This post is long with many images. Your email client may choke on it. If it does, read the original at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com

Darkness Upon the Deep

If you were to look at a map—any map, from any time—with new eyes unconditioned by your experience, you might notice that people tend to cluster in cities, and those cities—with some exceptions—tend to be situated only in certain kinds of places.

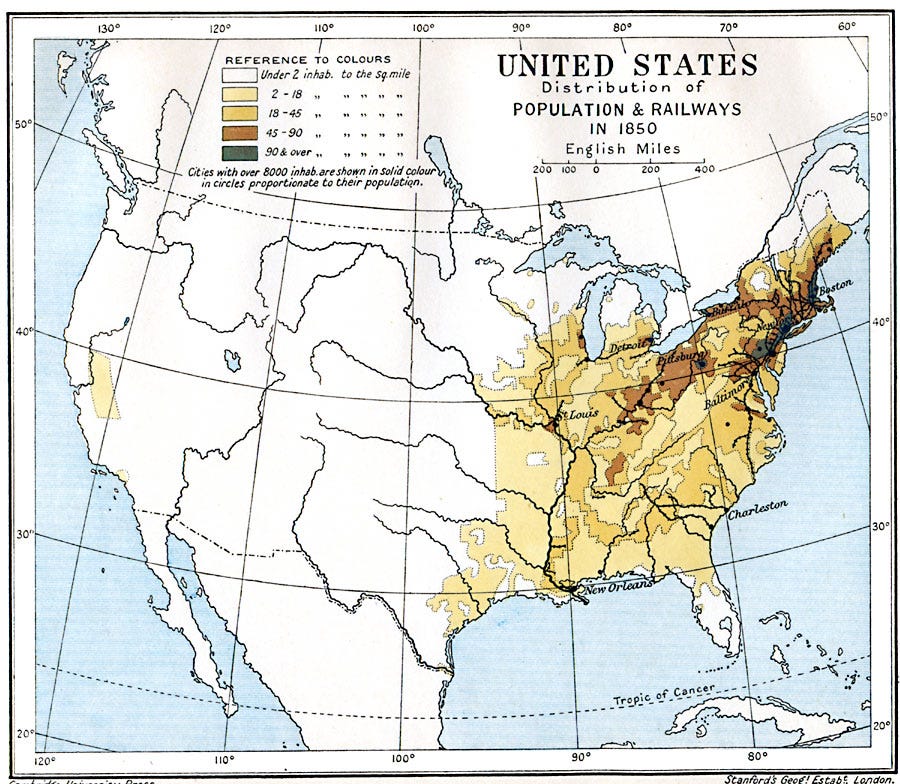

Take, for example, this map of the United States from 1850.

Or this map of China (this one’s from 2010, but China’s population distribution hasn’t changed all that much since 1850, even though its population has grown prodigiously in the interim):

Or this map of ancient Egypt:

Can you see it?

Every big population center is either on a sea coast, or in a river valley.

Kinda makes sense when you think about it. Sure, small bands of humans who know the secrets of their environment can survive in strikingly arid conditions—such as in the Kalahari, or the Arabian Peninsula, or the Gobi desert—but most people aren’t San, or Bedouin, or Mongolian.

Humans are a thirsty species. We need water to live, much more than food. In a pinch, we could live on grass and starve to death over the course of several weeks (or longer) as our digestive systems try nobly to extract some meager nutrition from cellulose. Without water, though, we’re rotting husks of beef jerky (okay, long-pig jerky) in less than a week.1

And that’s just what we need to drink. Our livestock, our crops, mining, pre-industrial power for doing useful work, chemical processes, metallurgy, machining, machines, server farms, and just about everything else we do or build depends on an ample supply of water. Hell, even the world’s cheapest form of travel (as measured in cost-per-ton-per-mile) requires water to float on. We don’t just have thirsty bodies, we have a thirsty existence.

The type of water matters. Potable water is for drinking, everything else waters plants and runs industry and floats ships.

