Please note: This is a long post with many footnotes. It may get cut short by your email service (especially if you’re on gmail). If you have this problem, you may read the full article in your substack client, or at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com

Butch the Bastard

Butch was a criminal, and he liked it that way. He took what he could, when he could. He stole property, he kidnapped children, he raped women, and he’d kill anyone who got in his way. The people in his town knew to give him a wide berth, because he was the biggest, baddest bastard in the whole damn county. There was no higher authority to appeal to—he’d killed the sheriff and nobody would take the job for fear of getting knocked off in turn.

Butch was rich, and he was mean. He succeeded in intimidating everyone because he wasn’t working alone. He had buddies, and they all had wives and kids, and the entire gang came out to support him if he ever got in trouble, because they knew that as long as he was on top, they were protected and got a slice of the spoils.

The only thing any of the ordinary people could do to escape him was to move away (which is what he wanted, because he would take their land when they left). But, of course, if he caught them leaving he’d give them a good solid beating and take the women for himself (at least temporarily), because nobody who was so chicken as to run away deserved anything but contempt.

Nobody would stand up to Butch.

Nobody, that is, until John. When John was already close to breaking, he went to visit his neighbors. There he found that Butch’s gang had raided the place. John saw the damage they wreaked. He urged his neighbors to stand up to Butch. “If we all retaliate together,” he said, “They’ll have to stop. They can’t stand up against all of us.”

But the neighbors were too cowed, and they begged John to stop talking crazy.

Then, upon his return to his own house, John found he’d been burgled, his wife was beaten unconscious, his dog was dead, and his daughter was hiding in the upstairs closet, catatonic with terror, her clothes torn and her legs bloodied.

John decided he’d had enough. After seeing to his family he took his hunting rifle and some road flares, then he made his way to a spot in the woods near Butch’s house. He climbed a tree with a view of both the front and back doors. Knowing that he might be in for a long wait, he settled in for a nap.

Some time later, sounds of drunken carousing jostled him awake. He spotted Butch and a couple of his children and some of his gang retreating into the house. John stole down to the ground and crept toward the shed. He found a can of chainsaw gas and took it, pouring is contents around the front door and the back door of the house, then splashing it over a few other likely spots.

When he was done, he lit the flares and threw them against the house, then retreated to his tree.

The party inside was rocking pretty hard, and nobody seemed to notice the fire for several minutes.

By the time they did, the house was engulfed.

As people broke windows and ran for their lives, John expertly shot every last one of them down.

Then he went home.

When the news came around, John learned that several women who’d been taken prisoner during that day’s raids had died that night, along with Butch and his two brothers, Butch’s four children, his wife, and two of his good friends.

The War of All Against All

This story more-or-less resembles what we’ve been taught to believe about how anarchy and warlord-ism works. The reasons we think this way were formulated during a wrenching period of political chaos and rampant warlordism in early modern England.

Back in the 17th century, English philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote a treatise called Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil1 in which he investigated (with great erudition) the purpose and role of government. It was an important work, written as it was during the second English Civil War and intended to help solve questions of legitimate succession and the division of powers between the people and their sovereign (i.e. government).

It was a blockbuster hit, and formed part of the intellectual background of the United States’ founding brain trust.

Perhaps the most famous passage, and the one that gets butchered as frequently as it is invoked, is where Hobbes advances his fundamental justification for the legitimacy of government. Humans in a “state of nature” (i.e. without the benefits of civilization and an over-arching State) are engaged always in a struggle for resources and supremacy. A state of nature, he argues, is a war of “all against all,” and it is only through the creation and maintenance of sovereign terrifying government (what he calls “a common power to keep men in awe”) that a good life is even possible.

In his own words:

In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth, no navigation nor the use of commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

The logic is pretty compelling. We’ve seen in places like the Soviet Union—or, to a lesser extent, today’s America—how, when people don’t have confidence that they will own the fruits of their labor, they get lazy, they check out, and they stop participating in civic, cultural, and economic life. They drop out, they go on the dole, and the country hollows out from the inside.

Everything good, on Hobbes’s view, derives from the terror that the state instills in the hearts of the anti-social and the criminal...and the everyman. Without a coherent government, you don’t have an idyllic libertarian life, you instead have the rule of Butch from our opening tale.

The strong prey upon the weak, and our only hope is in somehow keeping our system together, because, as we’ve seen across the world in one communist revolution after another—and as you can see in Haiti right now—if the system were to disappear we’d all be under the boot heel of raiders, rape gangs, and psychopaths.

But what about the “goodness of humanity?” Aren’t people basically good, deep down?

This popular dogma originally promulgated in the 18th century by Jean Jacques Rousseau, who popularized the idea of the “noble savage” who lived a peaceful life in a state of nature.2 Most of those places I just alluded to—Haiti, Ecuador, everywhere with a communist revolution—were set up by people who believed that human nature is basically good, and if only it were liberated from monarchy/capitalism/oppression, everything would magically improve. Get rid of the evil structures of society, and people would be decent to one another, and the world (or at least their country) would become a beautiful egalitarian utopia.

