This is a long one, and might not fit in your email client. You can read the whole essay, without paywall, at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com

Back in my essay Why Must the Anointed Despise Beauty? I had a go at why so-called “message fiction” and other ideologically motivated art is so frequently unsatisfying. That article, while it nails a major cause of the ugliness of our historical moment, leaves something important on the table. Recent rantings by folks here on Substack and out in the wider culture, including in both right wing and left wing artistic circles in which I am involved, have made it clear to me that there is another factor at play that creates some staggering cultural sickness that hurts everyone and everything it touches.

The Smurf Problem

Even though I grew up safely ensconced inside the protective cultural walls of fundamentalist Evangelicalism, I was subjected to massive demonic propaganda. For one thing, my ordained Ph.D. of a father, who is so straight-edge that I was surprised when I learned that he knew the difference between Lysergic Acid Diethylamide and the Latter-Day Saints, had a deep love of rockabilly and psychedelic rock. Anything recorded between Buddy Holly and Pink Floyd was pretty reliably to be found on the turntable. By the time I was six years old, I knew more about hallucinogens and their mind-expanding properties than I knew about the weird kinky shit King Saul made his son-in-law do in order to win his daughter’s hand in marriage (a Biblical story we studied in Sunday School).

And, of course, you can’t learn about hallucinogens from acid rock without learning about the May Queen, the Tree of Life, the Ouroboros, and a few dozen other happy-go-lucky Kaballistic and Hindu mythopoetic tropes—but none of those seemed all that weird to me, given that I knew about the Tree of Knowledge, the Serpent in the Garden, the Healing Caduceus (a Hebrew idol to the god Nehushtan) of the Exodus, and all the other weirdly-fun shit in the oldest parts of the Old Testament.

But the most insidious influences came into our spiritually well-defended home through that demonic static box, that corrupter of innocence, the television. Sprinkled in and among the healthy masculine Adventures of Hercules and Superman, The Wacky Races and Looney Tunes, the most effective demonic propaganda ever unleashed on the American public was worming its way into my affections. This insidious Satanic pablum was intended to destroy monogamy and re-shape the culture of America—through the indoctrination of children—in the image of African tribalist animism, with the primacy of black magic-derived wisdom directing society towards a polyandrous norm, where reproduction was accomplished primarily through enchantment, golems, and blood sacrifice, and where communal dancing was used to keep the people perpetually hypnotized and enslaved to their demonic familiars.

I heard this all in a sermon when I was seven years old, and our pastor was urgently exhorting parents about the dangers of such propaganda. I thought he was crazy at the time, but look around. Notice how uncannily what I just described defines our culture now! I mean, I was an once-earnestly-Christian boy who is now somehow both an atheist and what anyone I was growing up with would call an occultist magician (I do, after all, write fantasy tales where the spiritual valence of magic and demons is decidedly gray). And I watched a lot of The Smurfs.

The Smurfs were designed to convert us all to polyandrous Satan-worshipping African-tribalist animists. My pastor was right, wasn’t he?

Wasn’t he?

Titty-Twisted Sister

Of all the most incredulity-inducing aspects of the ridiculous culture wars of the 1980s, the music censorship wars spurred by Tipper Gore may have been the most risible. Coming in the midst of the Satanic Panic and the Porn Panic (yeah, there was one then, too), it was the Democrat Party’s attempt to pearl-clutch their way to ballot-box success while finding new and creative ways to give the Federal Government direct ideological control over the arts.

For the purposes of this essay, “culture wars” refers to the struggle of different political and social factions for control of the commanding heights of culture: art, public morality, speech, publishing, pop culture, etc.

Groups like Twisted Sister, Iggy Pop, AC/DC, and other metal and hair bands were dragged before Congress to answer for the horrific crime of singing about anger and frustration using metaphors steeped in sex and violence, all backed by hard-pounding, high-energy guitar tracks. These horrible songs were the real reason why child abductions, AIDS, street violence, teenage misbehavior, and rebellious attitudes existed in the first place, and by God these cross-dressing girly-masculine teen-sex-encouraging motherfuckers were gonna pay homage to the all-powerful state, or they’d face the wrath of finger-wagging politicians who all had lower IQs, fewer ethics, and less fashion sense than Dee Snider.