And how the water shows up in your civilization also matters much more than you might think. Historically, those civilizations that are built around seamanship and the trade it brings are the freest, spontaneously re-discovering workable democratic forms of government and social management—Venice was an independent Republic for over a thousand years, the Vikings and Germanic tribes governed their affairs in a participatory fashion,2 the Greeks and Romans and Carthaginians all oscillated in and out of varying forms of participatory government, the Dutch were famously the freest people in Europe for centuries, and the pirates that sailed the Spanish Main during the Golden Age of Piracy all enjoyed a slice of the franchise, a slice of the pie, and the right to unseat tyrannical rulers.3

Agricultural riverine civilizations, especially those that practiced complex irrigation, often followed a different political course. Egypt, China, Babylon, Persia, Sumer, and the Indus River civilization were all regimented, harshly ordered, sharply stratified, and highly bureaucratized.4 In all cases, the impetus for the development of such byzantine governance was driven by the same factor.5

Consider:

You’re a subsistence farmer in a fertile river valley. You can easily grow all the grain you need to keep your clan alive, and you can pluck fish from the river. It works quite well, and the abundant food means your clan grows to staggering proportions.

But then, what with the fertile land and abundant water, some yahoo moves in upriver and starts pulling out fish, diverting water to irrigate his land, and dumping his sewage into the river. And he’s not the only one. The valley attracts more farmers, and someone builds a mill to grind the grain. Weavers pull the fiber from the cannabis and the wheat-grasses and the flax and make cloth. Dyers set up shop on the shore and use the water in their chemical processes, infusing beautiful colors into that locally-produced fabric.

As this happens, the river’s water turns brown with the cumulative waste. The fish begin to change or die off. Before long, your clan’s secure living situation is looking decidedly insecure. You gotta do something.

You might try to negotiate with those bastards upriver who are polluting your water supply...or you can go to war with them and wipe them out, taking their industrial works and lands for yourself to dole out to those in your clan.

But even if you do that, it will only be a few generations before family ties are loose enough once again that they won’t be adequate to enforce the agreements that keep your river valley from erupting into violence over the use of the water. Eventually you’re gonna need someone whose job it is to enforce those agreements. This is how God-Kings are born.

Those God-Kings, in turn, need mandarins to demarcate, plan, coordinate, and administer the water rights that those agreements are meant to guarantee—and those mandarins need a professional army to enforce the will of the mandarins.

Mandarin, noun.

Definition: A powerful government official or bureaucrat, especially one who is pedantic and has a strong sense of his own importance and privilege

Since the mandarins are nerds who do an unpopular job that is nonetheless necessary, they are in an ideal position to enrich themselves at the expense of their subjects without much fear of reprisal—and if they can grow their power, all the better, since they can use that power to further gut their subjects of power to rebel, revolt, or defect.…well, you know how it goes.

But water didn’t just shape ancient civilizations, or the heritage of countries like China; it swirls beneath the foundation stones of the two most powerful empires in the history of the world:

Britain, and the United States.

With the election and the holidays approaching, it’s a tough season to be self-employed. My partner-in-crime and I are both currently seeking gigs for editorial, layout/design, voice over, audiobook narration, and strategic consulting work.

I personally am also available as a tutor for anyone struggling with history, English, creative writing, or psychology.

Or you can help keep me writing and building interesting things by joining me here as a paid subscriber.

The British island maintained a fairly anarchic, localistic, participatory political system (even during the reigns of her worst tyrants), and that shaped its attitudes as it suddenly exploded onto the global scene during the Age of Discovery. It retained its ancient northern-European tribal norms far longer than the rest of Europe…because of water.

Not the English Channel—plenty of islands were conquered, subdued, and centralized long before Great Britain united and centralized—but because of the water on the island.

Britain is a damp place with loads of rain, more than its share of marshes, moors, mires, and bogs, where roads are difficult to maintain and pre-industrial travel is (or, rather, was) a bitch. No potentate in his right mind would waste his valuable time trying to micromanage a land like that, and so the Kings of England generally didn’t.