Ask the subjects of Mr. Barbecue how that’s working out for them.

A Warlord Taxonomy

War is an occupation older than mankind. It is a regular activity among settled pre-agricultural peoples (usually motivated by wife-stealing) such as the Yanomami in remote corners of the world today. Many of our great epics and legends, such as The Illiad and the Icelandic Sagas and the Arthurian tales, sing the praises (sometimes ironically, in the case of The Illiad) of great warlords who conquered, razed, and built anew. A (highly disputed) percent of Europeans—ranging from 0.5-10%—are descended directly from Genghis Khan (and his army). He was one of history’s most successful warlords, who loved his spoils of war (i.e. women he captured to rape), and who also wiped out around a quarter of the population of the Eastern hemisphere during his campaigns.

We even see the cultural triumph of warlords in the Bible. The Old Testament—in the books of Genesis-through-Joshua—consists of the self-justification and image burnishing of a pastoral (i.e. herding) and raiding culture who preyed upon the city-states and farming tribes that were its neighbors. Then, after that culture became a settled society, it received the same treatment at the hands of its neighbors (the Philistines, the Babylonians, etc., plus several other countries that the Bible doesn’t mention as those conquests had been lost to memory by the time it reached its final form)—related in stories told in the book of Judges and several subsequent volumes. And, if anything, the Bible undersells the uncertainty and brutality of that went on in the Levant during the chaos after the collapse of the Bronze Age empires.

So what is a warlord?

A warlord is a man (almost always) who secures, maintains, and or exercises power through conquering violence.

Warlords rise to fill power vacuums. When they come in from the outside, it is often either because they were displaced from their own native lands for one reason or another3 or because they wish to spread their own culture far and wide to fulfill the terms of a manifest destiny and/or gain political credibility back home (Julius Caesar, Alexander, Napoleon, Alric the Visigoth, Tamerlane), or because they were just really pissed off and wanted revenge, and in taking it they discovered they had a real talent for running an army (Genghis Khan).

Of course, to be successful, warlords must also have a power base (either a gang of supporters they’ve accrued through personal charisma, or a clan, or the sponsorship of a foreign power).

To break it down more further, warlords come in a few basic flavors:

Conquerors—people who wish to gain political control of a piece of geography. Nearly every single country and polity now in existence came into being this way. Immigrant waves are sometimes tools of conquest used either by foreign powers or by domestic elites who fear losing their grip on power, but they are not, strictly speaking, warlords or armies.

Raiders—those who merely wish to steal, rape, enslave, and/or raze. In history, these are usually non-settled peoples like the Tartars, the Mongolians, the early Biblical Hebrews, the Comanche and several of the other Plains Indian tribes, and the Vikings.4

Agents of Chaos—those backed by corporations or governments to create a power vacuum so a third party may later swoop in and save the day. This was a favorite tactic of the US government (with the Westward Expansion), the British Empire, the Roman Empire, the Soviet Union, and a number of other such players throughout history. This includes, but is not limited to, outside funding of minority factions, supporting organized crime, trade delegations, missionaries, mercenaries, and assassins.

Mafia—those who are engaged in business and are primarily concerned with the bottom line. They often find their germ in ghettoized communities which need communal self-defense. The Italian Mafia, the various New York criminal organizations of the 20th century, and the post-war British criminal gangs all started life this way. Once they have achieved dominance as neighborhood order-keepers, they then expand into businesses to fulfill demands that the law either doesn’t allow (porn, weapons, drugs, alcohol, etc.), or that the law controls so tightly that the market can be easily cornered (such as garbage collection, cigarettes, etc.). The Mexican Sinaloa Cartel under El Chapo is a standout recent example of this sort. When El Chapo was taken out, his business was split among his underlings who are mostly members of the next group.

Psychos—those who we reflexively call “Criminals,” but who are actually the subset of criminals that are in the game to satisfy their individual lusts (for revenge, for power, for violence, for sex, etc.). Serial killers, neighborhood bullies, and power-abusing police officers5 tend to be this species.

Fertile Ground for Warlordism

When you look at warlord conditions like those portrayed in ultraviolent television shows and films like A Clockwork Orange, Training Day, Breaking Bad, The Wire, as well as at real life warlord-dominated environments like last-year’s Ecuador, inner city Los Angeles from the 1970s onward, the corporate/labor wars from the 1880s through the 1940s, and 1980s-1990s Colombia and Peru, you may notice that they all share something in common which isn’t obvious at first blush.

All of these cases show a sort of warlordism that we fear—and with good reason. These situations are ones in which the common person has no chance. The criminal classes, the cartels, the mafiosos, the raiding parties, the cops, and the other warlords have decided that it is in their best interests to take from the productive and give to themselves. Through slavery, terror, theft, and tribute, they amass to themselves plenary power on whatever scale they wish to operate, be that scale small and entertainment-based (as in A Clockwork Orange) or to serve grand political or commercial ambitions.

