I was five years old, and I was playing hide-and-seek. It was, as near as I can remember, a Sunday afternoon in the spring or early summer. I found a perfect hiding spot in the living room—I was just small enough to hide behind the high-backed couch.

The radio was on to NPR, a music show was just wrapping up as I secreted myself away.

A moment later, an astonishing sound blasted forth from the speakers:

Star Wars—which was the biggest thing in the world at the time—blared from the speakers. I’d only been able to see the movie on the little 16mm home theater edit at the time, but the moment was fast-approaching when I’d see it on the big screen in all its glory, in a double-feature with The Empire Strikes Back.

But this was something different: a radio drama.

I’d never even imagined that mere sound could paint a film more vividly than anything on the big screen.

I stayed behind that couch for the whole episode. I completely forgot the game. My parents actually went out into the neighborhood trying to figure out where I’d gone. I didn’t notice, and I didn’t care. I was entranced.

And I became obsessed.

Over the course of my childhood, I stayed up late to record radio dramas from late-night shows like Classic Radio Theater, When Radio Was, and (later on) newer fare from Jim French’s Imagination Theater. I gleefully hung on every sound that emerged from my computer’s tinny speakers with the SciFi Channel’s Seeing Ear Theater.

What’s more, I produced my own. Starting in junior high with a shitty Realistic (TM) omnidirectional microphone from Radio Shack (which I picked up for fifty cents at a garage sale), moving on to comedy sketches for the short-lived early Internet phenom Blenderwars and the half-hour long, gloriously tacky Beavis and Butthead vs. Darth Vader, I ate, slept, and breathed radio dramas whenever I could manage. I was the guy who had a hundred tapes in his car—ten of them music mix tapes, the other ninety filled with hours upon hours of Dimension X, X Minus One, Box 13, and so many others it would be tiresome1 to list them all here.

And, of course, when I got into podcasting, I just had to do full-cast, full-production audio fiction.2

All of which is to say that I love radio, audio fiction, and anything like it.

I love it so much, that I’ve produced several dozen audiobooks, radio dramas, and similar pieces—and wrote the book on how to do it.

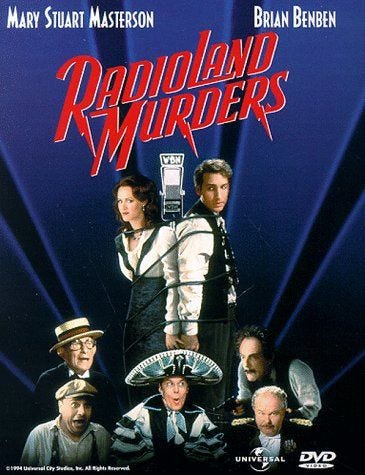

Which is why, when I rented Radioland Murders (back in the days of videotape), I was cagey. The gimmick of a murder mystery set in a 1930s radio station hooked me, but gimmicky films so often use their premises as mere veneers to tell modern stories. It was probably gonna suck.

Then the opening credits rolled, and I could barely believe what I saw.

Radioland Murders

If you’ve ever seen a Neil Simon play, a three-door farce, the film version of Clue, or classic movies such as His Girl Friday or Arsenic and Old Lace, you’re familiar with the genre of screwball comedy. It’s a high-energy, antics-laden genre of madcap farce where everyone is a bit like a cartoon character and all the action is treated very seriously…even though it’s so utterly insane that no real human would put up with it for a hot second.

Radioland Murders is that kind of movie. It opens on a high-energy walk-n-talk between a scriptwriter named Roger (played as a Groucho Marx tribute by actor Brian Benben) and his estranged wife, the station’s stage manager Penny (played with aplomb and wit by Mary Stuart Masterson). As they banter caustically through the halls to a double-time tom-tom track reminiscent of the intro to Benny Goodman’s Sing Sing Sing, we’re treated to rapid cuts of a life behind the scenes on the eve of the premier of a new radio network in the 1930s:

Costume rooms, page boys, sponsors and schmoozing, the seating of the live studio audience, and, most delightfully, the Foley artist giving his bag of tricks a dry run.

The technical aspects of this world unfold as a glorious story all their own—how the mix works, how the sound effects are made, how the actors switch voices and play scenes. Like a Penn & Teller routine, when you see how the magic trick is done you’re left more amazed, because you can’t believe something so boring and obvious could actually work.

As the opening credits roll under a fantastic musical number (the first of over a dozen), every frame packed with storytelling and spectacle—so much that, on a first viewing, you might miss the fact that the entire film is set up during these first few minutes. Every relationship, all the geography, every important fact, and even the identity of the murderer is set up by the time the opening credits wrap with the first murder.

And before I go on, I have to mention another thing about the credits.

