“Free advice is seldom cheap.”

—The 59th Rule of Acquisition

It was in Phoenix that I first experienced hate, at least as an adult. In a huge convention center, at a sales conference, in the midst of getting what would turn out to be an invaluable sales education, and I found within myself a cold, horrible rage. Rage at the thousands of dollars I’d spent on training materials over the previous six years in my career as a salesman. Rage at the motivational speakers parading on the stage. Rage at the continual, mindless prattling and platitudes, the symbolic language that appeared to symbolize nothing, the paeans and preachments on the power of positive thinking, and the asinine alliteration all the authors alighted on as if by accident (sorry about that).

Here I was, attempting to learn how to become a better salesman, and all I was getting was a perpetual parade of derpy dip shits regaling me with rah-rah talk of wealth-within-reach that, as far as I could see, was utterly unrealistic.

And yet every single high-earner I knew seemed to be hooked on this pathetic pablum. I was pissed.

I’d had my fill. It was the last sales conference I attended for over a decade. The books from the conference were the last self-help materials I purchased for at least as long.

Which is ironic, given that I have, for the past decade and a half, been writing instructional books and running a podcast teaching writers how to get the most out of their creative drive.

So what gives?

The True Nature of Teaching

In most of these United States, if you wanted to get a teaching credential you’d need to complete a course in “education” which consists of training in administration (modern schooling has a lot of paperwork associated with it) and a raft of “theory,” which is typically a mixture of solid developmental psych, wildly speculative fad-based “Educational theory,” and an extra helping of “pedagogy” based on the work of Marxist revolutionary and doctrinaire social theorist Paulo Friere. You would then be obligated to spend some hours in a classroom as a “student teacher.”

For a profession that requires so much training, the results are...well, let’s be charitable and say “somewhat less than impressive.”

And yes, there are some pretty sinister and upsetting reasons for why teacher training is so useless (I delve into them in depth in my books Reclaiming Your Mind and The Art of Agency, both of which are due out later this year), but even if you were to set those aside, you run into a deeper problem:

Teaching isn’t easy.

A pre-packaged curriculum like you get in schools provides a lot of occasion for activity in the classroom, but it doesn’t do much to actually teach.

Teaching is another kind of art altogether.

“A school is a log with a teacher at one end and a pupil at the other.”

—Robert A. Heinlein, Rocket Ship Galileo

On the surface, it’s not all that difficult an art. Toddlers teach each other things all the time, after all. Whether you’re teaching carpentry or history, all you have to do to teach another person is to hand to them the tools and understanding you use every day. Easy peasy.

And if you’re wanting to learn? Well, thanks to the Internet you can find almost anything taught by people who really know what they’re up to. Advanced or unusual subjects (like languages, philosophical systems, etc.) present additional challenges, but nothing that can’t be overcome by a motivated student and a canny instructor.

So, all other things being equal, if you have something you want to learn, you should learn from the best expert you can find, right? Who wouldn’t want to learn investing from Warren Buffet, or physics from Albert Einstein, or sculpting from Michelangelo?

Consider the number of self-help and self-education books for people in your line of work. There’s no dearth of books on “How to be a success at X,” and they provide the supply for a bottomless demand for such advice and secrets.

But surely, if such books and their related courses worked, the people who consume them would show far higher rates of success (in whatever field) than they currently do, right? At least, assuming the books are making an earnest attempt to deliver value for money?

Well, kind-of. In the last few years, as I’ve been running The Every Day Novelist podcast and writing the aforementioned books, I’ve learned that there are some hidden obstacles to the transfer of knowledge. I submit them for your consideration so that, if you’re a student, you’ll get more value out of your studies—and, if you’re a teacher or mentor, you might be able to do your work more efficiently.

Motivation and Survivorship Bias

First, let’s get a couple common answers to “Why doesn’t self-help/business education work very well?” out of the way. Both are real phenomena, and not to be underestimated, but they are well known and they don’t account for the vast disconnect between aspiration and efficacy.