In addition to these legitimate reasons to fear such conditions, we are also trained to fear them, and that training is very deliberate: the terror of this kind of anarchy, as Hobbes pointed out, is the foundation of the power and legitimacy of the state.

But look a little deeper, and you may begin to sense what these situations all have in common:

They are all tolerated, maintained, suborned, and sometimes even commissioned by “legitimate” governmental authorities.

This is why self-described anarchists like Michael Malice argue that an anarchist world would have no problems beyond that which we’re currently experiencing, and further argue that the problems of an anarchist world would be much more soluble without the Federal leviathan stretching its financial and regulatory fingers into everything. The Leviathan itself creates the pockets of anarchy that give rise to warlordism—would its fall really be any worse?

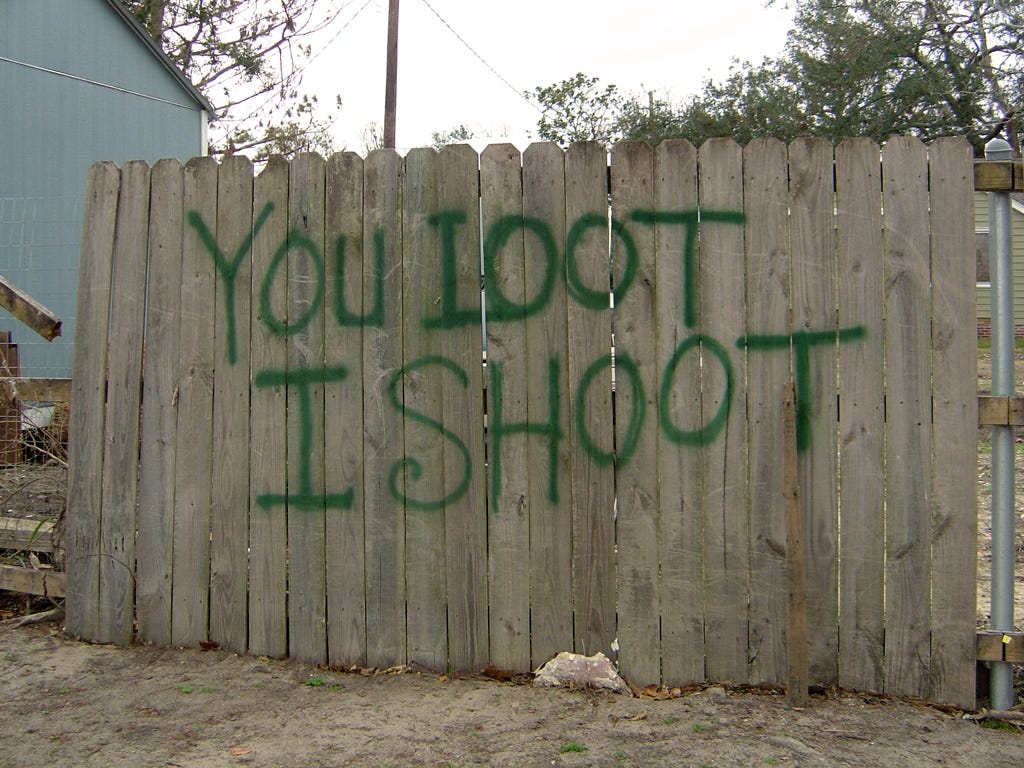

After all, the criminal gangs that terrorize the hoi polloi could not operate if the populace were not prevented from defending itself, either by the restrictions of the law or by being physically disarmed, or both. As detailed recently by Substacker Coleman, gangs do not escape their containment zones without the active assent of the powers-that-be. Criminal anarchy is a direct, and often deliberate, policy end of the State.

We can see quite clearly that this is the case by looking at one of the most infamous eras in our own history:

The Wild West.

We’ve all been told how violent was the Wild West. We’ve heard the tales of Tombstone and Dodge City, we’ve seen endless movies in the era depicting reciprocal waves of vigilante violence. We learned in high school, and we’re reminded by news commentators every time something vaguely anarchic happens, how chaotic and uncongenial and nasty the Wild West was. “It’s the Wild West out there,” is something we hear anytime someone invents a new technology or builds a new business that is not easily and immediately clamped down upon under the existing regulatory frameworks.

Pity, then, that the image we have of the Wild West is a lie.

The West that Wasn’t

As detailed by the historians who actually study the era (rather than merely invoking it for rhetorical purposes), the Wild West wasn’t all that wild. Violent cities (like Dodge City or Tombstone or Deadwood) had very low murder rates—Bat Masterson made his name by clamping down on unacceptable levels of violence totaling a handful of murders and duels over the course of a couple years, none of it targeting people who weren’t “players” (i.e. already involved in longstanding feuds or volatile/criminal enterprises). The violence that did exist—most of it in the form of brawling—was fueled by lonely cattlemen boozing it up and gambling on their off hours. While these antics definitely disturb the peace, fisticuffs and the occasional stabbing taking place in and around a place that caters explicitly to rough customers does not an “era of anarchy”make.6

What was the Wild West really like, and why? We’ll get to that in a bit. But first, it’s worth looking at what happens when shit really does go down, and raiding parties form, and people are left without protection because no authorities can access them.