At the same time, across the pond, the UK was having its own troubles with the so-called “Video Nasties,” low-budget genre and arthouse films that weren’t made with mass market appeal in mind, and were therefore more ideologically and mythologically complex, more gory, sexually explicit, twisted, and generally freakish than stuff that might pass muster for late-night viewing on the BBC. Government censorship boards, already in place, were expanded and extended, and lists of contraband compiled, resulting in a very profitable new sideline for Britain’s criminal gangs who were as happy to traffic in video tapes as they were in hard drugs and military weaponry. Between the gay-protogoth New Wave music scene, the IRA’s resurgent activities in southern England, and the amount of interesting and perverse sex you could find in cult sci-fi films out of the local car boot, you could always get access to a good bang in 1980s Great Britain.

If you’re a millennial, you ran into the same thing (on a less intense scale) with filmic and video game “ultraviolence” in the early 2000s, when everybody knew that the only reason anyone would shoot up a school while wearing long dark trench coats was because they liked The Matrix and Nine Inch Nails and violent video games.

Ever since the advent of the printing press, the priggish among us have fretted about the children. Sometimes that fretfulness is genuine, sometimes it’s not, but it is always capitalized upon by political entrepreneurs who see the opportunity to enhance their status by marshaling their resentment against those who are more creative, more personally free, and more successful than they are (not that I’m opinionated or anything). Thomas Bowdler famously, well, Bowdlerized Shakespeare. But whether it happens to “defend Christian values” and “protect children from corruption” or to prevent “cultural degeneracy” and “communist indoctrination,” or to “undo capitalist indoctrination” and “fight white supremacy,” the basic intuition pump is the same:

“Today’s entertainments/customs/ideas introduces the youth to things that we never even dared to imagine as children. It screws up their moral development. It exposes them to ideas they’re not ready for. It robs them of their innocence. And it might even ruin our culture’s mating and dating rituals, threaten our freedom, and erode our social and political fabric. The messages in our fiction are dangerous morally, politically, personally, culturally, and spiritually. We must protect ourselves.”

The Gizzard of Groomers

As I’ve acquired an audience and peer-group of self-styled dissidents from the left, the right, and the disaffected center, I’ve found myself in the catbird seat for watching this kind of thing unfold again in real-time here on Substack and among other writers elsewhere. Porn panics, prostitution panics, family structure panics, sex panics, and demonic panics are again the order of the day. Even those who are not of a religious disposition are becoming alarmed with the amount of occultism and/or aberrant sexuality that is self-evidently going on in the world, from the theatrical to the apparently earnest. The Demon-Haunted World (which, despite Carl Sagan’s lovely book with that title, Sagan himself completely failed to understand) is on the rise again. Times like these are perilous indeed for any civilization, for reasons I outlined in A Time of Magic and St. John and the Beautiful Ones.

Every single day on this platform, I run into writings by people whom I know to be of decent character, many of whom I’ve spoken with face-to-face, whom I know to have good hearts and to be of high intelligence, and yet who are aggressively stoking the flames of a new wave of 80s-style panics about sex, “satanism,” pornography, technology, and “violence.” They do this because they see the decay and ferment all around us, and they—like everybody else in our culture—look around and see that “this thing looks kinda like that thing,” and they draw causal arrows that make complete intuitive sense...but that don’t hold much water.

The worst of it is, they ought to fucking know better...except they oughtn’t, because we live in a cultural end-state brought on by more than a century-and-a-half of the deliberate destruction of our moral reasoning capacity. Among the other problems it creates, it makes us eminently pliable.

Hobbits, Dune, and The Man From Mars

If you’re on the left wing (or once were), a lot of the above is old hat to you. You remember all the stupid fundie censorship wars.

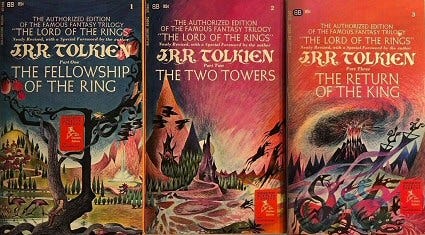

If you’re on the right wing, you may not realize how far back this problem goes amongst your enemies. For example, you might not be familiar with the decidedly mixed reaction that The Lord of the Rings provoked.

Although it is arguably one of the three most culturally influential novels of the mid-20th century (Dune and Stranger in a Strange Land being the other two),1 and while it contributed in major ways to the environmental movement and the Back to the Land movement (as well as virtually creating the entire genre of epic fantasy)2 it also inspired so much hatred that when it was voted the Book of the Century in the 1990s it caused a hell of a controversy among those-who-know-best.

