The Metaphors We’re Made Of

Reconnecting to History, part 3

“Why is he limping?”

“His feet are the wrong size for his shoes.”

—Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Fit the Eleventh

Human Nature in a Smart Phone

Confession time: My twitter habit is a problem for me—and not for the normal reason. It doesn’t eat my life, I don’t get lost in doomscrolling, and my family hasn’t threatened to disown me for bringing them into ill repute. It’s a problem because I’m a professional writer and, most of the time, I post from my phone.

The cascade of crap that is my typo-ridden tweet stream is a thing of unusual and startling ugliness, and it’s not even my fault; it’s my phone. It’s too small for my fingers. Without the tactile buttons that used to be present on phone keyboards, I can’t locate the keys by touch—and, most of the time I’m typing on my phone, I’m not in lighting conditions where I can easily check for typos (i.e. I’m outside, which is where I spend most of my time). Modern smart phones are not built for people like me—neither people of my physical size (imposing) nor of my lifestyle (which involves a lot of daylight, and daylight makes the screen hard to read even on the brightest setting).

One time in my life I found a phone that fit me, and that I could afford. I held onto it for twelve years—I still have it, in fact, even though a frequency shift means that it won’t pick up cell signal anymore. I live in the faint hope that one day my electronics skills will grow to the point where I can retrofit it for the current frequency bands.

Our world is like this. Despite the massive variety of consumer “choice,” we all bump up against the limitations of one-size-fits-all thinking. It’s annoying, and, more annoying still, it’s not something our great-grandparents (or great-great grandparents, depending on your age) had to deal with much of. It is a by-product of the industrial age.

But we live in a post-industrial age now. Manufacturing is flexible, and we can print-things-on-demand. We shouldn’t be dealing with this crap anymore, should we?

Ideally, no, we shouldn’t, but we are, and if we peer deep into history, we can see the reason.

Our technology, you see, has a profound influence on how we think about life, the universe, the gods, morality, and, well...everything.

The Fact in the Fictions

History, to make sense to us, has to be put together as a narrative. Invariably, that means that we will eventually come into contact with ways of thinking that are strange to us. Why did so many cultures practice blood sacrifice? How could they have advocated child-beating? How could people in the past have thought the world was flat, when you can clearly see the curvature of the horizon if you’re on a large enough, flat enough space? Why did they think about sex and marriage and religion differently than we do?

The fairly obvious reason for all of this is that they understood the world—and humanity—in different terms than we do.

Okay, then, so why do we understand these things the way we do?

Believe it or not, and despite the fact that there are many factors at play, we understand these things the way we do because of the technology we use to master the world. Our day-to-day experience of technology shapes our expectations of everything, and it does so whether we want it to or not.

