This post is long with many images. Your email client may choke on it. If it does, read the original at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com

Aeneas was a Trojan warrior who, after the fall of Troy, struck out from the ruins of his civilization to find a new home. At the end of his travels, he founded the City of Rome, sowing the seed of an empire that eventually conquered and subjugated the Greek civilization that had razed his beloved Troy. His tale is told in Virgil’s Aeneid, a work of perfect subversive symmetry. This Roman poet took Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey, then turned it into a heroic tale undermining the Hellenic world and championing the Roman one.

Great civilizations depend on founding tales involving great heroes. If the actual heroes that did the job fall out of memory, or aren’t fit for the cultural role, better heroes get invented and stuck in their place. The point of such heroes isn’t to be historically accurate—when they are, it’s a happy accident—it’s to provide a rallying point and an identity touchstone for the civilization at whose root they allegedly stood.

Such a hero sets the tone for his civilization.

But even when they’re not purely mythic figures, heroes found civilizations. Not to get all “Joseph Campbell” on you, but that’s just the way it goes. Those heroes might be ones worthy of a story book, or they might be a set of scribes hiding deep in an underground city while wave after wave of siege-engines washes over them, madly cobbling together a legendarium that will allow their tribe to withstand the forces of cultural imperialism that they will be subject to once the sieges succeed.1

The men who wrote the Hebrew Bible (who I am describing) were heroes, but they weren’t the kinds of heroes you can rally a culture around. The figure of Moses on the other hand, who draws upon Sargon and Gilgamesh and Apollo (among others), is the kind of character who could serve as the foundation for a civilization so durable that it can survive just about anything, for thousands of years.2

But just because some of the greatest of such characters have been relegated to the domain of myth (either because they were mythical in the first place, or because everything but the myths about them have disappeared from the historical record) doesn’t mean such characters don’t exist in real life.

Caesar existed. We have the books he wrote. Galileo existed. So did Newton, and Goethe, and Hereclitus, and Democritus, and Washington, and Henry VIII, and Victoria, and Ismbard Kingdom Brunell, and Edison, and and and…well, I could go on all day.

I am generally an opponent of the Great Man Theory of history, because it ignores the actual events that motivate people. It is not often true that a great historical figure is motivated by lofty goals such as “securing the future of humanity” or “freeing the people” or the like. Most of the time, lofty goals are more personal, such as Isaac Newton’s desire to plumb the secrets of the universe so that he might know the mind of God (and possibly discover the Philosopher’s Stone, which would let him live forever).

Even more often, the goals of great historical figures are banal. Galileo and Edison were interested in a quick buck that could lead to even more quick buck. Da Vinci liked tinkering with things that would impress beautiful young men into his bed. Washngton et.al. wanted their government to treat them like the landed gentry they were, and to stop imposing taxes in absentia. Gutenberg wanted to pay off a bad debt he got into for stupid reasons.

But in most cases, the grandiosity or ordinariness of the motives don’t matter as much as the sort of person around whom the tide of history turns:

The genius.

The Genius Population

Let’s talk IQ. In certain circles, “genius” has a particular IQ level associated with it. Psychologists generally consider an IQ of 125 or above “genius or near-genius” level. Mensa famously requires a documented IQ of around 130 (depending on the test) for its members, which equates to roughly the 98th percentile.

Think about that for a moment.

~130 IQ, well into the psychological “genius” range, is a level at which you’re smarter (in the way that IQ measures smarts) than 98% of the rest of humanity. So let’s do a bit of math.

There are around 8 billion people in the world.

Two percent of those possess a genius-level IQ.

That means there should be 160 MILLION geniuses running around. We should be absolutely swimming in world-shakers.

Okay, sure, a lot of those people live in China and India where genius isn’t readily given the opportunity to flower, or in the third world where things like disease and nutrition limit the potential for IQ development, so let’s narrow our focus. If we were to limit our analysis to the United States, where the population is around 350 million, we should have around seven million geniuses knocking around.

In any normal universe, that many geniuses should make short work of the problems of good government, good management, innovation, and everything we need to get our civilization rolling into the kind of futures we read about in science fiction (or, at least, the hopeful subspecies of that genre).

This raises the natural question:

Where the hell are they?