How could a book about Hobbits and magic rings be controversial half a century after its publication?

Who could possibly object to such a book?

Well, conservative religious folks predictably, objected. The positive portrayal of witchcraft (Gandalf IS a Wizard who employs Earth-magic, and Earth-magic of a distinctly Celtic Pagan flavor permeates the world of Middle-Earth) didn’t endear them, nor did the absence of an obvious Christian pantheon, nor did the interracial marriages—no joke, Arwen and Aragorn’s romance was criticized in some quarters as “bestiality” (and worse).

More interesting, though, was how and why the literati, the cultural elites, and a lot of science fiction and fantasy authors objected. For the literati, Tolkien’s work represented the “lowest” form of literature. It wasn’t concerned with everyday life or the struggles and emotional difficulties of ordinary people. It was “romantic” and “escapist” fiction, terms which have been used to morally censure all forms of popular fiction since at least the days of The Stratemeyer Syndicate.3 Such fiction is “corrupting of the public morals” because it distracts people from the problems of “real life” (how times have changed, eh?).

But beneath this dour Victorian attitude there lurked another, much more strident layer of loathing, as articulated to me by several left-wing New Wave authors on late nights when the proof-content of the air was rising to flammable levels:

Tolkien’s fiction endorsed, normalized, legitimized, and valorized anti-liberal, class-based reactionary social norms. Sam is Frodo’s servant, and never stops calling him “Master” and “Mister Frodo.” Feudal lordship is seen as noble. The story marginalizes women and trivializes women’s roles in society and politics, and even denigrates women’s worth as romantic partners when measured against the deep bonds between members of the Fellowship. The good-and-evil division between the white-skinned men of the West and the swarthy servants of Sauron (whether the men or the Orcs) reinforces racist imperialist tropes—note how, while many of these points have come up recently in left wing circles, none are new criticisms. They were part of the attempted cultural assassination of The Lord of the Rings since its earliest publication in the United States. Its popularity was seen, even then, as a threat to continued social progress.

In other words, The Lord of the Rings is under-girded with “offensive” ideas.

Dune has often inspired similar (and louder) vituperation, with the recent movies occasioning much well-published speculation about how/whether Herbert’s series is fascist or Islamist or Imperialist propaganda.

Stranger in a Strange Land is now often demonized for apparent retrograde sexual politics—the opposite of the way its portrayal of female sexual freedom threatened “patriarchal norms” at the time of its release. Other sources of scandal were its anti-monogamist, anti-monotheist, anti-government, and anti-authoritarian themes—different elements offend prigs of different eras, but there’s always something “problematic” going on.

In every single case I’ve named in this article so far, including those bands and books and films I would personally be uncomfortable with a youngster in my charge hearing or seeing or reading, the concerns behind the censorious impulses (including my own) are not just entirely misguided, they are contrary to the maintenance of a healthy mind and culture.

The Blank Slate and the True Believer

Why do fundamentalists happily read their children Bible stories containing genocide, murder, rape, attempted (or successful) sexual extortion, nudism, incest, near-incest, and witchcraft, and then object to any-and-all of these things when they come without the sanction of scripture?

Why do queer activists and some feminist theorists complain that heteronormativity sexually objectifies both girls and boys, eroticizes otherwise-nonsexual human relationships, and indoctrinates children, and yet these same folks are delighted with drag queen performances targeted at kindergartners and with children’s books about gender transitions?

Why do Marxists object to militarism and violence in stories of American patriotism and western history, but glory in tales of bloody revolution against capitalists, western governments, kings, and aristocrats?

Quite obviously, in all cases, it’s because everyone tends to put their own ideological thumbs on the scale: “I will not object to that which offends me if it advances my values.”

They (we?) all do this because all of these culture-groups are operating on a theory of human development that mirrors the old purported Jesuit maxim:

“Give me a child until the age of seven, and I will give you the man.”

In other words, humans are programmable blank slates.

This same view of human nature sits at the root of every totalitarian ideology ever propounded. But if this attitude were true, even to a modest degree, the world we live in would look very different.

The Soviet state would never have eroded from underneath.

The Nazi state would not have been so beset with corruption that it lost the war without being nuked.

