority, and the power of commerce over the power of church, state, and the landed gentry. It took hold in those trading ports and posts where power was not already well-centralized. It flared up early-on in Paris, it spread to Venice and other city-states in Italy, but it really took hold in the North—the Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Bohemia, England, Scotland, and (to a much lesser extent) Ireland.

Further, it only took hold because the disaster of the Black Death thinned the population down enough to make the previous power structures unsustainable. The resulting economic boom breathed onto the embers of the old Celtic and Norse tribal cultures, reviving the Liberal tradition in a new and muscular fashion, allowing it to spread across the world by virtue of the printed page and common literacy, and on the decks of ships powered by the lateen sail.

But the battle between Liberalism and the Feudalism was never quite won. Liberalism only works in cultures that have the attitudinal infrastructure to support it. The more of the pins you knock out from beneath it, the more precarious liberal society becomes.

Knock out the pins?

Let’s say you start taxing income and inheritance, thus ending financial privacy and using the proceeds both to undermine meritocracy and remove the burden of charity from the community...

Or outlaw private violence and instead vest violence only in the hands of the state...

Or censor speech for the stability of the community...

Or redistribute status along groupish lines instead of as a reward for or consequence of individual merit...

Or allow government officials to seize private property without warrant or due process because it might have been involved in a crime...

Or compel medical treatments or confession of shibboleths in the name of public safety...

Or remove power from the localities where individual voices matter into distant marbled halls where only the wealthy can pay for a vote...

All of those things have been eroded over the past 150 years by Christian activists and their allies among those daughter religions to advance the Kingdom of God and the “common good.” It is only since the 1970s that we’ve seen the flavor of the bulk of that activism change from explicitly Christian to explicitly “Radical” (i.e. Marxist, Woke, etc.).

Liberal civilization came to exist because tribesmen and craftsmen and yeoman farmers could operate quite well in conditions of independence, because the local group could decide what was in its own best interests without regular interference from distant princes, and because society had enough trust (and mechanisms to enforce it) to lubricate the interactions between neighbors.

It grew because the freedom it offered allowed the adventurous to stretch their hands forth and risk much to create that which had not previously existed.

And it died because Christianity and its daughter religions could not abide the exercise of freedom by their neighbors, and so sought to use the power of the state to undermine, one after another, the pillars upon which Liberal civilization rested.

Building the Future

Liberalism is dead.

It’s been dead since at least World War 2.

It was on life-support long before that.

We live in a fascist world, where righteousness and commerce and law all rest within the purview of the all-powerful State, though some States are less totalitarian than others. In the United States the ghost of liberalism lives on, as it did in those tribal areas through the middle ages. I, for one, hope the embers still smolder well-enough that when history breathes on them the fire will light again.

The post-Enlightenment world is ending for the same reason that Rome (and all other great civilizations) ended: the success of the civilization robs life of meaningful struggle and replaces that struggle with meaningless difficulties and distractions. All civilizations fall, and they do so on predictable time scales. This world is five hundred years old (the typical length of regional complex civilizations), and the American experiment is nearing its 250th year (which is how long world powers generally last). We’re due.

But the post-Enlightenment world is also ending for the same reason that the Medieval world ended: global demography is crashing and there’s no way to stop it. Herein lies the germ of a great hope.

Over the next thirty years, half of the people alive right now in the United States will die from old age (as will ~70% of the population in the rest of the developed world). Until they are all gone, the replacement generations will (because of the debt burden and the elder care burden and the ease of technological comforts) continue to shrink. Our welfare states, premised upon the bargain that the young and poor will, through taxes, finance the retirement and medical care of the old and wealthy, will collapse, and with them most of the currencies and nation-states that back them.

And there’s not a damn thing we can do to stop it, because in the 1990s, when we could have done something, everyone was panicked about overpopulation (among other things).