But eventually, as swamps were drained for farming and the agricultural surplus began to mount, the crown commissioned a series of canal-building projects to help get goods to market. As the canal network spread, the little island with four living languages (at least) integrated.

The integrated water transportation network meant that the industrial revolution, when it came, hit hard and fast, finding a nation without much in the way of a mandarin class, because the abundance of water meant that the waters of Britain never had to be centrally managed. The result was the freest economy of scale in the industrial world (freer even than that of the United States in some respects). It wasn’t until the Post-War era that managerial mandarins finally mutilated the British motherland and turned it into a deformed and dysfunctional shadow of its former self.

In the western United States, on the other hand, the rarity of water led to innumerable scuffles between farmers and ranchers, townsfolk and industrialists, urbanists and homesteaders as they fought (often violently) over who had the rights to what surface water. And since a single tickling stream in the western North American watershed can run for thousands of miles, water has continued to be the (or at least “an”) underlying driver of economic, ecologic, pyronomic, industrial, and agricultural affairs west of the Rockies to this day. Whoever controls the water controls everything it touches, and the struggle for water in the West has animated its history and art, including the Roman Polanski masterpiece Chinatown, which fictionalizes and memorializes one of the great water corruption scandals in American history.

When the Water Flows

As cocktail party conversations go, “water rights” is right up there with “Aunt Mabel’s plantar’s wart surgery” in its level of excitement and appeal. After all, we live on a water world, and our ancestors had the good sense to invent things like plumbing, reservoirs, wells, water treatment, and rotary pumps.

Go to your kitchen, turn on your tap, you’ve got potable water. Yeah, it might be more or less drinkable depending on where you live and how good your local utility is at maintaining its infrastructure, but if you live anywhere in a developed country, you’re unlikely to spend much time more than a couple minutes’ walk from a fresh water source.

Now consider:

For most of the United States, this state of affairs is less than a hundred years old.

Before that, your family would’ve had a well from which you drew water, either by hand or with a screw-driven pump (which, if it wasn’t an artesian well,6 may have been powered either by hand or by a water wheel). Sewage would have been processed on site (as it still is in much of the country, even in some major urban zones)7 through either composting or with a miniature on-site sewage treatment plant called a “septic system…” assuming it wasn’t just dumped into a cesspit (the least hygienic and pleasant of the bunch).

But, excepting those living out in the boonies, we don’t really think about things like “water” anymore, and we’re not alone. The mandarin class in our civilization rarely even notices the issue. Since the 1960s, it’s become much more fashionable to prevent the development of water infrastructure than to facilitate it. The idea of water rights playing an existential role the relationship between neighboring countries on this continent (or even in Europe) has almost faded from living memory.

Our mandarin class now concerns itself with the levers of power in the modern world:

Finance, war, and energy.

And our consent isn’t sought on even these topics so much as it is on topics like pornography, abortion, and the personalities of our elected leaders and their followers.

Both we plebs and the ruling class have long enjoyed the luxury of being insulated from reality, especially from this most basic kind of political reality.

We become so accustomed to water wealth that our ruling class struggles to comprehend that something can actually go wrong with it. Municipal utility boards are riven with scandals such as has been unfolding in Southern California, and plagued by infrastructure problems and poor judgment they barely command notice even when they become a national scandal (as happened in Flint, Michigan).

The water wealth has made such bodies fertile ground for demonstrating the Iron Law of Bureaucracy:

First, there will be those who are devoted to the goals of the organization. Examples are dedicated classroom teachers in an educational bureaucracy, many of the engineers and launch technicians and scientists at NASA, even some agricultural scientists and advisors in the former Soviet Union collective farming administration.

Secondly, there will be those dedicated to the organization itself. Examples are many of the administrators in the education system, many professors of education, many teachers union officials, much of the NASA headquarters staff, etc.

—Jerry Pournelle, The Iron Law of Bureaucracy

Those kinds of shenanigans are one thing when the water flows, but what happens when the water stops?

