The Rules Are an Illusion

The Secret Genius of the Midwit Meme

An Elephant in a World of Fake Rules

I’ve been thinking of Dumbo.

For those of you who were deprived of this essential childhood tale, let me bring you up to speed:

Dumbo is a circus elephant who is rejected by the other elephants for his freakishly large ears. The ringmaster, not willing to let an expensive animal go to waste, separates him from his mother (who violently defends his honor), makes him a clown, and relegates him to a life of profitable humiliation.

One night, after getting unintentionally drunk with a rodent friend, Dumbo awakens to find himself in the top of an elm tree. His buddy (the mouse) quickly deduces that Dumbo must have flown up into the tree using his enormous ears as wings, but he can’t convince Dumbo of this obvious fact. In desperation, he plucks a feather from a nearby bird and tells Dumbo that the feather is magic—as long as Dumbo holds the feather in his trunk, he can fly like a bird.

And he can. Dutifully clutching the feather, Dumbo soars happily through the skies, enjoying his newfound freedom…

…until the feather slips loose from his grip. His mouse friend, in desperation (as they plummet towards certain death) explains the lie and begs Dumbo to fly.

And, because this was a Disney film, Dumbo finds it within himself to fly, saving his own life and rocketing towards a future where he lives happily ever after.

Dumbo only ever tried to fly (sober) because a fake rule (“the magic feather makes you fly”) gave him the confidence to try.

Of Beginners and Experts

Don’t drive with your knees. Keep both hands on the wheel.

Show, don’t tell. Use realistic dialogue. Don’t use cliches.

Don’t drink. Don’t swear. Don’t lie. Obey the law.

The rules are everything: once you learn the rules, you’ve learned at thing. And people who are good at that thing have internalized the rules.

That’s the way we teach things.

But that’s not the way that things really work, is it?

Consider one of the notorious magic feathers of my own profession: “Show, don’t tell.”

It’s in all the advice books for new writers. It’s what we advanced authors tell beginning writers. And it’s great advice, except for one tiny problem:

It’s not true.

And no, I don’t mean it’s a “rule of thumb” that’s “usually correct” so it makes for good entry-level advice.

I mean that it’s pure, unadulterated horseshit. Just like Dumbo’s magic feather.

But we keep doing it, because we know something about writing that new writers don’t know, and wouldn’t believe—but that all writers will discover on their own if they hang in the game long enough and actually work at their craft.

And, worse still, it’s not just writing that works this way.

Almost everything, it seems, works this way.

The Truth is in the Telling

To continue with “show, don’t tell,” if I were forced to come up with a single bit of writing advice that is more ridiculous, I’d be hard pressed. (“Don’t use adverbs” is a good contender.)1

No, scratch “ridiculous.”

Try “destructive,” instead.

Why destructive?

Consider this description:

“Conan’s blood flushed hot in his veins. He cast about the throne room for an object upon which to wreak his vengeance. He seized upon a small bowl, carved of faceted jade and encrusted with gold—a holy artifact of his people. He lifted it above his head and threw it at the rough wall, where it exploded, a thousand green splinters tinkling onto the floor’s hard cobbles. How would he reclaim his honor?”

Paints a vivid picture, doesn’t it? Ornate, vivid, intensely visual?

Now, consider this:

“Rage seized him. With an almighty howl, Conan hurled the Cup of Scythia at the far wall. The priceless artifact shattered into nothingness. He was undone.”

The first version is a “show” passage. The second is a “tell” passage…and the second is clearly superior. It’s the kind of thing you’d expect to read from a writer who has his craft pretty well surrounded, who knows how to direct your attention, and why to direct your attention.

And it shouldn’t be surprising, because the purpose of narrative is to convey meaning, not to describe environments.

So why do we more advanced writers tell beginning writers to show-instead-of-tell?

Well, because we want to winnow out the competition, obviously.

Because almost every beginning writer has the opposite problem:

They use generic details. There’s “a bowl,” Conan is “angry.” If they describe the room at all, it’ll be a “large stone room.” They know kinda what they’re aiming for, but they don’t understand how to control the mind of their audience well enough that the audience will see, smell, hear, and feel what the writer intends.