That is, of course, not counting the percentage of the population that will be wiped out in the wars, and plagues, and famines that accompany those collapses (the beginnings of which we are seeing right now). What those numbers will be are impossible to guess.

That’s going to open up a lot of territory (both literally and metaphorically). There will, once again, be political, economic, and cultural room to grow. What matters now is what kind of world we build after it all crashes and burns.

Historically, it is the years after the great crises that have been the best in which to live. That is when the future is built, and that future will be shaped by who is left alive and what they value.

Based on demographic trends, the “who” will be the Americans and the people in developing countries.

The “what” is now in question. Unless you have direct access to the levers of power, this is where the action is when it comes to building the future (the technological infrastructure also has a lot to do with it—check out my recent Note for a deeper exploration of how that plays into the whole game).

Reaching back to the traditions of the past and plundering them for their wisdom is valuable, laudable, necessary, and, well, wise.

But the temptation to glorify and return to the imagined past—one in which Christianity was the guarantor of liberalism—while an understandable one when the future dries up, will not work. It can’t. Not only is Christianity (and its father-religion, Platonism) the ultimate culprit in the current cultural madness, not only is it one of the forces that have destroyed liberal civilization, it is now over two thousand years since the promised return of Christ. Its ideas and thought-forms, emerging from the pre-industrial Iron Age, are as unintelligible to modern ears as the Eleusinian Mysteries. Even modern Christians find it unintelligible (how many of them can recite the Nicene creed, or have read Augustine, or have wrestled with the thousands of pages of theology attempting to unravel the riddle of the Trinity?).

Christianity will doubtless survive the current madness in some form, just as it survived the fall of Rome and the Reformation and the Industrial Revolution, but in each of those cases the Christianity that emerged was very different—and much weaker—than the one that came before.

If Liberalism is your concern, Christian love won’t help you. The Aristocratic Virtues, instead, are where the action is:

Resilience, courage, magnanimity, integrity, adaptability, and strength are the virtues that build any civilization.

Add liberty, individual responsibility, disputation, and respect of property to that mix, and you have the building blocks for a liberal civilization.

Rescue or Rebuild?

No ideology, no matter how laudable, can save us from the historical tsunami now breaking over us. But ideology can shape what happens after. Liberalism is not an ideology for comfortable people; it is a bloody, contentious, conflict-centered ethic that depends upon the willingness of all parties to fight for their own interests in order to function. Modern economists say that Liberal societies have an ethic of “cooperate in order to compete,” but the transverse is more accurate (and more revealing):

The central ethic of a Liberal polity is “compete in order to cooperate.” Because of this, the Liberal way offers few opportunities for political entrepreneurs seeking to “uplift the downtrodden” or practice other forms of piety.

Liberalism is a game-theoretical schema, not a moral one. It did not liberate the oppressed by championing the downtrodden or uplifting the weak; it did so by arming the weak and giving the downtrodden the right to fight for their place in the world.

A world friendly to liberal values starts with arming the individual and empowering him to protect his own. It builds by individuals and families coming together in trade networks and communities to enrich themselves and one another. The intellectuals (both public and private) who value such a world would be well served to climb down from the moralistic heights and paint themselves with the mud of pragmatism. Idealism is a luxury that means fuck-all in a world that’s burning.

Thanks for joining me as I hash through the weirdnesses of our upside-down world. If you find this kind of thing stimulating, please share, comment, and consider supporting my project to inject a bit of vitality into our public discourse. You can find my other books (nonfiction and novels, both) at http://www.jdsawyer.net/book-list.

Wow! Marvelous, JD. There are so many people on Substack with major intellects—I know a few things and ‘feel’ many more, but never at this level of narrative integration. <Hum, what exactly does that mean?…Well, it sounds good!>

AS A CONFIRMED EPISCOPALIAN I RESEMBLE THAT FACT! (pardon mois, just tryin all caps for E A ffect.)

as a 64 yr old father of five and grandfather of ten i do worry.