The Subspecies of Humanity

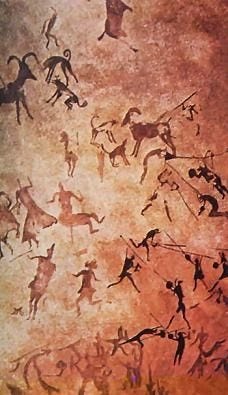

Actually, let’s put that question on hold for a moment and look at another side of the human equation. We are not, after all, individual islands. We all enter the world as the result of the actions of others, we are nurtured from the bodies of others, we develop as individuals in the context of relationships both fair and fowl. We are a social species, and we are a predatory species, and our depredation is social in nature (i.e. we are most successful as predators when we use our sociality as a weapon against our prey—such as is done with the exhaustion hunting method practiced by the San Bushmen).3

When hunting, or engaging in warfare, the team social dynamic rules the day. Hunting parties don’t just have shooters (whether wielding spears, bludgeons, bows, or guns), they also have one or more of the following: trackers, spotters, flushers, drivers, scouts, and sometimes cooks, who all work together to secure the kill. By playing these different roles, human hunters function like a pack of wolves or lions or hyenas, pushing prey into a good kill position, and bringing home the bacon (or venison, or whatever).

All human sociality is organized this way. We divide labor amongst ourselves according to our talents. It works at every level from the division of labor between the sexes (due to reproduction, strength, and native social style) to the division of labor between leaders and followers, craftsmen and herdsmen, farmers and office workers. Even within families, we specialize and trade.

If we were to characterize this kind of division of labor broadly, we might call it “economics.” It’s not exactly concerned with money, but it is utterly concerned with the stuff of survival from day to day, and generation to generation.

That’s great for a civilization (of any scale) that exists in a stable environment, but what happens when the environment changes? Ice ages, the rise of rival nations (or tribes, or whatever), the extinction of favored prey species, famines, and social decay can all potentially cause the extinction of a people-group (and, if their luck is very poor, their entire culture and genetic line).

People-groups have succumbed to these kinds of pressures throughout history.

But we are here, at the peak of human technological civilization. How the hell did we get here?

If we look at how humans behave in different situations, we find that the division of labor goes a lot deeper than just occupation, inclination, or reproduction. We have also a division of fundamental personality orientations that underlie everything else about how we think and behave.

If you were to visualize the social architecture of humanity as a landscape of possibilities,4 you could then visualize any concentration of human activity as a hill on that landscape. Every literary genre, art form, business, industry, religion, and nation-state is a hill.

Now imagine that there are also possible hills, where potential lies. When you have computer applications as a landscape, the early visible hills are things like accounting, census-taking, word processing, and games. As those hills are built higher, other neighboring hills become more visible.

Every hill is a realm of opportunity.

But between the hills lie valleys of desolation. These are places filled with danger, bereft of obvious opportunity, where only a fool would venture when he’s got a nice comfortable hill that he can build a life on.

The vast majority of humans are content to address the world they live in. We’re born into a culture, we go to school, we specialize, and we climb our way up the part of the status hierarchy we feel we have good access to. Let’s call these folks “Hill Climbers.”

But not everyone is cut from this cloth. Some people can’t knuckle under to the system unless their life depends on it, and sometimes not even then. In a tribal environment, these are the folks that wander off alone into the woods or across the vast plains to see what’s over the horizon. In our world, they’re the people who climb El Capitan or walk on the moon “because it’s there.” If they don’t, they might slip into a bottle or a syringe to cope with the banality of life. They’re restless souls with itchy feet. These are the “Valley Crossers,” humanity’s scout troops that boldly go where no one has gone before, and usually die trying.

And then there’s a third group, who have some overlap with each of the first two. These are the people who like being the masters of their own destiny, so they invent things. They build businesses, they organize revolutions, they design organizations, and birth technologies. These are the “Hill Builders.”

Societies continue because most of us are Hill Climbers. They grow to prosperity thanks to that minority who are Hill Builders. They survive calamities due to the evolutionary cannon fodder we’re calling Valley Crossers.

And, most importantly, the really great movements in history, the “Great Men” around who the course of civilization turns, are those inclined to cross valleys and build new hills in new parts of the landscape.

They are, each of them, an Aneas of their world.

Crazy though it sounds, this column is what keeps the lights on and the dogs fed. If you’re getting value from these posts, please consider joining up and supporting my endeavors.

