The summer I turned sixteen, I worked grounds staff at a summer camp. I got the job through pure nepotism—a friend of a friend of my father was responsible for hiring there, so a word in the right ear got me a summer of freedom from nagging little brothers and nosy parents and trying to hustle jobs despite the fact that I was just a hair too young to get a work permit from the State of California—which had, some time before, decided that no “child” (i.e. teenager) should be “forced” (i.e. allowed) to work a job without the approval of the State, which the State would not grant to anyone too young to drive.

So, I had to settle for this summer camp. Not just any summer camp, but a Christian summer camp.

By “Christian” I don’t just mean “people who like Jesus and pray over their dinner,” I mean Christian in the brand-name sense.

They had a bookstore that sold only books from Christian publishers—our compulsory morning “private devotions” had to be conducted from “workbooks” sold at the store. Our work was regularly reviewed by our bosses to ensure our “spiritual growth.”

They had a policy that we could only listen to music by Christian bands and watch Christian movies—by which they didn’t mean “made by Christians or dealing with religious themes” but “exclusively produced by bands and movies laundered through companies with direct affiliations to the Evangelical lobbying and media industry.”

With a raft of rowdy teenagers on staff, this policy created a good deal of conflict and confusion, particularly in an era when signaling one’s religiosity was a very good business move for pop culture figures (like Mel Gibson, Martin Scorsese, and U2’s Bono).

Though I grew up in the Evangelical world, because of my heritage I had never been fully immersed in Evangelical culture before that point. To be so engulfed at the height of the Satanic Panic was...instructive, to say the least.

Instructive?

Well, despite the very obvious Catholic heritage of the work, it turns out that The Lord of the Rings isn’t a “Christian” book because the good guys use witchcraft. Long before Harry Potter was “promoting Satanism,” Gandalf was providing a “gateway to the occult.” I had no idea! The scandal!

Suffice it to say, I was not a good fit.

My summer reading project that year was The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever by Stephen R. Donaldson. This fantasy epic is a reflection on religion, doubt, grace and sin written by a missionary kid whose relationship with religion is even more complicated than mine. Naturally, I had to endure a (literal) struggle session for having “books about magic” in my dorm room—if it had happened last year, you might’ve thought I gotten caught watching a James Bond movie without a Strong Female Sidekick.

At that age, I was eager to earn churchly brownie points, and I would have fallen right into line had I not spent my younger life surrounded by towering works of beauty—from The Divine Comedy to the paintings of Bouguereau and Michaelangelo and Turner, from the classics to pulp fiction, from Excalibur to Star Wars to Mozart to Leonard Cohen. Yes, I inhabited the same moral straitjacket as my Evangelical fellows, but my love of beauty meant I could never buy the purity-spirals that animated my cultic1 bubble.

With rare exception (such as the better works of Stephen R. Lawhead), nothing the Evangelical world produced could hold a candle to the quality and beauty of even the crassest B-movie on Cinemax.

Naturally, this was because Satan presents himself as a being of light, so one would expect his works to be beautiful beyond description, just as he himself was reputed to be.

Well, that was the explanation that seemed to make sense to everybody else.

It just left one problem:

If God was the author of all goodness in the world, why should that which is good not also be beautiful? Is not beauty also a form of goodness?

Why were my brethren so blind to beauty?

The Transfixing Vision

When taking all media into consideration, the mystery is the most successful story form in American culture. Invented by American writer Edgar Allan Poe in 1841 with The Murders in the Rue Morgue, the genre—in all its thousands of forms—turns on a fairly simple mechanic:

Solve a puzzle, learn a secret truth of the universe, and with this truth your hero has a chance to set the world to rights.

America has always been a chaotic land, and its cultural roots lie in the mind of obsessive people who were addicted to mystery. The mysteries of God, of theology, and of the new wild land across the sea. They fled the orderly life of England in order to build a land of pure devotion in the new world. They did this because they were convinced through their study of Protestant writings that all the great trappings of the Church (in this case, the Church of England, which was basically “English Catholicism without the Pope”) served chiefly to set the eyes of the believer upon the Church instead of on the god the Church was ostensibly serving. Sacred calendars, fasts and feasts, rituals and sacraments, all of these seemed like meaningless rigmarole to a bookish people who believed that no god worth the name would ever hand the power of salvation over to a corruptible corporate institution which dealt in money and land and earthly power.

God should be in charge of salvation, they reasoned, and the community should encourage the practices that brought people into communion with God, and the rest of the whole church thing be damned.