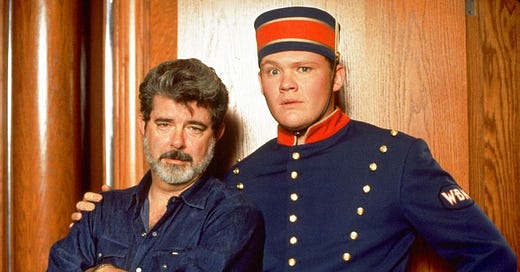

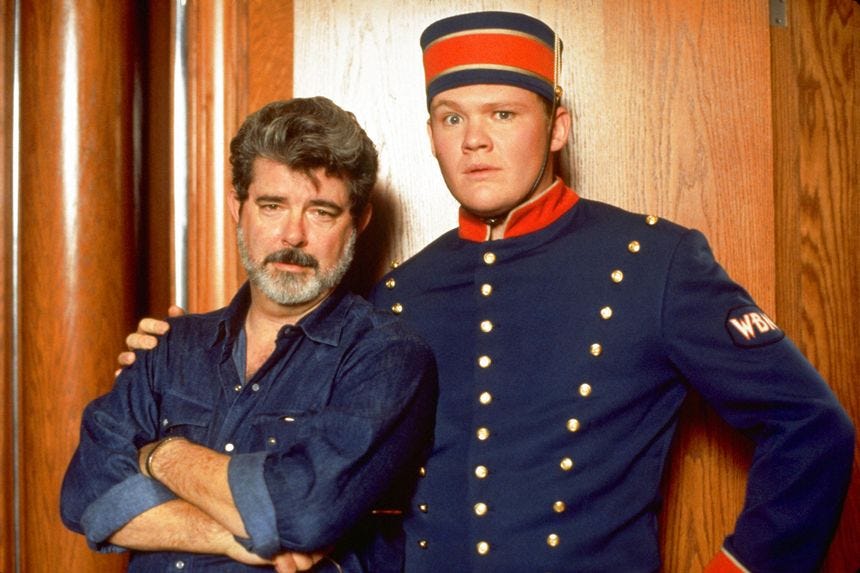

This is a George Lucas film—conceived by him as a tribute to the golden age of Radio in the same way that he originally conceived Star Wars and Indiana Jones as tributes to the Flash Gordon and adventure serials of his youth. It’s written by the husband-wife team of William Huyck and Gloria Katz, who also wrote the screenplays for American Graffiti and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.3

Its cast list is nearly endless, populated with golden-age talent like George Burns, Rosemary Clooney, then-upcoming voices like Harry Connick, Jr. and Jeffery Tambor, and a ridiculous lineup of perennial talent: Christopher Lloyd, Michael McKean, Michael Lerner, Ned Beatty, Stephen Tobolowsky, Bobcat Goldwaith, Harvey Korman and Dylan Baker (and that’s just for starters).

They all bring their A-game, which is good, because in a script this fast-paced, intense, and filled with gags, a single false note would blare forth like a fart in church.

And it’s not as if there isn’t rampant opportunity for false notes. There’s a quick one-liner jab every few seconds, complicated chase scenes involving catwalks and neon signs, accidental drag acts and femme fatales, fake adultery and real betrayal, bathtub gin and bi-plane shoot-outs, all set in-and-around tribute scenes each meant to be reminiscent of some of the greatest radio shows and variety acts of all time (many of which turned into TV shows later on).

The screenwriters go on strike, the head writer gets framed for murder, a ghostly voice haunts the studio, and there’s a running thread about a toupee that seems to want to do anything to escape its owner’s pretentious noggin. Poisoned gin, electrified mic stands, laughing gas, giant crushing machines, elevator shafts, and machine guns all claim victims as a tale of industrial intrigue and espionage unfolds under the noses of the performers, the pursuers, the burlesque primadonna’s peccadilloes, and the policemen’s paltry brain cells.

In this kind of breathless farce, the slightest misstep would make the whole complicated jitterbug dance come crashing down.

But no misstep ever comes. The central story is bursting with heart and heat and irony, and all the many, many sub-plots keep things hopping and interesting even through the show’s few fallow moments.

Oh, and the whole thing was directed by British comedian Mel Smith, who you might recognize:

Excellence and Fun

There are two kinds of period pieces:

Those that dress modern characters up in archaic costumes

Those that show you the alien world of the past on its own terms

Radioland Murders fits firmly in the latter category, and it does so with glee, finesse, affection, nostalgia, and more than a bit of dry wit. It’s a rare thing for a comedy to remain fresh after multiple viewings, but the early 90s were a golden age for this kind of masterpiece,4 and Radioland Murders fits right in.

That is nearly the definition of “excellence in craft.”

During this year’s long-dark (the five weeks on either side of the winter solstice, during which northern latitudes get very little sunlight), I dusted off my copy and watched it for a mood lifter. It still works.

For those of you who’ve never experienced the lost art of the radio drama, this film likewise makes a fantastic introduction—you’ll even learn a bit about the performing arts, as many of the behind-the-scenes tricks-of-the-trade on display are still in use in film, theater, live music, and audiobook production. And for those of you who, like me, harbor a secret (or not-so-secret) affection for this archaic artform in all its glorious guises, the sheer immersion factor of this film will keep you smiling from beginning to end—and, on repeat viewings, you’ll find yourself straining to hear new fragments of the radio shows that constantly soundtrack the film’s background from opening number to closing curtain.

So next time you’re looking for a high-energy pick-me-up, give yourself a treat: spend the evening of pure, unmitigated joy at a 1930s radio station, and solve a half dozen murders while you’re there.

You can find some of my work in the audio arts on my podcasting page (click here)—enough of it to fill your entire spring with narrative delights. If you’re looking for other tales to transfix your imagination, you can find my novels, short stories, visions, and dreams (along with some how-to books and literary studies) by clicking here.

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books.

This column is a big part of how I make my living—bigger now due to recent exciting events which you can read about here. Because of this, I’m offering a 20% lifetime discount off the annual subscription rate. If you’re finding these articles valuable, I’d be honored to have you join the ranks of my supporters!

Okay, more tiresome.

My podcasts you can find here. For Gail Carriger’s Crudrat—a Heinlein-style Juvenile by the steampunk romance author of The Parasol Protectorate series, click here.

And, also, Howard the Duck

See also: Oscar, Undercover Blues, My Cousin Vinny, The Ref, What About Bob?, Wayne’s World, Clerks, City Slickers, White Men Can’t Jump, and Groundhog Day, all released within three years of Radioland Murders, and all also nearly infinitely re-watchable. Something funny must have infiltrated the early 90s Hollywood cocaine supply.