The first of these is student motivation. It is, in a real sense, impossible to teach anyone anything—the best one can hope to do is supply the opportunity and incentives for the student to learn. Learning is a natural human instinct. Yes, it is one that our civilization works hard to suppress, but it remains easily reactivate-able in even the most recalcitrant subject so long as the material taps into their interests.

Second, let’s consider the other popular scapegoat for the uselessness of expert advice (especially anything that purports to show the secrets to success): survivorship bias.

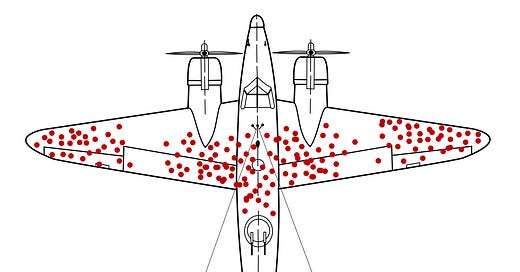

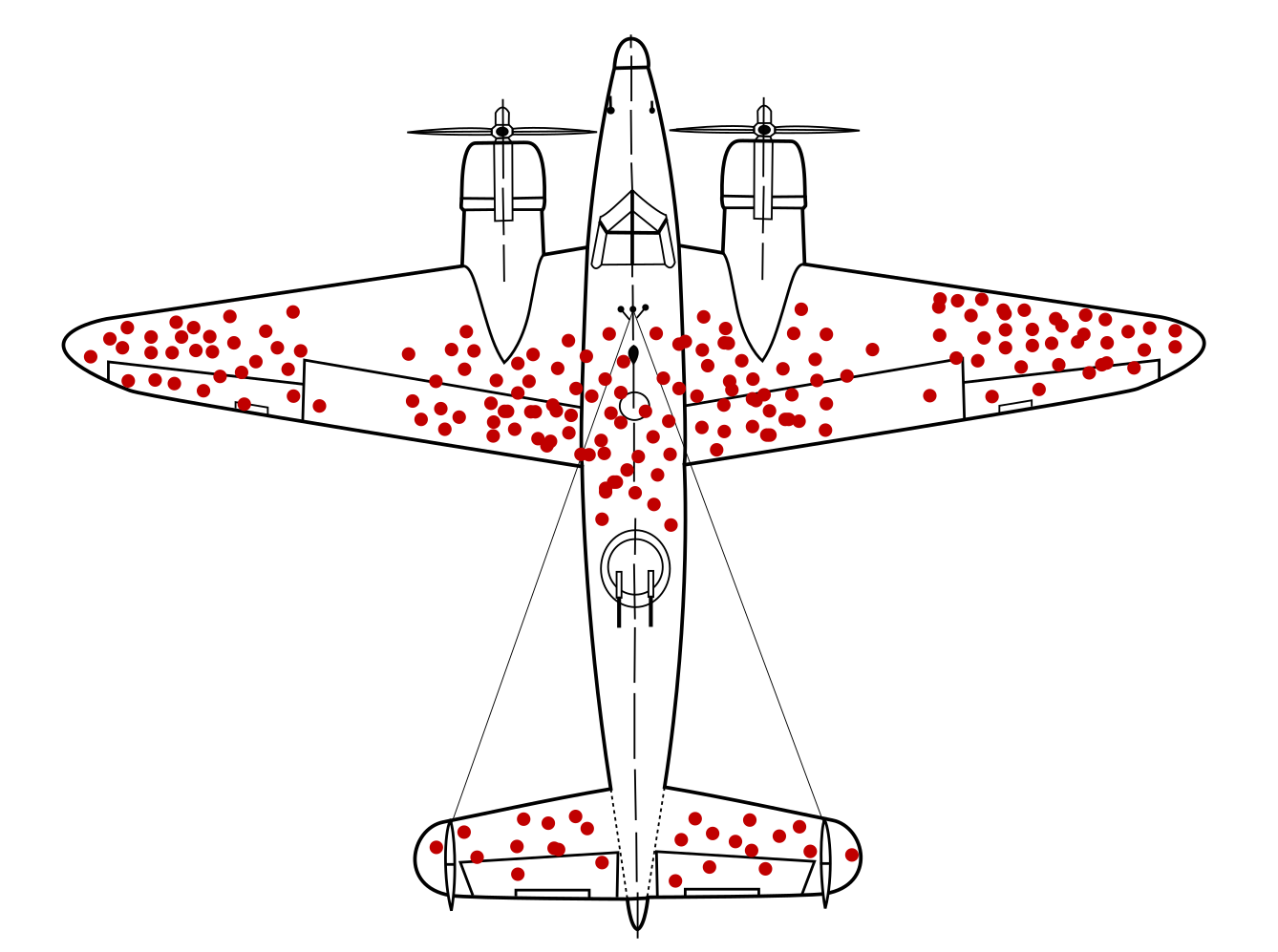

If you’ve been on the Internet for more than thirty or forty seconds, you’ve likely seen this picture:

This is an illustration of battle damage of Spitfire fighter planes that successfully returned to England after sorties flown during the second World War. The battle damage, so the story goes, told the engineers where they needed to reinforce the planes so that they’d be less likely to be short down. Alas, adding more armor to the planes where they were most likely to get shot didn’t seem to change the survival rates, and it reduced the range of the fighters (heavier planes = lower fuel efficiency).

What the British brass should have done (and what they eventually did) was look at what damage the returning planes didn’t have. The damage on surviving planes showed what damage a plane could survive (which seems obvious when you word it that way, but the pressures of war can create tunnel vision), while the damage they didn’t have—such as damage to the cockpit—showed what kinds of attacks these planes and their pilots could not survive.

This is survivorship bias in a nutshell. To model yourself after what you can see in successful people, and assume that this means you will succeed as a consequence.

It’s a flaw in reasoning because it ignores the embarrassments, setbacks, and other things that successful people might try to hide or ignore in order to burnish their image. It also doesn’t take account of disasters that they avoided (either by luck or skill). And, further, it might ignore hidden advantages—like a wealthy friends-and-family network that are willing to invest during crunch times—that the average Joe just doesn’t have access to.

Thus, among aficionados of survivorship bias, the prevailing attitude is:

“Don’t study successes for best practices. Study failures for worst practices. Avoid the worst practices, and you’ll be ahead of the curve.”