The Puritans—who, as the name implies, wanted to purify the Anglican church of its formality and ritual structure and worldly ties—tried first to go to Amsterdam. Unfortunately, life in seventeenth-century Amsterdam was wild and free and beautiful. Science, art, philosophy, business, and all manner of glorious prosperity-enabled pleasures (music, free mixing of the sexes, fashion, and intellectual debates chief among them) eroded the solidity of the cultic community. In purifying themselves of ritual obligations, the Puritans risked purifying the Calvinism right out of their community.

So, to preserve their vision of becoming an example of godly devotion that would shame the sinful and worldly English Christians, they regrouped and raised money for a crossing to first England, and then to the New World, where they suffered and died horribly for the right to build their community in the inhospitable land called “Massachusetts.”

We call them them “Pilgrims,” and several of that small community were my direct ancestors.

Their writings make instructive reading. They are devoted, in every sentence and line, to seeking out the mysterious will of God and putting it into practice, in order to bring into the world the Kingdom of God and fulfill the divine plan, whereby the damned will see their errors too late, and the anointed will be rewarded for their endurance and faithfulness with an eternity of divine union with the One Who Made All Things.

Though the Puritans were not exactly the anti-sexual, anti-hedonic people we remember them as,2 their relationship with such pleasures was mediated entirely through their anointed vision—anything that did not serve to forward this vision (or worse, had a flavor of anarchy3) invited suspicion, censure, excommunication and, in a few scattered instances, accusations of (and executions for) witchcraft.

The mysteries of God are seductive, and their seduction is baked right into the gospels in dozens of parables and illustrations, but perhaps nowhere moreso than in the Gnostic pronouncement:

“And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.” —John 8:28

This verse is describing a “spiritual experience”; a sense of things suddenly clicking into place. It is the joy of having the world turned on its head and re-make itself according to new understanding. It’s the “ah-hah” of the detective who finds the final piece of the puzzle and explains what really happened.

It is revelation. It is epiphany.

It is one of the most profound experiences a human can have.

And it is the drug that American consciousness has struggled with since the beginning.

While Americans have historically been pragmatists (the “can-do” spirit, the liberal bent towards problem solving, the engineer’s mindset, etc.), they were not born that way—they were forged into that shape by the grand task of building a commercial nation and conquering a continent.

But the American people never lost their addiction to the grand idealistic vision, and that addiction was fed with regular infusions of German and French immigrants (whose cultures are the father and mother of Continental idealism).4

When you fall in love, your attentions get bent around an idealized vision of your beloved. All other potential lovers pall next to the object of your affection, and for a glorious short time (from a few weeks to a few years), your entire consciousness is re-shaped to understand beauty only within the context provided by your all-consuming desire.

As with mating, so too with religion. The vision of heaven, or of justice, or of heaven-on-earth, or of a perfectly formed model system that appears to explain everything through a single lens (like politics, or sin, or money), is enough to so-transfix one’s vision as to inspire total devotion—and totally derange all other perceptions.

Once your eyes are set upon such a transfixing vision, the rest of the beauty in the world grows dim—or, worse, it becomes a sort of temptation that you must obliterate in order to protect the beauty of that singular vision.

The Ways of Warfare and Culture

Culture wars are, at bottom, battles over whose holy vision will win the backing of the State (and, thus, which tribe will have the right to dictate the definitions of terms like “good” and “evil”). If you want to win a culture war, you’re wise to pay attention to three basic techniques for conquest from the worlds of business and geopolitics:

First, you can out-do your enemy on his own turf. Win an election against an incumbent. Kill the fastest gun in the West. Build a better mousetrap. When you beat your enemy at his own game, you obtain genuine pre-eminence. All you gotta worry about is the next guy doing the same thing to you—a fate you can avoid as long as you keep improving on your metaphorical mousetrap. This is the logic of inventors (like Edison) and of conquerors (like Rome, Britain, and Alexander the Great).

Second, you can use the Microsoft strategy: Embrace the expectations and customs of the game space, Extend your control by adding nifty features to the product or the cultural conversation that makes you feel indispensable, and then, once you’ve attracted the emotional (or financial) investment of a critical mass of the public, you Extinguish the opposition by tweaking your product so that nobody else can make a notable contribution unless they first accept your domination and work within your rules. This is the logic of cults—the Christians5 did it to the mystery cults and the Jewish religion, the Mormons and the Muslims did it to the Christians, and the Marxists did it to everyone.

Third, you can position yourself as the antithesis of your opponent. You are the paragon of virtue, while he is an exemplar of corruption and evil. Do this successfully, and the people you’re courting will assume that anything good that comes out of your opponent’s mouth is either a lie or manipulation. It’s the easiest of these three strategies, and the most powerful, too, as it taps into the vast reserves of frustration and entitlement that are present in pretty much everyone, and converts them readily into resentment and hatred.