A Wrinkle in Mind

During my time in Silicon Valley, I had the curious experience of being part of a startup that lived in a tech incubator. I was the dumb guy on the totem pole at a company that had an average founder IQ of well north of 180. After being referred to the incubator by some boffins at Stanford who spotted the lack of go-to-market business acumen on display among our inventors, the team wound up in an environment where we hoped we could get some solid business advice and perhaps secure a final partner to round out the team—a Jobs or Gates to go with our resident crew of inventors, strategists, and communicators.

Within a month of being at the incubator, though, I got a sinking feeling.

The companies that were launching well had a quality that we lacked, and that we were unlikely to get:

They were staffed by average geniuses.

When you study psychometrics and circulate among people who range from Very Smart to Holy-Shit-They-Make-Brains-That-Big? smart, you get to the point where you can peg someone’s IQ to within a standard deviation simply by listening to how they talk—not to their vocabulary, but to the way their thought is structured.

With every ascending standard deviation, the way that someone engages with the world shifts. To your average educated person, the difference between someone like Steven Pinker or Michio Kaku and someone like Jordan Hall or Nasim Taleb is almost imperceptible. To someone who walks in these kinds of circles (which I have always done, by accident of birth), these two sets of minds are not even in the same cognitive universe.

The Pinkers and Kakus of the world engage with reality mechanistically—they see cause and effect with unusual clarity, they can construct excellent arguments to support their pet theories, and they are pretty good at spotting errors of thought in other people who are much smarter than they are.

The Halls and Talebs of the world engage the world chaotically. In a formal setting, a sentence rarely exits their mouth that doesn’t take into account the complex interrelationships between apparently disparate parts of reality. When they look at the world, they do not see mechanisms, they see ecologies, and they actually understand the ecologies that they see.

The geniuses who launch successful businesses in established industries are usually in the Pinker-Kaku IQ range. They’re usually specialists who know their way around their corner of the universe and are keen to connect it to neighboring areas.

The geniuses who found new fields, on the other hand, are in the Hall-Taleb range (or higher). There are far fewer of them…and most of them aren’t interested in business except as a launching point for a life oriented towards other aims.

Those lower-tier big-brains have an advantage over the higher-tier ones, in the form of something that used to be called the “Common Touch.” They understand how smart normies (what online geeks derisively call “midwits”) think, and so they understand very well how to condescend5 to play on their intellectual level. It’s a useful skill.

It’s easy to simulate the world-engagement mode of someone a step or two down the IQ scale, but that simulation becomes harder the more someone’s cognitive capacity differs from your own.

And, crucially, it’s almost impossible to simulate the world-engagement mode of someone a step above you on the IQ scale. The reality they experience, moment-to-moment, is so fundamentally different from your own that the gap is all-but impossible to bridge. You can appreciate the fruits of their genius, but you can’t replicate them, or even simulate them enough to imitate them well.6

Take, for example, Jimi Hendrix. Any competent student of the guitar can stack effects pedals and imitate Jimmy’s basic sound, and any competent musician can memorize his performances and play them back well-enough (if this wasn’t possible, music students wouldn’t be able to perform pieces that had already been composed). But to create those performances, one has to see the sonic landscape and understand (intuitively) how the math of the fretboard affects the fuzzy chaotic realm of the human soul. This process isn’t puzzled out through problem solving, it’s simply done, as if by instinct.

Humans tend to play to their strengths rather than their weaknessess, and this tendency persists among those who are cognitively gifted. Specialization is the natural result of playing to one’s strengths. This means that the more rarefied someone’s IQ is, the more prone they are to getting caught in mental cul-de-sacs; not because they’re not smart enough to learn other things, but because the process of doing so requires experiencing the humiliation of being a beginner all over again.

At the tech incubator, the the most important players on my team were way up in Hall-Taleb territory (and beyond), and highly specialized, so every interaction with the folks who actually knew how to launch a successful business was fraught with perpetual, bi-directional failures of communication. It became clear very quickly that we were not going to get the traction we’d hoped for.

IQ, it seems, is not as general-purpose as it’s cracked up to be, which makes the genius population uniquely vulnerable to social selection pressures…and deprives the rest of us of the fruits of their genius.