This is a domain-specific formulation of the scientific method—the kind of thing I tend to think is a pretty good idea.

But when it comes to learning, and particularly to actionable learning, it does leave a lot of gold on the table.

Fortunately, as I intimated earlier, the difficulty of successfully transmitting expertise is not chiefly a matter of either student motivation nor of survivorship bias. I have discovered (and I doubt I am the first to do so) a third axis that creates far, far more mischief than either of these—and, glory be, it can be worked around!

The Centipede’s Problem and the Hole in the Learning Map

A while back, I satisfied a lifelong ambition by learning to weld, and then learning the basics of blacksmithing.

When my two metalworking instructors took me under their wings, I noticed something odd:

Most of what they were telling me was pretty...well...useless.

Well, not exactly useless, but it was all the basic stuff that you can learn in five minutes from any introductory pamphlet or YouTube video (and that you can deduce if you know anything about metallurgy or electricity).

So I only listened to them with one ear. I put all the rest of my attention into watching what they did.

And what they did was not what they were telling me to do.

Over the course of their many years of experience, both teachers had learned how to do things well. But when they tried to teach, they only knew how to teach what they’d been taught. To be fair, some of the disconnect was of the “you must walk before you run” variety. Most of it, though, was because the “walk” instruction was actually wrong (or, at least, sub-optimal).

Here’s what really caught my attention:

With both my welding mentor and my smithing mentor, when I asked about one discrepancy or another, the instructors were not only shocked that they weren’t practicing what they preached, they immediately fumbled the next time they tried to do the action in question.

There is an old fable about a centipede and an ant, who came to be friends as they crossed paths every day while foraging for food. One day, as they ran into one another, the ant said to the centipede:

“I don’t mean to be rude, but I’ve been dying to know: With all those feet, how do you know which order to step in? Do you do the right side first, then the left side, or do you do right-left-right-left-right-left all down the line? Or do you do something else?”

