Welcome to this week’s Maker Mondy—on Wednesday! It’s fall here at the secret mountain hideaway, and that means that it’s “Quick! Get everything done before the ground freezes!” season. Fortunately, I can only lift so many heavy things before I need a break, so I was able to nibble my way through writing this week’s build post…just more slowly than usual.

This post is very image heavy. Your email client may choke on it. If it does, read the original at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com

Enjoy!

Several years ago when I was trying to figure out what it would take to build up a proper home site on bare land, I received the following advice from someone who’d done it before:

“Don’t even try it without a tractor.”

So, like a good apprentice, I set aside cash to buy a tractor.

Alas, the gods of Covid and bad fortune had other plans. The move to the secret hideaway wound up costing approximately two engines and a transmission in the Designated Homesteading Vehicles, which pretty much wiped out the tractor budget.

But time waits for no Dan. Firmly ensconced within middle age, I have only so many years before I must work with heavy machinery and hirelings to get anything done, so if I wanted to be able to put up all the support buildings I’d need to actually even attempt a home build, I couldn’t wait around for the right tractor deal and cash pile to materialize in this uncertain economy.

The area I live in was first pioneered by people with their bodies and hand tools—sometimes they didn’t even have horses to supply the, well, horsepower. Some of the buildings they built are still standing fifteen or more decades later.

If they could do it, I figured, so could I…

…I hoped.

My homesteading partner and I both recently got downsized. To keep the dream alive, we are currently seeking gigs for editorial, layout/design, voice over, audiobook narration, and strategic consulting work. Additionally, if you’re looking for a tutor for a student struggling with history, English, creative writing, or psychology, I’m available for hire.

Or you can help out substantially by joining me here as a paid subscriber.

The Logs of Physics (or Vice Versa)

In a forest that’s not been managed in seventy years and thus is in a constant state of high fire danger, logs are cheap: you get them for the price of walking into the forest and doing what the US Forest Service begs you to do in their regular mailings: thin out the trees that are tightly packed enough to be an Ent mosh pit.

Knock ‘em down, cut the limbs off,1 you got a log that you can then drag out of harm’s way.

Logs—even the thin logs you might use for roundwood construction—are heavy when they’re first cut. A 6-inch diameter, 12-foot long log can weigh up to four hundred pounds when fresh, depending on the species of tree and the season.

Why do I pick that size? Well, it’s the right length and thickness for sinking in the ground as a vertical anchor for pole-barn style construction, which is the cheapest ultra-sturdy way to build small farm buildings.

On the upside, if you leave a 6-inch, 12ft log out in the weather for a couple years around here, the dry climate will slim it down to around 80lbs due to moisture loss, which is a weight that a reasonably healthy man of average size can carry on his shoulder if he gets the balance right.

But doing that requires that you wait a couple years between felling and using a piece of timber.

And I hate waiting.

Now, moving heavy things without motorized machinery is nothing new to me. I worked warehouse jobs to put myself through college, and I was once an avid rock climber and treehouse builder. I’ve used rigging, hand trucks, dollies, pallet jacks, levers, rollers, and anything else I can get my mitts on to trick gravity into looking the other way.

Logs—even incredibly heavy logs—are really easy to move. They’re round. They roll. They work like really wide wheels, and even heavy wheels are pretty easy to move if you approach them the right way.

At least, when you’re moving over relatively even/flat ground.

And when you’ve got a wide enough path.

Moving a fresh log onto the saw mill is as easy as looping a rope around it and rolling it up a ramp on to the track where you can then turn it into lumber.

But if you’ve got a 12 or 20ft log (the two lengths I’m working with for my current build projects), and your logging trail looks like this…

…you’ve got to drag2 the thing. Which means you have to overcome all that friction from all the surface area of the log scraping along the ground. A 400lb log can require a ton or more of pulling force to move that way.

So how do you get around it?

When you’re moving something heavy like this, leverage and inertia are the two major physics principles at play. So you can either:

Find a way to reduce friction

Find a way to increase leverage, or3

Some combination of 1 and 2

For my first attempt to solve the problem of log hauling without a tractor, I opted for solution #2.

A come-along is a hand-operated ratcheting winch4 with hooks at either end. This one is rated for four tons. Hook one end around a tree, and hook the other to a twitch chain,5 and you can haul a hell of a log up hill, but it can take hours to move a log a hundred yards up hill. It’s miserable work, and frustrating. I gave it up after clearing one grove of four logs.

I needed a better solution, and I was at a loss.

Until…

An Unexpected Education

…I was informed by my wily homesteading partner that she had a tome packed with great secrets passed down from the homestaders of yore, and that within the pages of this grimoire might lie the sorcery I sought.

The interesting part of the book, in this case, was not the text—which on this topic merely explains what I just laid out above about friction and leverage—but the illustrations, which sketch out dozens of weird inventions that people have come up with over the centuries for lifting and moving heavy things. Things from A-frames, to Gin poles, to flip-flop winches, to treadmills and cranes and human hamster wheels, it details a dizzying array of ways that humans have discovered to win the war against friction and gravity.

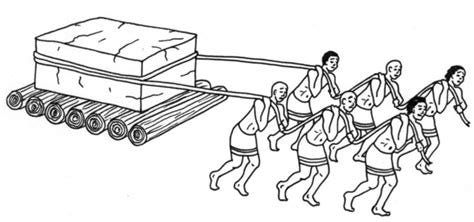

In my situation, the most attractive thing were rollers. Essentially small logs, the ancient Egyptians used these to move large stone blocks up ramps to build the pyramids.