That’s assuming they use any details at all. They may forget to describe anything with sufficient vividness for the audience to feel a sense of dramatic purpose. Everything is a white room, or a black stage, populated with blank slates.

So we tutors—the ones who have a few dozen books under our belts—lie. We tell new writers “These are the rules” because new writers want rules in order to feel like they know what they’re doing. We justify this kind of (often very lucrative) mendacity by reminding ourselves that most wannabe writers will suck so hard that they’ll quit, and most of those that stick with it will eventually figure out that the rules are fake.

This rule, and analogous ones in other fields, are a type of lie known as a “pedagogical lie.” It is a deliberate deception that is intended—by virtue of its falsity—to guide the object of the lie towards the truth (assuming they are sufficiently motivated).

In writing, the rules for beginners are all pedagogical lies. They are magic feathers. They provide imaginary structure to give newbies enough confidence to stretch out their wings.

They also serve to guide newbies away from activities that are perilous if attempted too soon.

And writing is far from the only field where these pedagogical lies abound.

The Lies We Tell Our Children (and Ourselves)

Consider music. Any kid that learned an instrument learned a few important rules:

You must play the notes as written.

A competent musician must play the notes on the beat, and on pitch.

Obvious, right?

It is…until you hear a master vocalist, or guitarist, take everything about a song they know backwards and forwards and make the tune their bitch.

Take, for example, this rendition of the childhood classic “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”

Notice how, in this rendition, the notes to the song are almost never played. The beat is held steady by the percussion section, but the two soloists slide all around on top of it—they play between the beats, around the beats, just above and just behind the beats, but almost never on the beat.

And yet, somehow, the tune’s flavor emerges anyway. By breaking all the rules, something pedestrian and cliche’d turns into something astonishing and memorable.

Watch any master craftsman at work, no matter their craft, and you’ll see the same thing. They have come to understand their discipline well enough that they see through the rule to its true nature, and they interact with it on that level. They work in accordance with its nature rather than the rules they were taught.

When a beginner tries to do this, the results always land somewhere on the spectrum between “boring,” “horrific,” and “ridiculous.” You can see it in an earlier scene of the same episode of Young Indiana Jones. I’ve been unable to find a pre-excerpted clip, so here’s the whole thing. Check out time index 23:00-23:30:

The trivial way to explain this is that “Our hero is trying to run before he can walk,” and that’s true enough. The entire production is a fantastic showcase of how one learns to run in any creative field, but there’s something deeper going on here, too.