The centipede pondered a moment, and then said:

“I’m not sure. I’d never really thought about it. Let’s find out.”

He then took a couple steps, and fell over.

The centipede was an expert at walking, but he did not know what he knew.

The same was true of my metalworking mentors. They were virtuosos in their craft...but they had no idea what they were doing.

Most Experts, Aren’t

Once upon a time, when it was the obligation of experts to have apprentices, this wasn’t a problem. Whether your trade was blacksmithing or bookkeeping, pottery or politics, earth-moving or entrepreneurship, your obligation as a master of your craft was to take proteges under your wing and train them up in the ways of your world.

The last century of subsidized schooling has destroyed that arrangement, breaking a tradition that is literally as old as the human species.

Now proteges are picked from graduates or promising undergrads at institutions that advertise themselves as training grounds for a particular trade. Masters in a given field—a title which exists to denote one’s suitability and readiness to take on apprentices—need not worry themselves about training up newbies anymore. All they have to do is hire help that’s already, effectively, at journeyman level in terms of basic knowledge.

Even in politics (one of the few professions that still practices a ghostly form of apprenticeship through its internship programs) one can see a near-total break in the continuity of knowledge in the past few generations. The subtleties and strategic depth of machine politics has been replaced with the outsourcing of such matters to statisticians, marketers, consultants, and other mandarins, leaving both campaigns and governance in the hands of poseurs who have no understanding whatever of the millennia old discipline of politics (which is both an art and a science).

This matters, because the purpose of apprenticeship is not to teach the apprentice what to do—that can be done by even the least competent instruction-manual writer. What the apprentice learns when sitting at the elbow of a master is why something is done, and how to think about the discipline in order to solve novel problems. It is the transfer of mastery, not merely knowledge, that allows any discipline to rapidly advance from generation to generation.

And that is what creates advances in human and material culture—what most people glibly denature with that question-begging and moralistic euphemism: progress.

Who Reads the Books

And this, I contend, is why such a slim portion of the readership benefits from self-help books of any kind:

The people who are able to take on the instruction contained within the books, for whatever reason, already embody or practice all those things that the authors do not know how to teach. These authors and mentors, experts though they are, genuinely don’t even know that what they’re good at is not the thing they’re teaching about. Like a woman attempting to teach a man what it’s like to be a woman (or vice versa), they do not have a frame of reference that allows them to map the disconnect between their mind and another that does not already think the way theirs does. They have no idea that their mind only thinks the way it does because of the expertise they’ve built.

Those few teachers who have made it their business to learn how to communicate the whys, and the how to thinks, and (even more rarely) the worldview components of their discipline are still carrying on that old apprenticeship tradition. Learning from them is a snap.

If you are a student, look for these people. If you’re a student in a discipline like the arts (especially writing) or business (especially sales), try to make it a practice to listen past the presentation. In fuzzy fields like these, even masters are often constrained by the language they have developed in order to explain their knowledge to themselves. You may have to learn their language in order to grasp their message.

If you are a mentor or a teacher, and wanting to become a better one, I recommend two strategies:

1) Attempt, always, to explain your methods and knowledge as if the student shares no frame of reference with you. Doing this, you will build with your student a common language which will make everything after much easier.

2) Make it part of your job, every day, to pay attention to what you do, and why you do it, and how you arrived at that “why.” Treat it as if the fate of the world depends on you being able to explain as much of the subconscious machinery, body memory, and embodied knowledge as possible. The better you understand what you’re doing, the better you’ll be able to pass on your best tricks and insights instead of just giving your student a place in the same starting blocks whee you began.

This post grew out of the final-phase edits of my upcoming book Reclaiming Your Mind: An Autodidact’s Bible, a guidebook to learning, thinking, and teaching based on nearly thirty years of experience training and mentoring others, and studying the way learning and apprenticeship have worked throughout history. Watch for it this July.

Thank you. I hope you are feeling better now.

re: "Watch for it this April" ... there's been a delay? or I am not watching for it in the correct places?