When Shit Goes Down

We live in an uncommonly fragile civilization. I’ve previously explored, at length, some of the social and geopolitical reasons that our civilization is currently highly fragilized.7 In my next article I’m going to look closely at our technological fragilization and vulnerabilities stemming from it.

The fragility of our current historical moment dictates (to me at least) that it would be wise to consider the risk of warlordism in our midst. We’ve already seen small high-profile instances of this in the CHAZ/CHOP incident in 2020, and less-well-publicized instances of widespread rape and abuse of all sorts at mass movement gatherings such as Occupy Wall Street in 2011. Those who’ve lived in certain urban centers have been subject to rampant, if sporadic, warlordism of the Mafia variety since at least the 1910s. Tribal and corporate warlordism go back to the founding of the United States.

But most of these circumstances arose in the context of a larger more-or-less stable civilization. Conditions of genuine widespread anarchy of the sort which we might expect to provide an opening for rampant warlordism are rare in the United States, with a few notable exceptions.

These exceptions are instructive when it comes to understanding what happens when things fall apart.

When Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast in August of 2005, it knocked out levees and put large swaths of the area under water. Power went down, hundreds of thousands of people over a ninety-thousand square mile area were displaced or otherwise disrupted by the storm. Thousands were stranded on rooftops and in bayous without food, clean water, or other basic survival necessities. The Federal, State, and local disaster responses were abysmal. Those refugees who sheltered in sports stadiums suffered overcrowding, disease outbreaks, and were victimized by criminals also taking shelter.

Most importantly, the National Guard was called out to prevent citizens from entering the disaster zones on wildcat search-and-rescue and aid missions, while governmental efforts were paltry and faltering at best.8

But in this effort, as in so many of their disaster aid efforts, the government was unsuccessful.

Even as raiding and looting parties prowled in the disaster zone, neighbors gathered together on high ground and pooled canned food, camping equipment, and found ways to clean and boil water. Thousands of people snuck past the National Guard in boats and trucks and makeshift rafts to take guns and bottled water and food and diapers to people stranded in the affected zone, and to help evacuate people who had no place to stay because their homes were below the water line. Neighbors, using their own weapons and those illegally supplied by wildcat rescue workers, fended off (and shot and killed) raiders when the raiders approached them. People stranded on roofs risked their lives to pull others out of the water.9

The history of America—and many other countries—is replete with such incidents. When the shit hits the fan, the world does not revert to a Hobbesian hell-state. Instead, it splits four ways.

There are those who wish to prey on the vulnerable, and do.

There are those who, for whatever reason, decide not to put up a fight.

There are those who will go to any length to protect and provide for their own.

And there are those who will literally go up against the military of the most powerful country in the world, putting their freedoms, their fortunes, their lives, and their reputations on the line to protect the vulnerable, including those to whom they have no duty.

No duty except that those people are their countrymen—and their fellow humans.

And most people, in most places, and at most times, fall into these latter two groups.

When shit hits the fan, no matter how incompetent and contemptible is the government response, people pull together. It happened with Katrina. It happened in the big disasters I’ve been caught in (such as the 1989 Loma Prieta quake). It happened at Fukishima and Chernobyl. It happens every time there’s a major wildfire. It happened in the Great Depression, when for years every government measure made things worse, yet in the devastation people banded together and formed economically viable tent cities, opened community soup kitchens to pool food, and those who had the means kept their fraternal orders and benevolent societies alive, which in turn helped their fellows find work and food.

This is what humans do when they have common cause and identity.

It will happen next time there’s a great unraveling.

So much for life without the Leviathan being nasty, brutish, and short.

But there are so many places around the world that seem to tell the opposite story.

What the hell is going on with them?

Natural Warlordism

Once we clear out the cruft—i.e. those states of chaos and warlordism that are suborned or enabled by outside actors to advance economic and geopolitical ends, and wars of conquest—we’re left with a couple of situations in which warlordism does reliably prevail.

First, in clannish contexts. Afghanistan and similar areas are prime examples.

In areas where geography is difficult and central governmental authorities are ineffectual, people must find some way to survive. One of the ways that they do this is along kinship lines.

The history of Afghanistan is very like the tale of the ancestral Hebrews presented in the Bible. As small bands of pastoralists who sometimes also engage in small-scale cash-crop agriculture, the mountain clans have for centuries survived by alternately trading and forming alliances with their neighboring clans, and warring with them. They have, since the time of Alexander the Great, often formed alliances with imperial powers in order to enrich their positions relative to competing clans.