When the Water Stops

The central valley of California is a vast, ultra-fertile farmland at the foot of a mountain range that harvests the brunt of moisture coming off the Pacific. Despite this, for much of my life (the bulk of which was spent in California) the state has been plagued by water shortages even when not in a drought (as measured by rainfall and snow pack). Why has this happened?

In the case of California, once-expansive reservoir and aqueduct construction projects were put on ice as a result of environmentalist pressure, which began ramping up in the late 1960s. Even in drought years, the northern part of the state generally gets more water than it can use, but its abandonment of development means that, despite this natural water wealth, farmers have been forced to drain lakes and draw-down aquifers to the point where some agriculture in the region (the most naturally fertile land on the continent) is becoming untenable—all while millions of cubic acres of water wash out to sea through the Sacramento river delta.

As far as the southern part of the state…the less said about that situation, the better.

Despite problems like this in California, and the looming threat of such problems in part of the midwest, water rights just aren’t something you hear much about. At best, you will occasionally get a sideways acknowledgement of the importance of water rights via a treaty negotiation that prioritizes other considerations than the reliability of the water supply (as happened in this year’s re-negotiation of the Colombia River watershed agreement between the US and Canada). At worst (or at normal), you don’t hear anything about it until the water stops working.

But the water is disappearing.

Surface water infrastructure development across the west has failed (deliberately, as a result of lobbying) to keep pace with the needs of the population, of industry, and of agriculture—all while the growth of population, the water-hungry industries, and the thirstiest forms of agriculture are being actively subsidized (as they have been for decades) by the policies and largess of the US Federal Government. From Colorado to the Dakotas to California, aquifers are running low and running out because the water we use is being pumped out of the ground instead of caught on the surface.

When the water eventually stops flowing out of the ground, the oil and gas wells will stop coming online in a ready fashion, the cities will ration and scramble, and hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland will be left to bake in the sun (which kills soil bacteria and denudes the land of fertility.8

These situations, like many others across the west, exist because our mandarin class no longer understands its job, or why its position exists in the first place. When the mandarins so lose track of their most basic function that they abandon the maintenance of the system they depend on, the system starts behaving in strange ways.

Water is life.

It is also the original basis for, and ultimate justification of, any administrative state.

When the Nile floods, a civilization begins.

When the river runs dry, the desert advances into what was once prairie, forest, meadow, and home.

You can have all the arguments you want about drugs, deficits, abortion, industrial emissions, vaccines, and internet traffic you want…

…as long as your government is water-tight.

If it’s not? The rest of that shit ain’t gonna mean much, in the long run.

If you’re looking for tales to transfix your imagination, you can find my novels, short stories, visions, and dreams (along with some how-to books and literary studies) by clicking here.

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. If you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

This column is a big part of how I make my living—bigger now due to recent exciting events which you can read about here. Because of this, I’m offering a 20% lifetime discount off the annual subscription rate. If you’re finding these articles valuable, I’d be honored to have you join the ranks of my supporters!

The exact timing varies depending on things like temperature, ambient humidity, and activity level.

The Pan-European Gallic (Celtic) civilization was also seafaring, at least in those locales where such was possible, but ancient information about their system(s) of government does not survive beyond the fact that they had local chieftains/monarchs, were organized hierarchically, and kept slaves (as related by Julius Caesar in The Gallic War and confirmed by archaeological digs). How exactly their civilization and governance functioned, what rights individuals had, etc. are a matter of controversy among historians, as is whether the Scottish clan governance models of the middle ages are a reliable guide to the ancient Celts.

See The Invisible Hook by Peter Leeson

In the case of the Indus Valley, this is an educated guess based on the remaining architecture and artifacts, as no written records survive.

See Irrigation Civilizations by Julian Haynes Steward

i.e. one that is under geologic pressure, so the water emerges in a fountain.

A friend of mine who lives in San Diego, in a 1980s subdivision, uses a septic system, as does every other house in his area.

You don’t really expect them to let it go back to pastureland for bison, do you?

recent floods in spain due to damn removal rather than 'climate change'.