The World of Cattle and Bronze

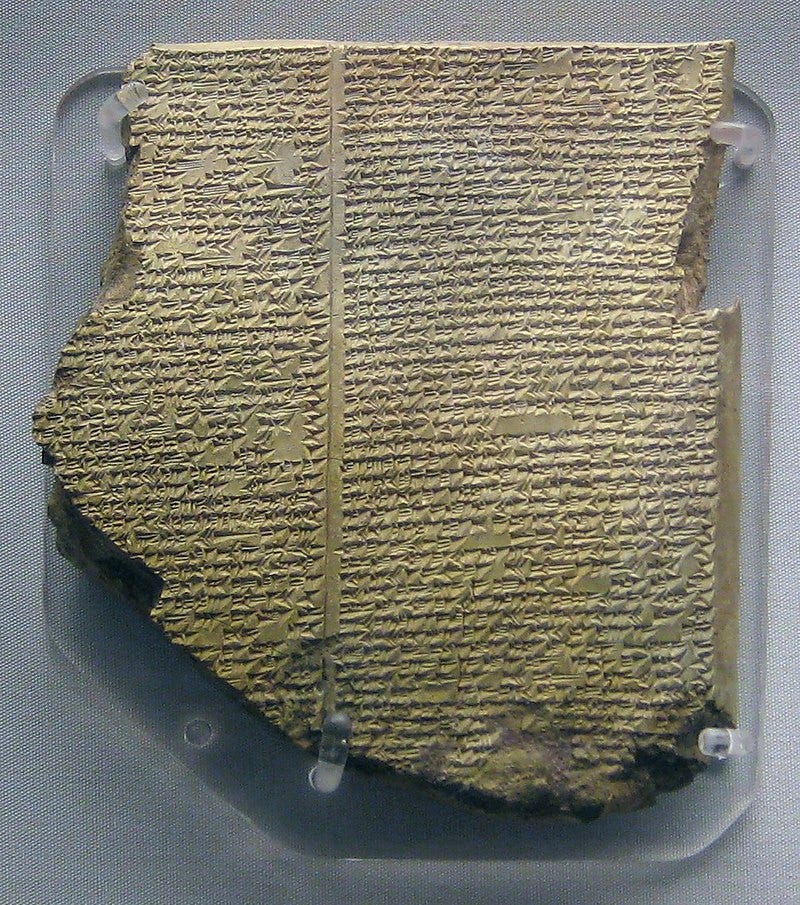

Our civilization begins in the Bronze Age: the Greek and Sumerian and Babylonian epics (The Illiad and The Odyssey, The Enuma Elish, and The Epic of Gilgamesh, respectively) and the Hebrew epics that were inspired by and/or based upon and/or shaped by these epics (the biblical books of Genesis, Exodus, Ruth, The Song of Songs, Job, Esther, and large swaths of Judges) all date from this time. It was a time of rapid change from the life of the nomadic herder to the settled civilization, and all of the above epics deal with one aspect or another of this transition and its effects.

The development of bronze (an alloy of copper and tin) was vital to this transition, and as cities formed, settled agriculture became more important. These two technologies, and their relationships with each other, shaped literally everything about how the Bronze Age peoples understood their world, and themselves.

Settled agriculture created formal land ownership, and the farms fed the cities. Since the cultural group was too large to move if there was a drought or the game migrated, the viability of the civilization was dependent upon the fertility of a small patch of land and the loyalty of one’s fellows to the common survival and fertility project. The natural rhythms of planting and harvest, fertile times and fallow, feast and famine came to dominate the way the ancients thought about everything:

Fertility cults and festivals (and their attendant orgies and ritual prostitution) were part of the fabric of life

Even wars followed the agricultural rhythm: they were often fiercest during the off-season when farmers weren’t needed in the fields

Farmers learned the value of delayed gratification—today’s planting is next year’s bounty.

The weather could ruin you, so it made sense to sacrifice to the gods—and you could figure out how much you owed them for your sins by using a new notion: “proportionate justice.”

On the open range, where clans fought over pastures, vendetta-based justice was the only way to stay safe. But the cities changed this game. Just as the soil responded in kind to the deeds of farmers, so too people were expected to respond in kind to the deeds of one another. “We all have to live together,” the reasoning goes, “we are locked in a dependent cycle. We cannot simply ruin someone because they have done a small wrong. The loss of an eye only merits only as much revenge as the loss of another eye in turn.” This sense of proportionality was written into the Code of Hammurabi, which, in all its rules, ruthlessly co-located agency and responsibility.

While Bronze Age moral and legal systems were harsh, they weren’t inflexible. Instead, they were highly pragmatic and (to modern eyes) un-ideological. Good character was marked by flexibility as one would expect from a culture formed around the other great technology of the time:

Bronze.

Bronze is easily manufactured from raw ore over an open fire (with the use of a bellows). It is a soft, resilient metal that takes an incredibly sharp edge on tools that are remarkably durable and versatile, especially when compared against stone-age technologies like pottery. To that point, it was the most versatile material the world had ever seen. And, importantly, it doesn’t have to be purified in order to embody all the best qualities of bronze.

The soft metal quickly lost its cutting edges, but it re-sharpened easily. You could pour bronze into a shape, and it would take the shape given, but with use those shapes would adapt themselves to the tasks at hand. Mechanical bronze computers were built to aid navigation and predict the movements of the heavens. Bronze blades harvested wheat, slaughtered livestock, and defended the homeland.

Child-rearing philosophy of the age reflected the nature of bronze. The job of the parent was:

Casting the child in the proper shape

Sharpening his mind

Teaching him to dull destructive appetites

Shaping his will for the task at hand

Bending (but not breaking) his nature to submission to the group.

Bronze Age cultures had soft sins and easy redemption. Just as one can easily clean a dirty bronze tool with washing, and restore a bronze knife-edge with a bit of honing, so too could one easily wash away sins with ritual purification in water and blood, re-sharpening the moral sense with proportional justice. Even that most apparently abhorrent of categories, abomination, was a kind of ritual impurity, not a hopeless and permanent stain upon one’s character.1

The properties of bronze functioned well as a metaphor for everything from the health of a human mind to the structure of the universe—the blue sky was the color of an oxidized bronze bowl, so the dome of the heavens was seen as a bowl covering the earth.

As Iron Sharpens Iron

Pretty wild, eh? Feels almost primitive, doesn’t it? Thank God our understanding of the world isn’t a big pile of analogies!