The mountain clans have, like the ancient Hebrews before them, periodically raided and razed one city or another, especially when paid to do so by imperial powers such as the Americans, the Soviets, and the British. And why shouldn’t they? The city people are different people. While Afghanistan is technically a nation-state, it is not a nation in the way we Westerners understand the term. It is a geographic area which is, and always has been, ruled by clans. Those who are inside a clan have claim on its protection. Those who are guests of a clan have claim on its hospitality. Those who are outside the clan are fair game.10

The same dynamic played out for centuries in Northern Europe, and in the Scottish Highlands—clan warfare (such as the infamous feud between the Hatfields and the McCoys) was brought to America by disinherited Scots who migrated across the sea and settled in Appalachia.

While we in the West owe some of our greatest cultural achievements to clannish societies, there’s no denying that living in a clan—especially a closely-bred and heavily-militaristic clan—has its downsides.

The other kind of “natural” warlordism occurs when the neighborhood bully becomes the neighborhood sheriff.

This is the kind of situation we effectively saw in the opening story about Butch and the town he terrorized. It’s not an historical anecdote of any particular town, but it is instead drawn from dozens and dozens of such examples across American and English history. It is so constructed because it reveals how such situations happen: the biggest, meanest motherfucker in town realizes he can get farther with a kind word and a gun than he an with just a kind word, and he doesn’t much care who he has to step on.

In fact, stepping on people is a perk of the job—if not for him, then for his subordinates. A political entrepreneur of this sort who goes solo builds his support base the same way any other wannabe government does: by dividing and conquering. Spot the ambitious-but-lazy among one’s fellows, cut them in on the spoils, and you’ve got yourself an effective little criminal gang.

In a well-ordered macrostate (i.e. anything the size of a city-state or larger), such characters either wind up in jail or they wind up running the jail, depending on their IQ and their ability to pretend normalcy.

But whether such characters are protected by the law or not, this kind of oppression only works when the hoi polloi are willing to knuckle-under to the bully. It takes very little to dissuade such operators, especially early on in their reign of terror before they can build something resembling the machinery of state, and they are, in the end, always vulnerable to assassination.

Just as “natural” warlords come in those two flavors, so too do commoners come in two basic flavors:

Those who fight, and those who submit.

Part of the great appeal of the American Paladin—the lone avenger characters immortalized in American mythology, and not without historical precedent11—is that the leadership and initiative of such people reveal the chinks in the armor of the bullies, as did John in our opening story. Often, the most dangerous of these characters are those who don’t wish to fight, but who get pushed too far. Wyatt Earp and Jeremiah Johnson are but two of dozens and dozens of examples throughout history.

Warlords and the “State of Nature”

Which brings us to the reason that the “Wild West” wasn’t so wild:

The conditions of the American frontier closely mirrored the ancestral conditions of Northern Europe. People needed each other to survive, and—given the need to hunt and to slaughter livestock, the dangers presented by Indians, large predators,12 and the occasional criminal—everyone was well-armed out of necessity. Thus, everyone was forced to deal with their neighbors as if they were people who were capable of violence.

Neighbors who exploited their fellows were liable to get shot, while those who banded together for defense against Indians, carpetbaggers, and industrialists survived and thrived. When someone violated the peace of the town, rustled cattle, or committed violence outside of mutual combat (dueling or brawling), the town banded together to punish them. Community members elected sheriffs, and sheriffs depended on the men in town to serve in posses to apprehend bandits and criminals. When a criminal escaped jurisdiction, a bounty would issue. The enforcement mechanisms went all the way down, and the result was—contrary to the PR—one of the more peaceful periods in American history (Indian wars aside).

It was in this context that women in America first got the vote. As was true in the Viking world of old, a world where women are both physically and legally capable of defending themselves (and were socially expected to do so), and who are vital to the survival of not just children but to the community as a whole, is one where women enjoy full franchise without needing much in the way of political feminism.13

It’s easy to have a poor opinion of your fellow humans when you live in a system that’s designed to promote the most venial, incompetent, self-serving fuckwits at the expense of the competent, the public-spirited, etc.

We’ve lived under such a system for a long time. Our system is designed and propagandized by intellectuals who often find ways to rationalize their frustration with their less gifted fellows by imagining that raw-horsepower intelligence is the legitimizing factor in who gets to rule.

As Nassim Taleb is so fond of pointing out (and demonstrating through his online behavior), intellectuals, despite their many gifts and the immense value they sometimes create, are often idiots.

Power, Tyranny, and Liberty

Political power is always and everywhere an exercise in violence. The difference between tyranny—whether that tyranny is petty or grand—and liberty is found always in who is willing to use violence in defense of their interests. When it’s a warlord, you get tyranny. When empowered (i.e. armed and resolute) individuals band together in communities for mutual protection, you get some flavor of liberty.

The debate over human nature and liberty since the 17th century has been broadly characterized by liberal political theorists as an argument between Hobbes and Rousseau. In the state of nature, are humans nasty and grasping, or are they kind and benevolent?

The premise of this debate is wrong.

Humans are a social species, and we are a predatory species. We depend on each other for protection, procreation, companionship, and sustenance. We also exhibit hostility towards the out-group, and when we are faced with a power vacuum, we will fill it.