Public education would actually work, as would Jesus Camps, fundamentalist churches, and every other manner of cult, ideology, and indoctrination program.

But humans are not blank slates, and they cannot be so easily programmed. Indoctrination simply doesn’t work. Oh, certainly, people will believe (or pretend to believe) that which is expected of them if they are in a world they can navigate, but that’s about all an aspiring despot can reasonably hope for.

If matters were otherwise, there would be no glorious variety of interesting apostates from various religions and political tribes who populate your Substack and new media feeds, or who have filled out the ranks of dissident intellectuals throughout the ages. They would not exist as individuals, and they would have no audience if they did.

I would not be here.

Nor would you.

Humans aren’t blank slates, and thank fuck for that. From intelligence to height to athletic ability to interests to emotional responses, humans are very much themselves, each very different from the next. While all are affected by their experiences, the same experience that can destroy one person will turn another into a hard-hearted pillar of strength, and will turn yet a third into a flexible and sensitive soul.

This is why all totalitarian programs ever attempted have failed. The “true believer” is rare in the world. Every single stupid, destructive, and totalizing moral, religious, and political program in history worked—to the extent that it did—because it gave the adherent a hierarchy to climb, a way to feel important, and a yardstick by which to measure themselves.

This is also why these totalitarian memeplexes always get popular during times of economic difficulty and sociopolitical upheaval.

But it is not upheaval and difficulty itself which so shatters individuals and cultures that religious manias, witch trials, ideological purges, and political purges can burn through. Something else has to happen either before the upheaval, or because of it, to set the monsters loose.

And that “something” is accomplished through a ritual that you—yes you (and me too)—participate in every time you wade into the culture war, forward a moral panic, and concede that yes, in this extraordinary instance, censorship and top-down ideological controls are the right move.

In the Instant That I Preach

In soldier’s stance I aim my hands

At the mongrel dogs who teach

Fearing not I’d become my enemy

In the instant that I preach.

—Bob Dylan, My Back Pages

My friend Gail Carriger and I have long shared delight and bafflement over the audiences our fiction attracts. We both tend to get ideological, demographic, and subcultural mixes neither of us would have expected a priori.

Gail is a proud promoter of “the gay agenda,” yet her comedies-of-manners and YA adventure books have garnered a non-trivial audience among very socially conservative religious women. I’m a universal gadfly who needles all agendas—my fiction touches everything from the darkest possible explorations of pro-natalism, to group marriages, to healthy religious communities, to demon-possessed cats who fiddle with fate, to gonzo Hard SF comedy about the masculine initiation of a transsexual stunt man—and yet I get invited to speak to religious groups and conservative gatherings and I’ve also appeared on any number of very in-the-moment liberal-to-left-wing podcasts.

Each of us writes things that, in a world where “content” (i.e. sex, violence, bad language, controversial themes, etc.) and “ideology” really mattered, we’d be ghettoized in very small market segments that would be easily identifiable from the word “go”...but we’re not.

Because neither of us are actually doing in our fiction what we originally set out to do, or that we still might hope to do.

And this is because, despite all those blank-slatist intuitions about morality and taste, despite how much writers care about the “messages” and “themes” in their fiction, the audience generally doesn’t give a good goddamn. The audience barely even notices these things as long as we’re doing our job right.

Roland Barthes was right: the death of the author is a real phenomenon. Our fictional words don’t ultimately convey the messages or ideas we might want to preach about. Nobody has ever “turned gay” because they got gay indoctrination. Nobody has ever “turned conservative” due to a Tom Clancy or Andrew Klaven novel, or “accepted Jesus” because they read The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe. Authors, artists, and propagandists preach all the time...but nobody who doesn’t already agree them, at least a little bit, is moved by their preachment.4

Preaching, exhortation, messaging, and propagating ideas is not what we do, even though we often think it is.

What we do, unbeknownst to ourselves, is altogether stranger.

The Story and the Dream

What stories do—and I include in this any narrative art, including poetry, music, and symphonies—is not “convey messages.” The medium is not even the message, Marshall Mcluhan’s protestations aside. Instead, what stories do is weave a dreamscape which serves, for the audience, as an arena in which to reason and forge understanding.

