Nine months ago, I was rushed to surgery with a life-threatening condition—you can read about the whole (strangely amusing) adventure in my essay Healthy Living Can Be Deadly.

Well, two surgeries, really.

After the second surgery, I asked for pain meds to be withheld until after I’d tried to sleep through the night. Weird request, but I had my reasons:

When I was five years old, I suffered a high fall onto my head, leaving me with a concussion and compression trauma to my neck. Since then, I’ve been subject to cluster headaches. I have a gene that renders me relatively insensitive to painkillers (I don’t respond to them until the dosage levels are dangerously high), so I learned to manage my pain by preventing it. To do that, I have to carefully monitor the types of minor aches and muscle tension going on in my body—a particular cascade of aches always precedes the onset of a cluster, and if I catch them early enough I can usually prevent the headache.

After the surgery, I wanted to get a bead on how my body was reacting to all the excitement.

The next morning, I woke up to feel a feeling I couldn’t remember ever feeling before:

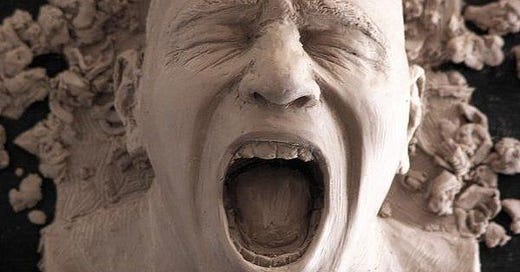

“No pain.”

Though I hadn’t known it until that moment, I hadn’t felt a simple absence of pain in almost forty years. My entire life, my every waking moment had been filled with a dull, constant, buzzing ache caused by the organ failure that had finally put me in the hospital. This condition I never knew I had had formed the baseline for my conscious awareness since before puberty. It was so constant that I’d tuned it out the way that you tune out the whirring sound your tires make when you drive down the highway.

And now, for the first time I could remember, I had no pain.

The Meaning of Pain

I’ve been through enough wild, life-altering events—and seen others through them—to know that no matter how bad or good something is, the effects of it usually pass and the person who had the experience goes on being more-or-less the same person they were before.

Humans don’t change much, at least not quickly. They certainly don’t change without effort.

So my expectation of going from being “Sir Dan the Chronically Inflamed” to “Sir Dan of the Painless Body” was that I would have a little more energy, and need a little less sleep, and be generally a little less grumpy all around.