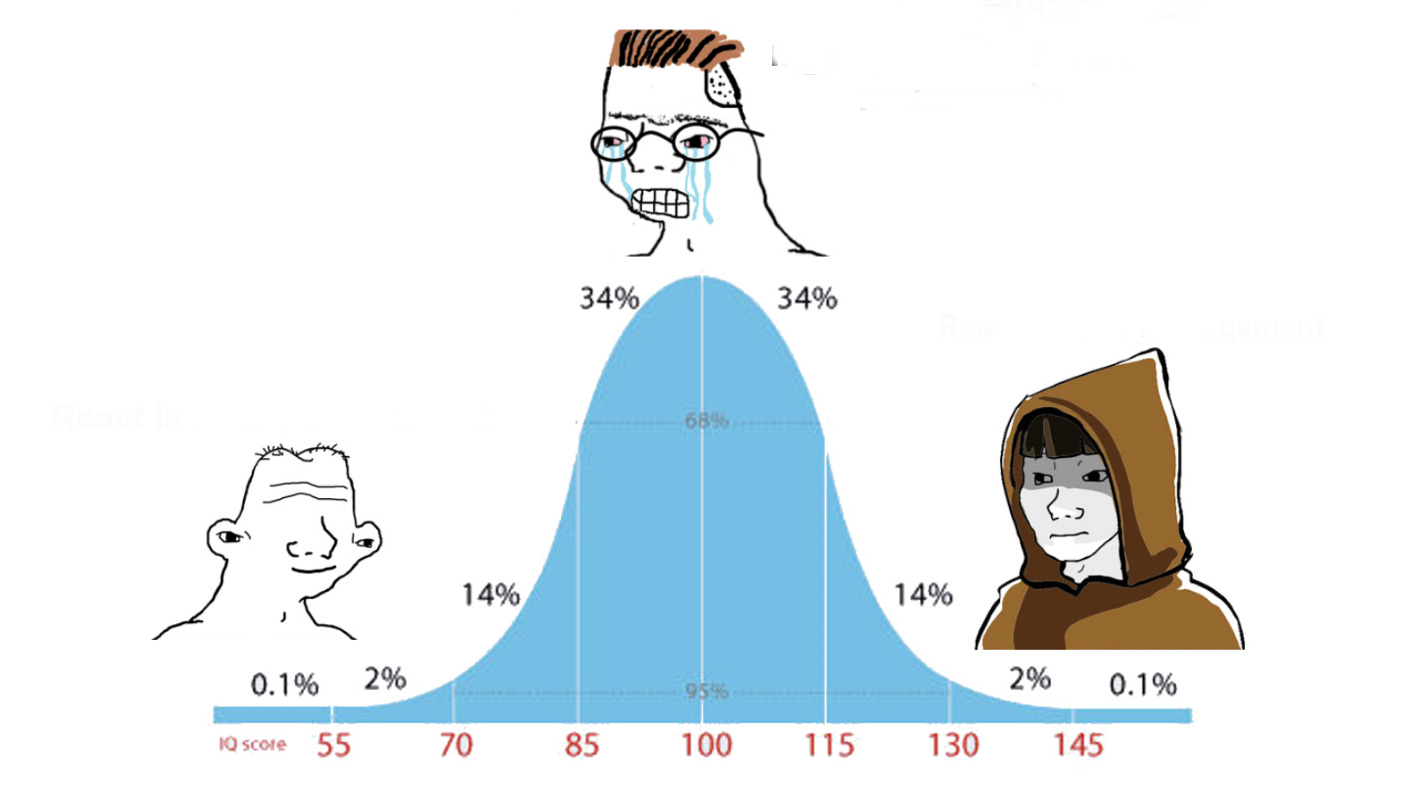

I assume everyone on the Internet has, by now, seen some version of The Midwit Distribution:

The basic idea is that the things that are obvious to the idiot also coincide with the wisdom of the genius, while those stuck in between have a differing, very sophisticated opinion that is (by implication) somehow untrue.

It doesn’t matter what part of reality you’re looking at, this tendency holds true surprisingly often…but it’s not because the people in the middle are stupid, and it’s not because the idiots are God’s beloved fools who can magically intuit everything.

It is, instead, because those who are masters understand when the basic intuitions are true, and why they are true, and how to use that knowledge to manipulate reality. Those trapped in the middle, on the other hand, were once idiots who saw how completely the idiots generally fuck things up, and they found within the rules a sort of salvation that allowed them to avoid those fuck-up states and make sense of the world.

But, in so doing, they invariably mistook pedagogical lies for eternal truths, and tied their personal value to them.

An idiot, for example, would look at a corrupt government and say “you can just do things.” A political master would, as well. And their actions might look identical from the point of view of someone who understands that the rules hedge against certain failure modes.

But history is never made by the rule-followers; it is always made by those who operate outside the rules (either because they’re too dumb to know the rules are there, or because they’re sophisticated enough to hold the rules in contempt, and break them with purpose).

In science and engineering, the name for this permissionless activity is called “innovation.” Upwards of 99% of innovators fail to achieve anything of note within their lifetime—sometimes, a small additional percentage will change the world posthumously.

In the arts, permissionless actors are called “pioneers” when they succeed, and “poseurs” or “pretenders” when they don’t.

In the social sphere, those who fail are called “psychopaths,” “evil,” “immoral,” and “degenerate,” while those who succeed are called “saints,” “visionaries,” “great men/women,” and “giants.”

Now, let’s get a bit controversial and look at some of the pedagogical lies we’ve all been brought up on.

“Nobody should take drugs (except when a doctor tells you to)” is a pedagogical lie. It’s one that we tell children because to successfully use psychotropic drugs without having them become your master requires both an extraordinary level of self-possession and self-awareness. But those who do have this level of consciousness are able to exploit their neurochemistry to create great artworks, generate scientific advance seemingly out of thin air, conquer continents, and found religions that endure for generations (if not millenia).