Humans always exist in societies. Those societies always have methods of enforcing their contracts, and customs for dictating what is expected of its members, and they always have arrangements for self and community defense.

In other words, Hobbes and Rousseau were arguing over something that does not exist. There is no “state of nature” that excludes “society.” So-called “spontaneous” political order is not a magical get-out-of-rhetoric free card that political anarchists play—like spontaneous order in nature and in economies, it’s a baked-in consequence of the human organism. That spontaneous order, ironically, always includes governing mechanisms, even when it does not include “government” itself.14

If you want some very good (and historically justifiable) depictions of communities in the aftermath of disasters, skip survival porn like The Walking Dead. Stories like this are not about what happens after a disaster, they’re allegories for what’s happening now that are designed to let the audience let off steam and enjoy a little shot of safe contempt and resentment for their neighbors. Instead, check out the 2006 television series Jericho and the 1997 film The Postman.15

So if really bad shit goes down in your corner of the world, what should you expect?

That depends on your neighborhood, and especially on how the people within that neighborhood identify.

People who share some kind of strong identification point, no matter how subtle, are very likely to pull together in a disaster. When a locality has one over-riding such identification point (i.e. “Down deep, we’re all Texans/Americans/from this small town/members of X ethnic group/members of Y religion/part of Z political tribe”), the locality will arrange itself around that identification point. Since everywhere (at least in the US) is vulnerable to civilization-disrupting natural disasters (let alone political-economic disasters), it is wise, when choosing a place to live, to bear in mind the question: “How do the people here really see themselves in relation to their locality?”

Just be sure not to mistake internal community factionalism for actual community fragility. Every family has it’s rivalries, but some of the most fractious and unhealthy families will often pull together to face a threat from outside.

So choose wisely next time you move. When the shit hits the fan, it matters what kind of community you live in.

We will explore what to expect if the shit ever really does hit the fan in the next essay.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also want to check out my Unfolding the World series, a history of the current geopolitical storm rocking our world, its roots, and its possible outcomes.

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. You can find everything currently in print here, and if you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

This is a big part of how I make my living. If you’re finding these articles valuable, please kick some cash into the offering plate!

Archaic spellings in the original.

There is a good argument to be made that Rousseau was writing satirically. I’m not enough of an expert on Rousseau to hold a firm opinion on the topic. For the purposes of the history of thought, his influence is the same as if he was not writing satirically, so the controversy is not worth exploring in depth here.

The Sea Peoples—remembered in the Bible as Philistines—seem to have been pushed out of Gaul by climactic conditions and/or volcanism. The waves of peoples who became the Americans were pushed out of their native lands because they were politically and religiously non-conforming, or economically inconvenient, or fleeing the Napoleonic wars,

The Vikings (or, as they are more properly called, the Norsemen) are a partial exception to this rule—they had a settled society, but the women controlled the violence within their societies by sending their husbands out “Viking” (i.e. raiding).

I added the qualifier “power-abusing” under protest at the insistence of the beta reader.

In addition to reasons for the propagation of the mythic version of The Wild West discussed later in the article, there are two other factors that deserve pointing out. The first is that The Wild West is a mythopoetic era similar to the early Bronze Age for reasons I discuss in my Every Day Novelist episode called “What’s the Deal With Westerns?”

The second is that it was an era of yellow journalism and “true story” thrillers. Tales of violence and adventure on the frontier sold newspapers and helped create the American publishing industry. The truth of these accounts was strictly incidental to the economic and entertainment value they provided—notorious bandits such as Billy the Kid were invariably far less violent than their reputations. This part of the era is wonderfully epitomized by the relationship between the characters of English Bob, Little Bill, and W.W. Beauchamp in the Clint Eastwood film Unforgiven.

For a quick catch-up, check out the following links to relevant articles: When the Stars Lose Their Sparkle. A Brief, Bright Fire in the Dark, A Simple Moment of Weakness, The Year that Never Happened, and the Geopolitics series.

A reader who has worked in the disaster aid industry added his 2c to this part. It’s must-read stuff, and almost a mini-article in itself. Check it out by clicking here.

It should go without saying that under such circumstances, not every account of an instance of such defense, nor every post-hoc claim of unjustified violence, should be trusted. The Danish documentary Welcome to New Orleans attempts to make the case that the neighborhood vigilante squad that policed the border of the Algiers Point neighborhood in New Orleans did so out of racial animus and without provocation. It makes for interesting viewing, and when I listen to the included interviews carefully I find myself unable to make a judgement about who is telling the truth (and, consequently, whether I would have considered any of the shootings justified under the circumstances). What I was impressed by when watching the documentary is that the vigilante squad was defending the borders of their neighborhood against outsiders, which is exactly the kind of behavior that, as we shall see, history should lead us to expect in situations of temporary—or permanent—civilizational collapse. In such a situation, the default prejudicial suspicion of the outsider is the first line of defense against warlords and raiders.