But that presented a problem:

The ground I’m working with is way too uneven, both in surface texture and in firmness. Rollers are likely to get stuck in rabbit holes or on spiky rocks (I’ve got a lot of both).

What I needed was something like a cart—I actually tried using a cart, loading it by tipping it on its side and rolling the whole load on it, then tying the log on with ratchet straps.

It worked a treat, but the weight of the log just about broke the cart. Since it’s a vital piece of equipment around here, I didn’t fancy having to re-fabricate it.

So how to adopt the cart idea? I needed something I could grab logs with, lift them, and haul them that would at least get rid of most of the friction.

The book, it turned out, had just such an animal…

The Log Arch

A log arch is…well, a wheeled arch for pulling logs. Turns out they’ve been around for a few thousand years, and they’re still on the market today. The’re made in all sizes, designed to be pulled by tractors, trucks, ATVs, horses, and ride-on lawnmowers. Here’s an example for ATVs, produced by LogRite.

That looked to me like something I could adapt for human-power, using materials I had on hand.

The Design

The first stage of any build is the design. Unfortunately, I did this in chalk on the top of the welding table, and I didn’t take pictures (so I can’t share them with you), but I broke the project down roughly into pieces:

Hubs. I needed something to mount some wheels to.

Wheels. This was the one thing I would have to buy, as all the wheels I had on hand were way to small (the ones I wound up buying, honestly, were still too small, but they were what I could afford and they work well enough).

The outer arch. This would provide the frame stiffness for the entire thing.

The inner arch. This would provide flexibility and absorb shock, so that the outer frame wouldn’t twist out of shape if I overloaded the thing.

The grapple. A log grapple is essentially a pair of heavy calipers with upturned spikes on the end, which dig into the logs and grab them.

The lever. I needed a long handle that would give me the leverage to lift up logs from the ground, and that had a wide enough handle that I could really throw my weight into it.

The Hub Assembly

For the wheel hubs, I fortunately had some virgin materials around—plate steel fresh from the factory, left over from an earlier build.

The wheels I bought had their own bearings built in, so for the hubs I basically just needed axle housings. I burned up a hole saw cutting the holes for the bar stock that would comprise the axles…

I then fit up the pieces and welded them together, and inserted and secured the bars that would serve as the axles.

Then, to complete the hub assembly, I welded those onto the back plates, and added some gussets, so that the whole thing would support the weight that I was about to load it with.

The Log Grapple

The arch wouldn’t be much use if it didn’t have the ability to lift a log. For this bit, there were basically two choices: a winch, and a grapple.

I didn’t have a winch handy, and couldn’t afford one, but I did have some good round bar that my beginner forging skills might just be able to make into a grapple. The trick? Getting the two sides to match. Since it was a multi-step process, I decided to forge the two in parallel, making sure they were more-or-less identical every step of the way.

Now I had to put the frame together, and there…well, I had some interesting choices to make.

Off To the Scrap Pile!

All things being equal, I'd want to build the frame out of some heavy-duty square tube, but I didn’t have any on hand. The best I could do was some 1 inch round tube (what normies call “pipe,” even when it’s not used to, you know, pipe things from one place to another). I had a mess of this stuff that I keep around to use for cheater-bars when working on cars, but there was enough that I could get away with sacrificing some of it.

For the inner arch, I repurposed some leaf springs from an old and long dead Ford Ranger.

All that was left was to clean it up, weld the hubs on, and then get a handle together.

The Results

After adding a handle made from cross-members from an old trundle bed frame, I put the thing into service. Wonder of wonders, it worked!

I can’t say there aren’t things I wouldn’t change. Adding a rear axle that I can slide under the log would make a huge difference in how much effort it took to pull a given amount of weight, but I think that’s a project for next year. This year, the thing has acquitted itself admirably, pulling over a dozen logs out of the deep forest to go into service on the homestead.

Having to turn myself into a tractor instead of buying one certainly isn’t my favorite thing in the world, but it does make sights like this most satisfying indeed:

With any luck, my shop tent will be a proper shop by next spring, all thanks to this silly contraption pulled from a scrapyard, with a design lifted the pages of history.

If you’re looking for fresh stories, you can find my novels, short stories, visions, and dreams (along with some how-to books and literary studies) by clicking here.

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. If you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

This column is a big part of how I make my living—bigger now due to recent exciting events which you can read about here. Because of this, I’m offering a 20% lifetime discount off the annual subscription rate. If you’re finding these articles valuable, I’d be honored to have you join the ranks of my supporters!

For those of you interested in forest management, this is a delicate balancing act. The wood that gets taken out of the forest also removes nutrients, so bringing ashes and other decomposition material back into the forest is important for the forest’s long-term health (as measured in centuries). The limbs are a tinder source (i.e. once dry, they can be set alight by a stray spark and amplify the fire very quickly) so they either get buried, piled in a clearing away from other fuel sources, taken away to be burned, or used for smaller craft and construction projects, depending on the needs of the moment.

The technical term is “skidding,” for obvious reasons, but trust me, it’s really a drag.

And a winch, after all, is just a lever that goes all the way around in a circle.

The end of a chain secured around a log with a choker set up, much like a choke chain on a dog. Turns out that, just like all us mammals, Ents would also rather move than be choked.