“A good person does not have more than one sexual partner at a time (or in a lifetime)” is a pedagogical lie. Most civilizations, most of the time, are mostly monogamous because human pair-bonding pushes us in that direction. But those of an unusual bent have, from time to time, made the maintenance of plural marriages and other unconventional relationship styles work well over the course of a lifetime.2

“Never play with fire” is a pedagogical lie. Someone who hasn’t yet mastered fire must take great care not to burn down his house, his forest, or his town. But someone who has mastered fire can terraform an entire continent, or shoot rockets to the moon.

In every single field, the midwit distribution meme applies, because those who seek to avoid failure find a reliable path to a good-enough life in following the pedagogical rules as if they were statements of truth. Sure, they confuse the map with the territory, but where the map is good enough, why bother with the uncertainty introduced by dealing directly with the territory?

And while the denizens of the dependable middle follow their map, those who are seeking to destroy themselves and those seeking to master themselves invariably wind up treading similar paths—paths where risk is high and poor judgment creates disaster. For those on the dangerous path, this isn’t a problem—those seeking to destroy themselves will do so, while those seeking mastery will either find it or die trying to do something they dearly value.

But, win or lose, those on the risky path will always wind up rocking the boat, disrupting the world for the comfortable middle…

…which is why, in any sufficiently mature field, culture, economy, or social system, those willing to assume such risks are loathed, castigated, defamed, censured, ostracized, and, in extremis, expropriated and murdered.

“Throughout history, poverty is the normal condition of man. Advances which permit this norm to be exceeded — here and there, now and then — are the work of an extremely small minority, frequently despised, often condemned, and almost always opposed by all right-thinking people. Whenever this tiny minority is kept from creating, or (as sometimes happens) is driven out of a society, the people then slip back into abject poverty.

This is known as ‘bad luck.’”

—Robert A. Heinlein

Risk Is Our Business

If you’re still reading this, you’re a member of a very small club in human history:

You’re someone who’s willing to seek out and endure uncomfortable experiences.

That means that you are at least flirting with a risky path.

Whichever path that may be, as you tread it you’re going to encounter pedagogical lies. They’re there for a reason:

They’re there to protect you from doing something stupid before you’re advanced enough to pull it off.

But, if you seek mastery in whatever art, career, or life-path you’ve chosen, you will eventually have to start putting away the lies like the training wheels they are.

Do not ignore the value and structure they bring, but notice also their shortcomings.

Pay attention to when they do not serve you.

Pay attention to when they blind you.

Keep one eye on the map, but prefer, wherever possible, the territory it represents.

And, unless you prefer comfort to mastery, don’t get stuck in the middle.

If you found this essay helpful or interesting, you may enjoy the Reconnecting with History installment on Understanding Before Thinking, and this essay on learning to think through language and story: Are You Fluent in English?

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. You can find everything currently in print here, and if you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

If you’ve been poisoned by this advice due to reading the dogmas of a certain very successful horror writer, you need look no farther than that writer’s own prose to see what a stupid piece of advice this is. In the quest to avoid adverbs, Stephen King’s writing winds up drowning in adjectives to the point of torturing the English language nearly beyond recognition.

I have documented a number of these characters in Unleashing Mystery and Madness and discussed the macro-context of pair-bonding and its odd exceptions and wrinkles in The Progressive Myth of Monogamy.

Way back when, I studied physics education. The beginner needs to be told what equations to use. The competent middleman knows how to find the equations that matter. But the expert... knows the physical principles and invents the equations to describe them.

They're beyond the math because they understand how the physics really works.

This has showed up when I, a retired rocket scientist, have tried to help my son with his high school physics homework. I can tell him how the system will behave and then we spend the rest of our time trying to identify the equations from his cheat sheet that will get that result.

So the curve from beginner to expert--pretty common. You have to use the rules until you reach the point where you understand enough to discard the rules.

Here's a dumb one we tell kids...bullies just need someone to be nice to them and they'll change.