This is spectacularly oversimplified, but it’s enough for our purposes here.

The roaming avenger is an old character in Western literature, showing up many times throughout the tradition stretching back to Sumeria. Its previous most popular incarnation, before the American Paladin, was the roving knight of the Arthruian and medieval romantic traditions. Later on the figure was re-imagined as the private detective (Philip Marlowe, Travis McGee, and my own Clarke Lantham), two of whom—Bruce Wayne and Lamont Cranston—served as the template for a peculiar subspecies of superhero (Batman, The Green Hornet, The Shadow, The Red Panda, etc.).

If you’re from Europe, I can’t emphasize this aspect enough. The American West is filled to bursting with the kinds of monsters and megafauna that your ancestors on the European Continent and in the British aisles annihilated long ago: mountain lions, venomous snakes, wolves the size of the mythic Dire Wolf, coyotes who hunt in packs, bison, bighorn sheep, moose, and more. The only dangerous animals you have that are analogous to ours are boars and brown bears (which we also have). Most of the above monsters live on or migrate through my property—they pose a danger even now.

There was a suffrage movement in South Dakota, but it was briefer and less opposed than pretty much anywhere else in the Western world, because women had already been voting in school board elections and other matters of local concern in many towns almost since the territory opened. You can get the quickie Wikipedia history (with the usual caveats) here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women's_suffrage_in_South_Dakota

This is where political anarchists go a little off the rails in their totalizing rhetoric—those who aren’t communist Utopians aren’t really “anarchists” at all. After extensive reading of their work, I’ve become convinced that they don’t believe in “no government”—they believe in “no state” or at least “no nation-state.” Instead, they put their chips in the “small-scale community” and “decentralized city-state” boxes on the betting table, which properly makes them “localists” with a libertarian bent, rather than “anarchists.” Alas, in a world of political shouting in online spaces (and everywhere else), those words aren’t nearly as sexy as “anarchist.”

The film is far superior to the 1985 fix-up novel by David Brin upon which it was based. The book’s first half is an interesting exploration of post-apocalyptic communities—its second half is a rather idiotically-written political screed whose targets have largely fallen out of collective memory. But, as with everything artistic, your mileage may vary.

Your point about citizen “self-help” is spot-on; sadly, government is often the greatest impediment to citizens helping fellow citizens. The most frustrating experience of my twenty + years in emergency management was the debilitating persistence of disaster mythology about citizen/survivor behavior. Allow me to explain — I think it reinforces your point.

Perhaps the two most pernicious myths center on the misplaced expectations of authorities, and on information sharing. First, authorities mistakenly expect chaos and antisocial behavior, which breeds mistrust of mass citizen activity. But citizens/survivors do not exhibit mythological disaster behaviors (e.g., panic or looting). Minor instances of scavenging or opportunistic theft draw disproportionate attention, when in fact the vast majority of citizens/survivors act rationally and altruistically, and accomplish much of their life-saving and care-giving while response institutions are still kick-starting their own efforts. Passivity is almost nonexistent. Massive citizen action – “the ‘mass assault' of collective response” always occurs in catastrophic disasters. In disaster after disaster, research and experience — worldwide — prove that the mass actions of citizens/survivors provide more initial sheltering, feeding, and relief, and save more lives, perform more rescues, and transport more injured than first responders. Second, authorities often limit information sharing due to mistaken beliefs of inciting panic. Detailed and specific information that helps citizens to make informed decisions does not cause panic as commonly thought by many authorities, while ambiguous information, intended to prevent panic, causes uncertainty and actually has the opposite effect. “Elite panic” is often common in the ranks of government; panic is a rarity in the citizenry.

Government authorities overlook or discount the mass actions of citizens/survivors because they envision them as passive recipients of services, not as autonomous actors. Official plans are blind to self-help. Although researchers recommend that plans be based on what people naturally tend to do in disasters, plans are chiefly developed with (government) partners and in the traditional way (based on the exercise of directive control by government institutions). They are based on unrealistic expectations about public behavior before and during a catastrophe. Planning that doesn’t anticipate citizens/survivors mass action only accounts for a fraction of a Nation's capacity and is deficient in adapting to emerging realities and lacks the agility to combine and leverage actions.

Spontaneous community organization is local in nature, and will have had little or no interaction with the formalized machinery of response. The majority of people will not have participated in government-encouraged pre-incident preparedness and planning (the government’s own surveys show the limits of stimulating pre-incident preparedness). And they will execute their actions without seeking direction from a centralized decision-making authority—yet are pursuing the same goals as emergency response and public safety (i.e., to stabilize the situation and provide immediate aid to their fellow citizens/survivors). (One of the finest examples of emergent response can be found in Michelle Sollicito’s “Snowed Out Atlanta: The Inside Story of the Fastest-growing Group in Facebook History.” It recounts her extraordinarily successful effort to mobilize a 50,000-strong emergent response group to bail out a city, county, and State’s faltering response to a severe ice/snow storm.) Mass citizens/survivors action like her’s is, in essence, a form of swarming. It attacks and blankets a problem (consequences) from many directions with speed, flexibility, and convergence. It is autonomous, opportunistic, exhibits self-organizing behavior, provides a form of integrated surveillance and situational awareness (e.g., citizen reporting), and can be quickly netted through social media networks (e.g., crowdsourcing). It relies on basic rules of operation, is fluid and shifting, has no centralized control, yet contributes to achieving the effects desired by the formal response structure (stabilizing the situation).