If you have read Dune, the world of the book gives you a symbolic arena in which to understand history and politics—from the interpersonal to the international—on a profound level. You may not agree with anything Frank Herbert thought about messiahs, religion, eugenics, artificial intelligence, technology, feudalism, terrorism, ecology, human appetites, homosexuality, or the structure of thought and language, but having access to his dreams gives you an arena to make sense of your own thoughts and experiences.

If you read The Lord of the Rings, even as a modernist who hates everything Tolkien stood for, you have access to a symbolic space for understanding things about friendship, commitment, risk-taking, integrity, and guile that you’d not have otherwise had.

If you watched The Smurfs, you’ve got 101 smurf models (and a few human ones) for how different priorities and personalities might respond to challenges, and a logic built around magic and music for how friendship and loyalty can be made to work between divergent personalities.

And, in all cases, as a child (or as a parent of young children), you have mental vistas for games that allow you to make sense of life.

This is what mythology is, and what it does. It is this—not moralism, or tradition, or theology—that forms that vital part of religion that humans simply cannot do without. The moralists, the traditionalists, the theologians, and the priests attach themselves to the dream. They parasitize it, because its power is vast, and then they try to conquer it so that nobody else can legitimately wield that vast power. But in all cases they are working to denude the dream of its fertility, and when they win out over the dreaming, cultures decay.

In secular nations like The United States, the dream is often a cultural one—we have mythic figures from Davy Crockett to George Washington to Martin Luther King, none of whom are real in an historical sense (despite the fact that they were real people with well-documented biographies), but who nonetheless are more-real-than-real in the dreamscape.

The Enlightenment itself, which we’ve been taught to view as fundamentally irreligious and rationalistic, was fueled entirely by occultism from the beginning. Every single major artistic, scientific, and political figure for the past five hundred years, regardless of their professed religion or lack-thereof, was steeped in a common dreamscape defined by kabbalism, hermeticism, gnosticism, and ancient mythology, usually with a frosting of Christian vocabulary. It was this common dreamscape that fueled both sides of every major cultural conflict since the Black Death: Reformation and Counter-reformation, Enlightenment and Counter-enlightenment, American Pragmatism and French Idealism, Hegelianism and anti-Hegelianism, Internationalism and Nationalism, Localism and Globalism.

And, before that, this common dreamscape was the substrate upon which the medieval world was built.

Denying the Dream

Fixating on the “offensive” visceral or ideological content in a story is akin to attempting to evaluate a painting based on which colors the painter chose to use, often without regards to the painting itself.

The modern—and especially postmodern—tendency to fixate upon such content isn’t merely a distraction; it is the actual problem that spawns all our culture wars. The last two hundred years have seen authorities on all fronts identify the dream-as-such as the problem. Any time you’re encouraged to focus on the “messages” in fiction, on the “content,” on the “ideas,” you’re falling for a ruse that substitutes morality for culture.

Why should this be a problem?

Because morality itself is a fourth-tier reasoning process. It comes after values, which themselves come after mythology, and mythology itself is a dream built out of collective experience. When you primarily engage the world on moral terms (or, worse, political terms), you are doing so because you have abrogated the dream, and the authority of experience upon which the dream is based.

The deliberate attempt to focus the consciousness of the people onto moralism and politics, and to deny the dreamscape, has been underway for at least two hundred years. For reasons ranging from social signaling (i.e. “keeping our women and children ignorant of the ugly parts of life demonstrates our wealth and status.”) to economic (i.e. “an educated man is not a good worker. Workers must instead be trained.”)5 to political (i.e. “the national/international destiny requires ideological solidarity, not diversity of thought”) to medical (i.e. “well-adjusted people have no need for flights of fancy”), the forces that manage and move our cultural world have worked, piece by piece, sometimes by chance and sometimes by design, to remove from us the ability to enter the dreamscape.

We have, in two centuries, moved from Gothic churches and dark communal theaters and books of tales and poetry—all of which require immersion and active dreaming to be interesting—to TikTok videos and TTRPGs and video games, which are not intelligible unless one foregoes dreaming while engaging them (video games and TTRPGs do often require problem solving and creativity, but they are not a dreamscape—they are a gamespace, which is an entirely different animal).

And, in a scant few generations, we have lost the ability to dream.

You can see this inability to dream, ironically, the moment you open your eyes:

Where are the stupidly grand political and engineering and architectural projects?

Where are the foolish experiments in communal living?

Where are the recording artists who are not polished to a spit-shine by the machine?