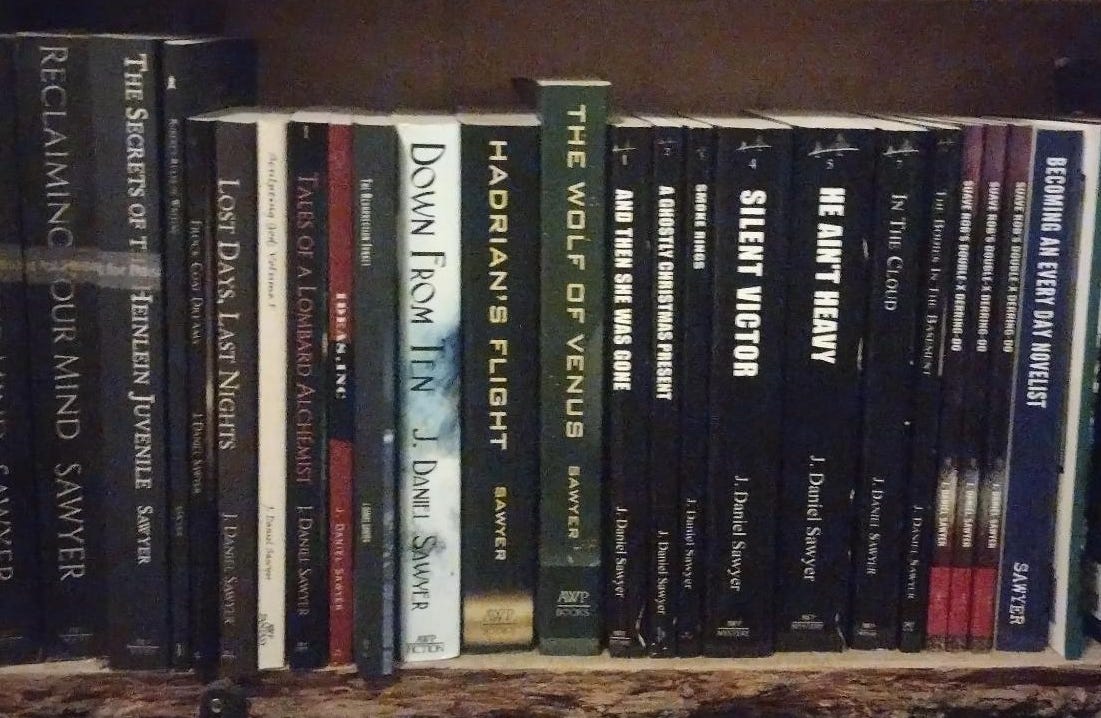

I went home from the hospital and looked at the shelf of paperbacks I made (both the shelf and the paperbacks), looked around at the buildings I’d kinda-built over the previous two years, and walked the trails I’d been hiking, and thought “Huh! If I did all that while I was in that much pain, I’m gonna really kick some ass this year when I’m not in pain!”

Oh, if only I had known!

A Real Pain in the Neck

If you’re a regular reader of this column, or of my fiction, you may have picked up that I am an unusually restless and driven person. Several times over the years, I’ve found myself in the midst of a life that worked pretty well, but that had hit a minor speed bump. Instead of automatically taking my lumps and making a fix and carrying on, I’ve often used such occasions to sit down and ask myself:

“Life moves pretty fast. Are you sure this is what you want to do with whatever is left of it?”

Invariably, the answer has always been “yes” to some things in my life and “no” to others. I’ve gotten very good at saying “no” to good things that I know I won’t be willing to honor with sufficient effort.

Instead, I’ve moved from one side of the country to the other, taking endless side quests on my way to the life I’ve wanted since I was a little kid. I made movies, wrote dozens of books, ran businesses, hosted podcasts, apprenticed in a number of trades, and generally had a good time.

And, every step along the way, people would look at me and ask “How are you not exhausted?”

I would answer honestly, “I’m way behind. I’m slacking off. I’ve got a lot further to go, and I’m not doing half of what I need to do to get there.”

Not that I didn’t know how to relax and have fun—I did. I just relaxed intensely.

That was the most common adjective I heard from those around me:

Intense.

In grade school, I was an intense boy. “It’s why he has trouble with the other children,” the teachers would say, “He’s so intense he threatens them, so they gang up on him.”

I was intense in high school, too. If I got into a conversation, my interlocutor and I might talk for two or three days straight and go without sleep in the bargain. If I went adventuring, it didn’t matter if I sucked or ruled at whatever-I-was-doing, I was intensely focused on it.

At work, back when I worked day jobs, I was told by managers that I was too intense, I was unbalancing the company workflow, and I needed to chill out. But I couldn’t—I was getting paid to be there, I needed to do the job and do it well so that, when I left, I didn’t bring the job home with me.

Even last year, when my body was shutting down, I was building buildings from wood I’d milled from trees I’d felled and dragged to the little bandsaw mill. I was plowing the snow (which sometimes falls in ten-inch batches) from a mile-long dirt road with a hand plow. I felt like I was killing myself, but when I set foot out the door in the morning it was on.

I wrote four hundred thousand words and hosted a daily podcast in that last year when my body was shutting down. Hell, if I didn’t know better, I’d have thought I was on meth.

Except that I’ve always been this way, so much so that when I got a dutch shepherd puppy (a notoriously difficult breed) who needed five hours of running every day so that she wouldn’t eat the furniture, I felt relieved—here was a creature who understood me.1

Then I came home from the hospital last year.

And there was no pain.

And everything just…stopped.