Extra bonus points, too, if in demonizing your opponent you induce shame in your audience about something they can’t help—like their sexual desire, entertainment preferences, skin color, gender, or culture. Your program offers them an escape from the shame, by giving them someone else to exterminate.

The Gospel of Ugliness

“With soldiers’ stance I aimed my hand at the mongrel dogs who teach

fearing not I’d become my enemy in the instant that I preached.”

—Bob Dylan, My Back Pages

The Puritans of old had their devil: The Catholic and Anglican Churches.

These were pits of corruption, of sumptuous indulgence that served as a beautiful veneer for the money laundering, the sex scandals, the embezzlement, the political intrigue, the power-brokering, and the exploitation of the common people under the guise of doing God’s work.

They, therefore, were everything the Church was not.

They were simple and industrious, rather than sumptuous and indulgent.

They were orderly and disciplined all the time, they did not have raucous festivals and somber fasts. God is eternal, therefore what he wants does not vary, so there were no holidays.6 A diplomatic event or a harvest feast, such as Thanksgiving, was tolerable—a festival like Mardi Gras never would be.

Their discipline was that of righteous moderation, neither indulging in asceticism nor excess, never allowing the tranquility of the normal to be disrupted by extreme emotion (is it any wonder that the witch trials were marked by psychotic public displays of emotion?).

And, above all, they distrusted beauty for its ability to distract one’s attention from God.

Beauty—especially man-made visual and musical beauty—was the tool of the devil. It offered the faithful a shallow substitute for the rewards of heaven. It might tempt them to stray. The proper place of beauty was pedagogical and meditative.

And the Puritans therefore left behind no narrative art (fantasy was a sin, and implied ingratitude for the adequacy of one’s own life), no substantial visual art, no music besides hymns, little poetry beyond the devotional and the private (most poetry which survives was not widely published, and often kept within the family), and very little rhetoric apart from sermons and sports proceedings.

It’s all about the message, about affirming people in their opinions instead of creating visions of beauty.

In their resentment and self-righteousness, they rejected wholesale the beauty that makes a culture vibrant—it is little wonder that the Puritan Yankee subculture is one of the historic hotbeds of hysterical and cultic movements in the modern world. The human longing for beauty and anarchy cannot long be contained by even the holiest of visions.

The Death of Art on the Altar of Goodness

Great works of art have been inspired by Islam, Freemasonry, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Secularism, all forms of paganism, Nihilism, Existentialism, and even Communism. Ideology is part of the human palate, it’s one of the ways humans try to make sense of the world, and it is, in its way, a peculiar (if often twisted) form of beauty. The Lord of the Rings, The Plague, 1984, Huckleberry Finn, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Golden Ass, and Oedipus Rex were all written in service of one ideology or another, yet all of them stand as towering artistic achievements.

How can this be, if ideology is so antithetical to beauty?

Because the authors of these works understood that conflict is part of beauty. The villains in these books are interesting and charismatic, and the heroes are flawed and tragic and often risible, at least at times. Each of these stories gives the devil his due—their authors, in advancing their vision of the world, moved with such confidence that they were able to behave magnanimously towards those parts of the world, or human nature, that they found despicable. They understood that there is no evil without virtue, because evil is not the absence of virtue, but the misapplication of it.

Sauron is strong and crafty and wise. Denathor is noble. Titania is beautiful and generous as well as vain and shallow. Winston is a coward as well as a rebel, and O’Brian is formidable as well as cruel. Oedipus is noble and honest, as well as incestuous (I could go on, but this article is stretching long).

Our world is now starving for such beauty.

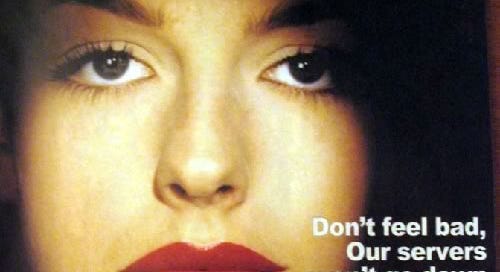

There was a time, not long ago, that you could barely turn a corner without seeing creativity and beauty and provocation in every corner. As late as the mid-2000s, dry tech magazine ads often looked something like this:

Note the multiple levels at play:

There is, of course, the iconic disapproving, unattainable, and beautiful woman. There is the implication that the kinds of tech geeks that read such ads are useless with women and accustomed to rejection. There is the assumption that this stereotype is both true enough and accepted enough that the audience that is the butt of the joke will also laugh at it.

This ad is a work of art. It turns on a great joke, and it has a purpose: to engage the audience with an emotional experience that will make them feel curious about the product in question. It operates at multiple levels, and those levels all focus towards a single point. The are in harmony with one another. The ad is so effective as a work of art that it almost fails as advertising—hundreds of thousands of people loved the joke so much that they can’t even remember the product.