Putting the Power Down

It takes more than genius-level IQ to make a tractable genius. It takes emotional qualities as well. Restlessness, ambition, and broad curiosity are important, as is a spectacular amount of disagreeability and a modicum of resentment.

In other words, something has to drive the gifted person out of his ghetto.

The life he lives must be uncomfortable enough to push him to pursue the difficult, the impossible, and the socially unacceptable. Otherwise, he could just get a job and climb the established ladder-rungs (which is what most genius-IQ types, in fact, do).

Do well in school (a breeze), get a good job in a promising industry (pretty easy if you do well in school and are moderately socially adept), do your job, play the political game, and you can secure yourself a tenured (or equivalent) position that sees to your financial security and your social esteem. For someone holding all the cognitive cards, even massive childhood trauma isn’t necessarily a permanent impediment to career success—which is a good thing, because the smarter someone is, the larger trauma load they’re generally carrying around.7

The Morality of Intelligence

How many times have you heard a parent express approval of their child—from infant to middle-age—in terms of their intelligence?

“You’re so smart!” from the lips of a parent is, in our culture, the semantic equivalent of “I love you.” Similarly, “You’re so stupid!” is the semantic equivalent of contempt.

A smart child, after all, is a validation of the parent’s being. She proves her parent’s genetics were good, that they raised her well. Especially if he or she conforms to the world well enough to be the family’s champion (and the child does not otherwise hate its parents), a smart kid will ensure the parents’ material comfort in old age, because that kid will be financially successful. She’ll carry on the family line, validate the family honor, and create opportunities for everyone.

So, we treat intelligence as a moral dimension.

But it isn’t.

Regardless of how genetically-determined intelligence is, the horrible truth is that you don’t have much more say in your own IQ than you do in your height. Both have genetic and developmental components (including early childhood nutrition) that are entirely out of your control, and both are more-or-less set by the time you hit the mid-point of puberty.8

This moral dimension fuels a general social bias against achievement and cognitive development. Someone who is noticeably smarter than their fellows occasions resentment in others, who are keenly aware of their own relative cognitive inferiority and thus fancy that the smarter person thinks too well of themselves. And, especially in childhood, smart kids are equally prone to retreating into their intellect as a way to cope with the social isolation they experience as a result of their brainpower, and thus often comfort themselves by cultivating a self-image of superiority-by-virtue-of-intelligence.

The dynamic is similar to what you see around wealth disparities or athletic disparities, but cognitive disparities hit people on a much more personal level. Being in the presence of someone markedly smarter than you can feel demeaning, while being in the presence of someone markedly stupider can feel isolating. Either way, both sides of the coin are prone to misery, and to coping with that misery through egoism and cruelty.

This dynamic of mutual resentment, however, isn’t quite enough to explain the dearth of genius on display in our world.

The Hill Climbers

Given the utility of having Very Smart People do Really Cool Things, it would seem to be in the interest of a healthy civilization to provide as many avenues as possible for the cognitively gifted to flourish. The rest of us would then be in a position to harvest the benefits from the worlds they open up.

Unfortunately, humans are not quite so rational. As you can see from the above, the social difficulties experienced by the cognitively gifted are fed by the fact that humans are disposed to prize status above all other things. Wealth, power, and officially-validated achievement (medals, awards, academic degrees, etc.) are proxies for status, and because of the social nature of most such achievements, that vast majority of humanity I’m calling the “Hill Climbers” spend most of their lives optimizing for status to the exclusion of all other things.

This leads to a pretty sharp churn in elite circles:

When a hill is first established, the only people qualified to climb it are those who actually have the chops to conquer it. Such people are highly agentic, highly disagreeable (they have to be in order to be willing to invest their live in proving out terrain that’s not yet been socially validated), willing to break the rules or make up new ones, and exceptionally driven.

But fast-forward a couple generations, and the existence of the hill (and the status associated with climbing it) attracts those who are interested in social climbing for the sake of social climbing. Where once you needed the audacity of a John Carmack to build a cool video game, now you only need to be able to code reasonably well and get a job working for a company that someone like Carmack built and then sold. Where early hill-climbers had to sleep on couches and live on instant ramen in order to secure their place in the social hierarchy, the late-comer can do well so long as he is adequately intelligent and has a reasonable facility with office politics. These qualities alone will land him a comfortable, respectable position.