The Son of Sybock

When I was doing my psych master’s, one of the case studies we were assigned was of a woman who had been a high-powered accountant at a Fortune 500 company in Menlo Park. She came in to address the class after we read her file, and were treated to the tale of how she’d presented to her therapist with pervasive anxiety as a result of growing up in a home with an alcoholic parent and an enabling parent, the pair of whom made for an environment that rarely lacked for affection but always lacked for stability.

As the result of her diligence, she worked her emotional problems out—a fact which was driven home to her when, suddenly, she discovered that she couldn’t do her job anymore.

No, I don’t mean “she couldn’t deal with bullshit office politics,” or “she wasn’t interested in a respectable career path and regretted becoming a professional instead of having a family.”

I mean “She showed up to work one day and discovered that she couldn’t remember how to do subtraction.”

Unbeknownst to her, her anxiety from growing up in such an unstable world had pushed her to a career where everything was certain. By her mid-thirties she held one of the top corporate accounting jobs on the planet because, though she didn’t realize it, she found that the numbers made her world calm. She could set the accounts of this vast corporation in order, and in doing so she subconsciously reassured herself that the world was, indeed, an orderly place, and her anxieties were mere affectations; bad mental habits that one could re-train with a bit of psychoanalysis.

But her therapist was not a psychoanalyst, he was into psychodynamics, and he took a psychodynamic approach to her anxiety with an eye towards helping her cure it without drugs.

When it worked, she found out that her entire adult life had been one long exercise in self-medication. She wasn’t upset about this, but she was baffled. She laughed as she cashed in fifteen years of accumulated vacation time and hoped to hell she could figure out how to make math work again by the time she came back.

She didn’t. By the time she presented to my class, ten years after the fact, she still hadn’t found the patience to do anyone’s accounts—to the point where she employed an accountant to keep her household books. She found a new career path, one better suited to the version of her that wasn’t plagued by anxiety.

As a young man in my early twenties, I took note: if I didn’t want my subconscious to throw a monkey in my wrench halfway through my life, I’d better get my shit in order now. I’d better know myself well, and my issues. I had to get to the bottom of my anger problems and my flakiness and my insecurity—and not just by making good on promises and practicing self-control and earning my own self-respect. I was going to grow, dammit, and no subconscious monsters were gonna screw up my life by grabbing me by the hair in middle-age.

I’ve known a few people since then whose journey was very like that of the accountant. When you go seeking enlightenment, you should be careful what you wish for.

The ability to sense and to heal people’s traumas—or at least relieve the pain they cause—is one of the great secrets of cult leaders, who have an instinctive (or studied) grasp of how the subconscious shapes a person’s desire patterns. They bring pain relief—and sometimes real healing—to their victims’ lives and then step into the gap to fulfill the subject’s more genuine desires as those desires become intelligible to the subject.

In Star Trek V, a Vulcan faith-healer named Sybok brings genuine psychic healing to members of the Enterprise crew and foments a mutiny as the crew’s gratitude towards Sybok lead them to follow him instead of Captain Kirk.

After giving Spock and McCoy a taste of his healing power, he offers Kirk the chance to live without the pain of the grief over his dead son. Kirk rejects this offer, saying:

“The things we carry with us are what make us who we are. I don’t want my pain taken away, I NEED MY PAIN!”

The accountant, and my other friends since who have met the same fate, were not hijacked in their healing by cynical cult leaders, but the loss of their pain changed the meaning of their lives. They didn’t expect it, and in some cases the loss of one kind of pain created a raft of new difficulties, but most of them wound up in a vastly better position than they had been beforehand…eventually.

I was warned by my doctors that it would take a while before I was back up to speed. I needed to take it easy, give my body time to heal. After about three weeks, I could start doing things at my normal clip again. By the time two months passed, unless something went wrong, I shouldn’t ever know I’d come within a few hours of complete organ system shutdown. We’d caught things just in time, and once my body healed, I’d be my old ornery self once again.

But what they hadn’t known, and what I didn’t expect, was that after I recovered from my surgery, I discovered that I, too, had become a son of Sybok.