Well, not so fast. Let’s take a look at the world of Iron (Rome and Europe) that succeeded the world of Bronze (Babylon, Greece, and Egypt).

Iron is harder to find, more expensive and difficult to smelt, and its alloys (like steel) trickier to formulate. Where bronze can tolerate impurities and oxidization enhances its ability to endure, oxygen corrodes steel (rust) and impurities ruin it. Yet steel and iron are stronger than bronze: they’re less bendable, they’re harder, and they melt at such a high temperature that they can’t be easily cast (especially with ancient technology)—instead, they must be forged. In other words, the metal must be heated up to a glow, then hammered, bent, and pressed into shape. It’s a huge pain in the ass. Trust me on this one, I forge things all the time in my smithy. It’s an amazing amount of work, and very delicate, since it’s easy to “cook” the steel, whereupon it disintegrates.

When all good things are made from iron, the properties of iron become the properties of goodness. Stalwartness, permanence, and purity are presumptive goods, because good, dependable steel lasts nearly forever, but only if the alloy is pure.

Since flexible iron is weak, and can’t be easily repaired if it bends under stress, moral rigidity is prized above flexibility—and moral character is forged by taking a beating at the hands of one’s instructors.

The Iron Age empires had urban life on a scale the Bronze Age couldn’t have dreamed of. This separated the urban centers by sometimes hundreds of miles from the farms that fed it, which, in turn, completely changed the way that manners and morals worked.

In the city, one must be predictable to strangers, not just to friends. Since one must interact with people who do not know one’s character, one must have character traits that are easily seen. Straight posture, an iron will, an untarnished reputation, strength, and an unwillingness to bend under pressure all—like iron itself—became markers of trustworthiness.

And, because so much of the population in these empires was urban, the people no longer saw dung and blood and sweat become food and wealth and plenty before their very eyes as if by magic. The transformations they could see—those that happen at the smithy and the water-driven mills and even in the kitchens—are no longer gentle and natural, but extreme and artificial. Fire, not growth, purifies. One’s rough edges must not be polished through continuous use, but ground down aggressively.

In this world, a moral failure is categorical—the twisted blade cannot be made straight again without destroying and re-forming it. So, naturally, humans with moral failings must be un-made and then born again. Routine ritual purification fell out of fashion in favor of religions of categorical redemption and damnation—sometimes cyclically, but always total and totalizing, rather like the authority of the iron-age state, now made total by the scarcity of iron and the invulnerability of steel weapons and armor to anything not also made of steel.

Loyalty to people, indispensable in an earlier world, becomes intolerable in an iron age world. Loyalty to ideologies and systems and abstractions (like “the State” and “the Church”) are, instead, the yardstick of morality. Everyone loves and fears for their children; it takes a truly moral person to love and fear his ruler, city, and gods even more than he loves and fears for his children.

And lets not forget what iron and the maritime empires it enabled did to the heavens; instead of a copper bowl holding humanity in, the skies become a sea that might be sailed.2

Endless Lenses

The world we live in is no different. Between us and the Iron Age lies the Age of Clockworks and the Information Age, both of which infect our thinking about humans and their proper relationships to each other, to our gods, to our state, and to the universe as a whole.

From the Age of Clockworks we get the idea that the universe is supremely orderly, and completely understandable. The planets whirled through the aether like gears on a spoke attached to a central wheel on a cosmic clock. The whole clock, in turn, was tuned up, wound up, and set in motion by a great Watchmaker in the sky. Empires were interlocking systems of clockworks, with citizens, slaves, colonies, and economies all functioning in service to the operation of the great mechanism of the State, and the states themselves interacting together to move the world (for what are gears but circles of levers pushing always upon one another, transferring force down through a system?).

If the universe is a machine, then societies can (and should) be planned. People are cogs in the machinery of civilization, each playing a vital but highly constrained role, and woe betide he who stepped out of line. It is here that we get the final piece of totalitarian logic, and it is with us still today:

If the machine does not serve the interests of man, then man must be made to serve the interests of the machine—an intuition that almost perfectly inverts everything about how you might assume, a priori, that a world made by humans should work.

And it’s also an inversion that most of us indulge in every day when we say “my thumbs are too big for my phone.”

Of course, after Darwin and Einstein had their run through the watch factory, the clocks all broke. The world became a relativistic living system. Rigid moral codes (that varied for each class of society) gave way to an ever-growing bohemian sensibility. Economies shifted (uncertainly) from mercantile to open(ish) and from superintended machines to competition-driven ecologies where only the strong survived, then back to “managed.”3 Quantum uncertainty showed how everything in the universe effects everything else in an unpredictable manner, so every person became equally valuable—and equally disposable.