Not long before his death, I had the privilege of interviewing John McCarthy, the inventor of Artificial Intelligence and pioneer of several foundational technologies in computer science. He lived in a comfortable home in Palo Alto, which he’d purchased back when the neighborhood around Stanford was a modest middle-class environment. He’d made a fortune in the meantime, but getting to the point where he could buy that house was a hell of a struggle for him. Meanwhile, during that same year I sat in McCarthy’s living room talking about the future of humanity, some friends of mine in their late 20s who worked database-monkey jobs at places like Intuit were refitting half-million-dollar fixer uppers and feeling no financial pain. It was a good era to hitch your wagon to the tech train.

A few years later, the market was so saturated that Very Smart People working at Facebook were struggling to make ends meet, despite living in relative luxury. And they hated people like Carmack and Zuckerberg because those people “got lucky.” They were “no better than me,” but they got to be on top of the world, so they deserved to die in a fire.

This is the fruit of a stable civilization, and it’s why civilizations fall. As a hill solidifies and becomes a valid status hierarchy, its tolerance for genuine merit collapses. The presence of genius in its midst gradually becomes intolerable, because it gives the lie to the comparatively modest achievements of succeeding generations. And, because humans are lazy, most would rather content themselves on material comforts leavened with resentment rather than take the risk of striking out across the valley to find a new hill that’s just being built.

After all, they might fail, and then where would they be?

Resentment thus builds across generations, and the geniuses that build their hills gradually get expelled on flimsy pretexts: They’re old, they’re smug, they’re out-of-touch with “current morality” (itself merely another sort of status game). They’re loose-cannons, out of control, a threat to stability. They need to be constrained with regulation, their behavior needs to be brought under control. Their power makes them, ipso facto, not-to-be-trusted. They must be done away with to “make room” for “new voices.”

The fact that they themselves were once the new voices, who made their own room in the world because they didn’t fit, doesn’t seem to occur to the late-comers.

But if the “old guard” doesn’t simply accept the new constraints, or acquiesce to exile into the outer-darkness, then something must be done about them.

The Outer Darkness

Some such figures, of course, do seem to accept exile. They build their hills and then move on to other things. Sometimes they build more hills. Just as often they retire to a quiet life because they don’t actually care too much about money or fame (and often come to resent at least the fame part of that equation).

One of the qualities involved in building a new hill or crossing a new valley is, after all, the ability to not give a fuck about the esteem of those who aren’t worthy of notice. I have sat in the living room of more than one retired rock star, startup founder, genius academic, filmmaker, or inventor who—at a fairly young age—re-focused their energies on far less public pursuits such as farming, having a family, studying esoteric corners of interesting religions, and attempting to quietly unravel the source code of the universe. These are pursuits that don’t require great gobs of capital or social esteem. These pursuits are start-ups of the soul. The provide meaning, rather than riches—a far better way to spend one’s life than forever fighting for position against those who, themselves, couldn’t manage to build hills themselves.

Greatness is never appreciated in youth, called pride in middle age, dismissed in old age, and reconsidered in death. Because we cannot tolerate greatness in our midst we do all we can to destroy it.

—Babylon 5

Second-Class Genius

It’s rarely the hoi polloi that affect this consignment to the outer darkness. Instead, it’s usually done by Very Smart People who are intelligent enough to recognize first-class genius in others. A tenured professor at an Ivy League school may be flush with esteem and opportunities, but put such a character in a room with a maverick genius who lived life on his own terms and—unless the professor is a person of exceptional character—he’s likely to feel very small indeed.

The academy is filled with these second-class geniuses—people of astonishing IQ and erudition who don’t have the other personal qualities required to actually shake up the world—and they are keenly aware of their own uselessness. Ever wondered why flashy idealistic systems (communism, environmentalism, critical theory, and other such highly sophisticated and politically potent intellectual game-spaces) are so popular and well-regarded among academics despite bearing very little connection to reality? It is precisely because they bear so little connection to reality. They’re a fine place for someone with great intelligence and mediocre grit to build up their own bulwark of superiority against those who actually make things happen in the world.

The crabs in a bucket climb over each other for the top spot. Any person—or way of doing things—that allows escape from the bucket implicitly calls into question the value of the bucket itself.