Life Without Pain

Because I live in my body and see things from my own perspective, I didn’t realize how marked the change was. The months after my surgery were very eventful—I had a regular client whose work kept me hopping, I had encounters with large predators and visiting relatives, I was dragging logs uphill with a hand cart, and I kept up with this column. I wasn’t doing as much as I really wanted to, and I was sleeping a lot more than I used to (due to several decades of sleep debt, I assumed), but I was fine. It takes time to recover from that kind of scare, right?

But as the months rolled on, I found that, while I still liked living fast and working hard, down deep I just didn’t care anymore.

If I fell behind on anything that wasn’t a client or personal obligation, I didn’t stress about it. I struggled to do this column—gone were the days when I had two months of essays ready for publication, I was now finishing an article and hitting “publish,” and often missing deadlines by a few days. I let my podcast lapse for months at a time. During the last year before the surgeries I’d lost the ability to write fiction because the pain was so intense, and now that the pain was gone I could write fiction again—better fiction than I was writing before, according to my reading team—but I couldn’t make myself go to the keyboard for it with any regularity. In the second half of the year, I only wrote twenty thousand words of fiction…and I only worked on the fiction for a total of about a week and a half.

I just didn’t give a damn.

I wanted to. I was angry about not caring.

But I didn’t care.

My entire life, I’d lived like the hounds of hell were nipping at my heels, like life could end at any moment and I needed to make the most of it all. My friends and I often joked that this was my theme song:

If you don’t care to listen, the refrain goes like this:

And I ain’t in it for the power

And I ain’t in it for my health

I ain’t in it for the glory of anything at all and I sure ain’t in it for the wealth

But I’m in it till it’s over and I just can’t stop

If you wanna get it done, you gotta do it yourself

And I like my music like I like my life:

Everything Louder Than Everything Else.

Because the hounds of hell were dogging my tracks. My body had been trying to kill itself since I was ten years old, and I could feel the cold fingers of the grave pressing in on me every moment of my life. I faced my mortality regularly, as a form of discipline—staring into the face of death kept me sane.

On the few occasions when I actually was going to die—a fate I escaped in each case through luck, not through my own actions—I was okay with it. I was satisfied. Sure, there was a lot more I wanted to do, but I was checking out on a high, because even in defeat, it was all a high.

Including the quiet moments. The peaceful moments. Silences louder than anything you’ve ever heard.

Everything louder than everything else.

And now, here I was…death was no longer stalking me. My body wasn’t trying to kill me.

So what the hell was I going to do with myself?

When Pain Is The Reason, Purpose is Opium

October was when I realized my new lackadaisical nature was going to bring me trouble if I didn’t figure out how to deal with it. I was sitting on the south ridge watching the sunset in the valley below me. One of my best friends sat by my side.

“Are you okay?” she asked.

“Yeah, I’m great,” I said with a big smile on my face. “Why do you ask?”

“Something’s different about you lately. You’re…chill. I’ve never seen you more relaxed. If you were any more relaxed, you’d be dead.”

I explained how free and easy I felt without the pain.

She gave me a wistful, tear-filled smile aid said: “That might not be good. You’re not intense anymore. You’re never going to do what you want unless you fix that.”

I was six months out from my surgery. I was frustrated that I couldn’t seem to make the magic work anymore. And the fact that she noticed, without me having complained about it, terrified me.

All my life, if you asked me who I was, I had an easy, genuine answer:

“I’m a guy who does what needs doing.”

I always had. And now…well, I still did what needed to be done, but my definition of “need” had gotten a lot more lofty.

I wasn’t in pain. I felt good. And I loved it. I treasured little aches from overwork, I treasured tightness in my back and bruises and burns from lifting heavy things and swinging axes and forging, because the pain was earned, and because it was unusual. It reminded me how much pain I wasn’t in.

But it turns out that physical pain and psychological pain aren’t as different as they seem. They’re drivers—signals that something is wrong and needs to be solved. People in psychological pain collapse from depression when they become convinced that there is no solution to their pain, but short of that, they thrash around in their traps and still do spectacular things (as I’ve documented here). I didn’t really know who I was without it.