This is how non-musical art works. It renders an idea or an image or an experience in a way that draws the consciousness in because there are multiple symbolic, aesthetic, and cultural elements playing together like notes in a symphony, all harmonizing and creating a new, beautiful order that arrests the audience’s attention.

Music, of course, works the same way, but using sound that need have no linguistic content whatsoever. And dance, the same, but with form and movement.

In all cases, it is the convergence of multiple levels of order upon a single point of harmony.

That ad is from 2007, and it marked the end of an era.

I said earlier that I learned a lot at the summer camp about why my favorite artists were satanic.

This ad is where I, for the first time, truly understood why all other art is problematic. It was, you see, “misogynistic.” It “sexually objectified women.” It made “women feel uncomfortable and unwelcome in tech spaces.” It created “harm.”

A new vision of heaven had dawned. Gandalf was no longer a gateway drug to Satanism—but sex differences (of any sort) were now a gateway drug to rape culture, which was a gateway to inequality, which was a gateway to dehumanization, which was a gateway to “genocide.”

The new religion has found its place. It brooks no ambiguity. It must have doctrinal compliance. The purpose of art is to spread its gospel—any art which does not is creating a fertile ground for enemies to gather. Just as Christians of different denominations have often been “demonic” and “satanic” to one another, so to now are civil rights heroes “white supremacists” and other such things because they dare to discuss or imagine things that lie outside the purview of the religion.

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

Bow the knee and tremble before the might of the vision of absolute equality, absolute community, and absolute tranquility.

Be untroubled, brother, by the disruptions of beauty, the pains of this life. Put your trust in the gospel, and all will be well.

The human love of beauty is our true enemy.

Because it shows how shallow our salvation is.

If you found this essay helpful or interesting, you may enjoy the Reconnecting with History installment on Understanding Before Thinking, and this essay on learning to think through language and story: Are You Fluent in English?

When not haunting your substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. You can find everything currently in print here, and if you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

The borders between “Cults” and “Religions” are permeable and ever-shifting. The “cultic,” on the other hand, is that which characterizes the theological and ritual world inside the religious community, be it a church or an apocalyptic suicide pact.

They actually left behind some interesting, if restrained, erotic poetry, were top notch brewers, and were great lovers of tobacco and food.

That is, it was primal and difficult to govern with the rational mind.

“Idealism” is the moral preferencing of the ideal over the real. German philosophy beginning with the Protestant reformation is heavily idealistic, and French philosophy picked up the German baton and ran int into the End Zone with the French Revolution. Notable idealists include:

Calvin, Hegel, Luther, Heidegger, Rousseau, and Sartre.

All these great religions started out as cults. Their endurance allowed them to develop into full-fledged religions over time.

Literally: “holy-days”

While quite insightful, I feel the end conclusion goes too simplistic. There are multiple "new religions" arising these days and not just that based on sex differences that you cite. For example, we're seeing the rise of "can't criticize the goodness of white people" in certain states of the union. A backlash, perhaps, but with much the same religious fever. Not to mention cults of personality, both domestic and abroad.

The relationship between these other "new religions" and beauty has its own complexities perhaps worth exploring. I cannot, for example, forget the story of a friend of mine who worked as a chef. One night a particularly rich "guru" and his sycophants dines there, and the "guru" ordered his steak well done to the point of burnt. Of course, the sycophants immediately all ordered the same, destroying the beauty of a well done meal.

I would argue that all ideologies oppose true beauty, because it goes deeper than the surface thinking that ideologies require. Crass superficiality may be allowed (gold plated tennis shoes?) for social signalling, but something that touches the soul?--never.

Interesting read, but a casual observation has me spinning at a tangent. Like the mystery Poe is the father of American horror which is just as moral a genre as mystery. But where as the former is about the restoring of the moral order, learning the truth and "with this truth your hero has a chance to set the world to rights," horror is the story of " the damned will see their errors too late".

It should not be surprised the same source synthesized both.

But now I'm thinking on my favorite mystery subgenre: detective, which arguably is one point where the two touch. More interesting is I'm noticing when detective stories are written seem to be a strong indicator of if they are mystery, the truth allows the detective to set at least some part of the world right, or horror, where the truth comes too late to save the world.

In film, "The Maltese Falcon" is the former for all the grayness of its ending while "Forget it Jake, it's Chinatown" is the quintessential expression of pointless knowledge of the truth. In books the former runs through Lawrence Block while Dennis Lehane does the latter so well some books made me physically ill. I'm left to wonder if this is a mark of society realizing Nietzche's madman was right.