When the information age arrived, learning became an algorithm, the brain became a computer, and knowledge became a web whose structure looked suspiciously like the Internet, and network science became the explanation for all things, while Moore’s Law was the fount of all prophecy.

Live and Die by the Metaphor

Our culture is the conglomeration of some features of all these metaphorical views. When you are presented with a moral or political problem, you approach it first through the lens of the metaphors you use to think unless you have trained yourself not to—this is very difficult to do, and only works sometimes.

Many rationalists fancy themselves as approaching problems as if from a blank slate, but often they are instead operating through a metaphorical framework they don’t realize they’re using—and, most of the time, this metaphorical framework is based on the latest-and-greatest technological craze, because rationalists are always intellectuals, and intellectuals are always among the most well-fed members of their civilization.

This is not to denigrate the outsider’s view (I am one of the outsiders I would be denigrating!). The exercise of looking at a moral or practical problem through an alien framework is one of the most useful thinking tools we have, and it works because, just as each metaphorical framework has its advantages, it also has its blind spots. Culture is (apologies to Thomas Sowell) trade-offs all the way down.

Culture is, after all, the collective set of rules, norms, stories, and metaphors that shape the behavior and identity and solidarity of the people within that culture—but the shaping is not unidirectional. The people within that culture create the culture anew every generation, and the better fit those innovations are for the changing external constraints upon that culture, the more likely that culture is to adapt to and survive those changes...

...so long as those constraints are ones that human nature can abide.

The Bronze and Iron Age frameworks worked well for over a thousand years each, because these natural materials offer many points of commonality with human beings (who are also natural creatures). The Age of Clockworks did not last nearly as long, but it produced tremendous wonders and terrors precisely because its way of thinking was as well-suited to the design of complicated tools as it was ill-suited to the messy, complex reality of human nature.

Each of these metaphors gave the people who lived with them an understanding of the structure of the world that seemed to them as natural as breathing. They opened obvious avenues of inquiry and development, and they closed off others—sometimes so effectively that some advances (like the steam-powered railroad) which would have seemed obvious to people with a different metaphorical structure were overlooked for a thousand years or more.

In your study of history, learning to recognize the metaphors implicit in the worldviews of the past and the present takes you behind-the-curtain (a metaphor) so you can see the machinery (a metaphor) by which humanity operates. The more of these metaphors you learn, the more the weird writings and actions of the people in the past will make sense to you—and the less permanent our own way of looking at things will reveal itself to be.

Next time, we’ll examine race, sex, and sexuality, and whether (and how) these things are at all relevant to understanding the great figures of history.

This post is composed largely an excerpt of my forthcoming book Reclaiming Your Mind: An Autodidact’s Bible, which is launching on Kickstarter this July.

Contrary to popular perception, it is anathema, not abomination that constitutes the serious, unforgivable sin. Thus, Abomination (original definition): A cause of pollution or wickedness.

Anathema (original definitions): 1.A curse or malediction 2.Any person or thing anathematized, or cursed by ecclesiastical authority.

This metaphor also existed in some bronze-age empires, as in Egypt because of their dependence upon desert irrigation, but it did not become universal until the iron-age maritime empires.

A middle ground where competition persisted, but the governing authorities favored the larger firms. In other words, the economy is being thought of like a public park.

I thoroughly enjoyed your ‘Unfolding History’ series.

I mean I REALLY identified and appreciated the perspectives you put forth … and I read a lot and am hyper critical of most.

That said I was super fired up to stumble across public access to this ‘Reconnecting with History’ series this morning and have been devouring it in delight all afternoon.

Perhaps the commonalities we share in my imagination (Gen X, Bay Area, Burner, Educated, Annoyed) provide a loose framework allowing me to tap in effortlessly and pick up what you’re putting down with appreciation for the tone, metaphors, prose, and philosophy.

All the above being said, what the fuck kind of world do we live in where the factor for my paying you a couple of bucks for work of tremendous value is determined by my desire to let you know that I hope someday soon you’ll forge a pathway to connect your SIDEKiCK to a 4g LTE /5g wireless network, because I know you’ll share that alchemical experience with the rest of us hoping to bridge the gap and make technology great again.

I'm going to learn so much with this subscription, and that makes me happy. One question. I thought Genesis and Hammurabi were written about 700 years before Iliad and Odyssey? I'm not saying I know this, but I thought it.