I was Captain Kirk.

I needed my pain.

Except I didn’t get to choose not to have it taken away. It was a gift.

Like a lottery win, it was the kind of gift that could destroy my life.

That feeling of death clawing at me that I mentioned earlier? It turns out that it is a classic symptom of organ failure. It’s actually a diagnostic criteria for a number of diseases, including several cancers. When your body’s physical pain isn’t localizable, your brain interprets it as a spiritual sensation: the sense of doom.

There’s a standard and underappreciated riddle in the history of philosophy:

Most of the great (by which I mean “historically important,” rather than “morally good”) philosophers, artists, and conquerors of the Western World had digestive problems. Plato, Nietzsche, Marx, Hegel, Hitler, Martin Luther, John Calvin, Aquinas, Mozart, and countless others struggled with organ pain. I never understood why that should be the case.

Now I do.

When your organs are hurting, you don’t just feel a pain in your belly.

You feel it in your muscles, and in your joints.

You feel it in your eyes, and in your head.

You feel the press of death against your mind.

And you feel it every waking moment, even when you don’t know you’re in pain.

Your very existence is a problem that your mind is trying to solve, but it’s a problem that you can’t solve because it’s not a riddle—it’s organ failure. You feel the press of death because you are dying, however slowly, and you don’t know it. So you search for answers. You long to find a reason. You work your ass off to make the world make sense.

You write books. You contemplate the meaning of life. You try to solve the great problems of philosophy and theology. You build cathedrals. You raise armies and make war.

Had I known that long ago, I might have mentioned it to a doctor…but then that doctor might have figured out what was wrong with me and taken away my pain.

How many books would have gone un-written?

How many relationships that I value more than life itself might have gone un-pursued?

Maybe I never would have made it up here to my mountain hideaway. Maybe I would have stayed my whole life in the suburbs, because they were good-enough.

I had to find something to replace the pain. I had to get my mojo back.

Instead of one reason to do everything (in my case, “Because I must, and I don’t know why”), I’m having to look at the value hierarchy. Absent that unreasoning, overpowering drive that let me—no, forced me to—burn the candle at both ends every day of my life, I now have to focus extra hard on how much I want the results of my efforts. What was once a secondary tool for helping me focus on what to do is now the best tool to remind me why to do it.

It’s still a work-in-progress.

For someone with my personality type, a life of pain, paradoxically, is life on easy-mode. All the groundwork is taken care of. There’s no need to ask why, because that’s never a question in the first place. The sheer drive that the pain prompts is more powerful than all the reasons in the world.

Now that I know that, I’m re-learning how to live fast so that I can die hard.

And the hell of it is, life is more lovely this way.

But it’s a whole hell of a lot more work, too.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I think I need a nap.

If you’re looking for fresh stories, you can find my novels, short stories, visions, and dreams (along with some how-to books and literary studies) by clicking here.

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. If you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

This column is a big part of how I make my living—bigger now due to recent exciting events which you can read about here. Because of this, I’m offering a 20% lifetime discount off the annual subscription rate. If you’re finding these articles valuable, I’d be honored to have you join the ranks of my supporters!’

Read about how I found this remarkable animal in this short series of articles about my quest for the perfect dog: https://jdsawyer.net/articles/dogonomics/

What a story! You’ve caused me to remember Robert Heinlein’s story Waldo. You’re kind of the inverse of Waldo himself. You’re drastically changed as Waldo was, but the gift you received was the gift of relaxation.

For those who don’t know, Waldo had myasthenia gravis and could barely move, and he had a tremendous, hungry intellect and drive to invent. He had to live in orbit so he could move. Spoiler Alert!

An experimental treatment helped Waldo; (you’ll have to read the story to learn how), and his body could then keep up with his restless mind.

I hope you can find a balance between relaxing and working that suits you and helps you live a life you find rewarding. Good luck and warmest wishes.