The failure of formal systems to respond effectively in the immediate aftermath of a catastrophe is predictable. Directive control and centralized decision-making will falter. Conditions will deny or hinder organized access to the affected area for a protracted period. The scope of need will exceed the capacity of the traditional response framework and its institutions. Authorities will not have the means to intervene quickly, will not have sufficient resources to meet immediate demand, and will face extraordinary obstacles in delivering capabilities. Citizens/survivors are master improvisers by necessity, and their collective actions compensate in great part for the required startup time, and possible failures, of the formal response system. We need to rethink our networks, hierarchies, and complex rules and instructions that currently present impediments to cooperation. Preparation and improvisation must be synchronized.

It may be a forlorn hope, but it’s time to move from a government-centric approach to a hybrid that combines governments' capabilities with grassroots collective intelligence (e.g., citizen reporting) and collective action/response (e.g., crowdsourcing). The ability to quickly turn information and knowledge into mass action is increasing every day, and is the impetus for explicitly addressing the role of emergent response groups. How would we go about this transformation?

Government could identify physical, virtual and other enablers/force multipliers that can assist or augment citizens/survivors' mass response actions, and embed their use and provision in its capabilities and plans (e.g., the means to provide all-channels communication with swarming networks of citizens/survivors)

Government could commit to eliminating bottlenecks and impediments to cooperation between citizens/survivors groups and responders and response organizations.

Government could incorporate the contributions of citizens/survivors to stabilizing the situation in an agile planning system, which would contribute to superior shared situational awareness (e.g., real-time information sharing), self-organizing simultaneity, and the achievement of shared ends (e.g., stabilization of the situation and deliberate transition to formal, sustained disaster programs and services).

Government could establish the means to quickly support creative contributions that were not envisioned in pre-incident planning, to establish close cooperation between emergency services and citizens/survivors groups, and adopt a ‘disclosure imperative' by disclosing/sharing information, plans, objectives, goals and needs during the catastrophe so that government, nonprofit, and citizens/survivors collective actions can achieve shared ends (e.g., stabilize the situation).

Government could promote and adopt advances in information structuring and processing that support rapid disclosure and information sharing, including tools such as crowdsourcing to provide robust capability to assimilate the dense “tsunami” functional information (e.g., citizen reporting).

The government could identify stabilization criteria and share it widely.

The government could privilege heroic response actions of citizens/survivors over those of responders in word and deed and tell the story over and over again. Response professionals have adopted emergency response and public safety as a profession, whereas citizens/survivors accept danger and risk on the spot, and creative coping is their norm.

Finally, government could reignite the role of leadership in: - Inspiring individuals and groups to action - Identifying/indicating appropriate priorities and methods; setting priorities and sequencing actions that best support citizens/survivors mass response actions that contribute to incident stabilization - Clarifying purpose - Preserving faith and hope - Removing interference and impediments to cooperation - and encouraging solidarity and mutual respect. An Israeli Prime Minister once described unity and resilience with respect to sharing responsibility as “sixty percent my responsibility, and forty percent the public's”. I think the percentage skews heavily the other way, but it makes your and my points.

Well written and argued. Comports with much of my life experience living here in these united States and abroad. There are another three factors not mentioned here that are worth considering, IMO, for your thesis.

Even in places where it's tribal (like Afghanistan, where I lived for some 14 months), there are checks and balances on violence. Some tribes, like the Kuchi, are nomadic, while other tribes (Zadran) are settled farmers, and still other tribes (Mangal) are mountain people.

1. No one from any of those tribes would feel free to just go out and randomly attack another tribe's members without a very good justification and NOT just because of the possibility of reprisal, but because of what *their own tribe* and leaders might due to someone who initiated "unauthorized" violence that might bring reprisals onto innocent members of the tribe.

In other words, even in Hobbes' claimed "state of nature" where life really is nasty, brutish, and short, it's not *that* nasty.

2. There are frequently limitations on violence imposed by weather and geography. Afghanistan's mountains and winters basically shut down violence of any kind by October. Once the snows close the passes, everyone hunkers down and we'll pick up our feud in the Spring. Maybe...

3. Without government to direct large-scale economies, weapons and ammo are extremely limited, usually to small arms. It's hard to make "violence" on the kind of scale that wipes out entire villages or peoples without national economies that fund large standing armies people by people trained for killing directed by people willing to do so.

These kinds of inherent limitations on violence are ALWAYS ignored by Statists in justifying their claim for the absolute need of the biggest gang and cartel of all - government.

Just wanted to add that for your consideration.