This is also why, post-retirement, you so frequently find the world’s great geniuses hanging out with the proles. The previously-mentioned Jordan Hall retired to a small town in Appalachia and attends a small church there. I know three former Facebook executives who did the same thing, and two engineers from the Apollo project who spent their later life hanging around biker bars and arguing about motorcycle customization with the Hell’s Angels.

On the other hand, you have figures who—either for reasons of personal hunger or external pressures—are unable to leave the game, so they continue to cross new valleys and build new hills until they die. This is the domain of the serial entrepreneur and the artist who dies with his boots on. This is where you find people like Johann Goethe, Thomas Edison, Elon Musk, Robert A. Heinlein, Ismbard Kingdom Brunel, George Soros, Bill Gates, Stanley Kubrick, Douglas Adams, Napoleon, and Leonardo Da Vinci.

The Nature of Genius

Whether mythical or historical, those great names I’ve mentioned are the embodiment of valley crossing and hill building, and some (like Napoleon) were also excellent hill climbers.

While these folks all undoubtedly possessed genius-level IQs, high IQ is a lesser factor among several. Most high IQ folks in today’s world are—like most other people—hill climbers. They code. They work at big companies. They do unremarkable jobs and their names are rarely remembered.

But genius—real, world-beating genius—requires creativity. It requires ambition. It requires courage. It requires restlessness or discontent.

And, most importantly, it requires the ability to ignore the scrabbling envy of the aspirant class, who would rather destroy greatness than admit to themselves their own mediocrity.

Most “geniuses” are idiots.

Because they would rather sit atop an ash-heap made of the skulls of their betters than strap into a rocket they didn’t build, and ride it to the stars.

“Throughout history, poverty is the normal condition of man. Advances which permit this norm to be exceeded — here and there, now and then — are the work of an extremely small minority, frequently despised, often condemned, and almost always opposed by all right-thinking people. Whenever this tiny minority is kept from creating, or (as sometimes happens) is driven out of a society, the people then slip back into abject poverty.

This is known as "bad luck.”

—Robert A. Heinlein, Time Enough for Love

If you’re looking for tales to transfix your imagination, you can find my novels, short stories, visions, and dreams (along with some how-to books and literary studies) by clicking here.

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. If you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

This column is a big part of how I make my living—bigger now due to recent exciting events which you can read about here. Because of this, I’m offering a 20% lifetime discount off the annual subscription rate. If you’re finding these articles valuable, I’d be honored to have you join the ranks of my supporters!

This is one of the newer theories of the authorship of the Torah and Tanakh, the collections of Hebrew and Jewish literature that Christians call the Old Testament. It may or may not eventually supersede the older theory that the text was compiled by scholars during the Babylonian Exile. The resulting paradigm, in either case, is the same.

Spoiler alert: It has indeed survived for thousands of years, so far.

This isn’t a political statement—collectivism, individualism, communalism, and other social arrangements and their attendant moral philosophies are all building upon the same basic human model, championing some qualities and suppressing others.

I am using this term in its archaic, positive sense rather than its more modern, derisive sense.

You can see how badly it fails in fiction featuring genius characters. Two examples that were relatively contemporaneous to one another are the protagonists of House, M.D. and Numb3rs. The former is a medical mystery drama, the latter a crime drama, both of which ran on network TV over the last couple decades. The writers of House either were (or had intimate familiarity with) genius-tier intellects with a good grasp of the mechanics of lateral thinking and complex problem solving. The writers of Numb3rs, on the other hand, were using a gimmick and a calculator.

Discussed with great incisiveness by Meghan Bell, here:

There is an exception here for the exceptionally traumatized. Pain is a kind of cognitive load, and someone who is in pain—emotional or physical—is always stupider than that same person when not in pain. In IQ terms, the difference can amount to several standard deviations in score. I have known a number of certifiable geniuses who didn’t actually discover their own cognitive potential until late in life, once they had begun to scramble out of the cognitive/emotional cesspit they’d been born into.

I have had the privilege of raising a hill builder and I'm having fun watching no matter whether failure or success is the outcome each time. One thing I didn't realize would be important that has turned out to be was ignoring social climbing or wealth competition. As in, just because you could hang out with X crowd doesn't mean you should or that you even want to. I wonder what makes some people impervious to those trappings. Laziness or just an aversion to fakery? One thing I'll say about genius level humans that seems to be a condition for a high iq is a bit of madness. Anxiety, depression, bipolar mania - these seem to be the price to pay.