Where are the new films? The great remakes of old plays and stories?

Who among your friends-under-age-thirty could sit through Lawrence of Arabia, or MacBeth, or could let their hyper-analytical mind’s defenses down long enough to be emotionally disturbed or destroyed by Aronofsky’s The Fountain or Lynch’s Blue Velvet or Kubrick’s 2001 or Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct? There are still some out there—I know a few—but I know many more who, despite very high intelligence, literally can’t shut up for long enough to open themselves to experience without the need to understand and evaluate as-they-go.

Today’s Americans don’t need media literacy training. They don’t even really need critical thinking training (and you have no idea how much it pains me to say that). We’re already entirely too critical and entirely too savvy. And for all our ability to spot propaganda, it hasn’t helped anyone to avoid falling for it.

It can’t.

Propaganda is the art of deception through forming your desires. When someone’s desires are based entirely upon social conventions—like class signaling, religious or other in-group affiliation, politics, and/or morality—those desires are trivially easy to shape.

But as the Medieval Catholic church discovered again and again as it utterly failed to unite Europe, no amount of pressure brought to bear from on high can change the desires of a people who know how to dream for themselves.6

It is thus no coincidence that, in our society, it is the luminaries (the artists, the entrepreneurs, the politicians, the shadowy financiers) who, for both good and ill, still know how to dream and are all familiar with the ancient symbols and thought-forms (i.e. the occult), while the second-tier intellects and the hoi polloi are encouraged always towards the most trivial and Manichean forms of religion and irreligion.

This decay has been a long time in coming.

The existence of culture wars, sex panics, witch hunts, demon-panics, and other such madness is evidence that this project has succeeded in some measure. Their ubiquity and shrillness is evidence that the project is almost complete. Soon, this Brave New World will have no dreamers, save those who are in the thrall of the very powerful.

Every time you try to censor even the most censorship-worthy book, every time you claim your adversaries are demonic, every time you look at someone’s ideology and pronounce it “evil,” you’re giving the game away.

The world does not need culture warriors. There is no culture left to fight for control of.

The world needs culture-builders.

It needs dream-weavers.

And it needs common people who are unafraid to enter even the darkest corners of the dream-world.

It would be unfair to say “without such people, the game is lost.”

It is more accurate to say “without such people, there is no game left to play.”

It is your ability to dream, to dream boldly, to dream darkly, and through that dreaming to make sense of the world, that allows you to hold your own in an uncertain universe.

And it is the ability of children to dream that allows them to orient themselves and to survive as individuals in a world where, under the best circumstances, every adult is telling them who to be, and how to be, and what to be.

No book about sex or gender identity is going to make your child gay, or trans, or slutty. It might, if experienced in the wrong context or without a wider diet of dreams, make them a little more precocious and a little easier to exploit than otherwise.

No book of magick, grimoire, fantasy novel, or demonic tome is going to make your child a Satanist or an occultist.

No book about Jesus is going to make your child a Christian.7

But no books—especially “no dangerous books”—will make your child, and you, prey to all the real monsters that are loose in the world.

In film version of The Neverending Story,8 the black and terrifying wolf G’mork explains to Atreyu the hero why he serves The Nothing, a powerful storm ripping apart the world of human fantasy and killing everything in its path:

“People without dreams are easy to control, and whoever has the control, has the power.”

=== === === === === ===

This article grew out of research into my forthcoming books The Art of Agency: Understanding and Mastering Self-Ownership and The Secrets of the Heinlein Epic, a follow-up to The Secrets of the Heinlein Juvenile my study of the literary origins of the unusual literary structure and aims of young adult literature.

Thank you again for your continued support, which allows me to write articles like this and has recently, literally, saved my life. If you’re not currently a subscriber or supporter, please consider doing so now.

=== === === === === ===

Dune by Frank Herbert had a powerful impact on drug culture, activist culture, environmentalism, and mysticism. Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert A. Heinlein helped shape hippie communalism, free love culture, and the human potential movement.

Both H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard prepared the cultural soil in which Tolkien gardened, at least in terms of audience appetites. The reason that their fiction has proved so uncommonly enduring and powerful is the same reason that Tolkien’s, Herbert’s, and Heinlein’s have. What is this reason? Well, that’s what this essay is leading to. Read on!

Which gave the world Nancy Drew, The Hardy Boys, The Bobsey Twins, Tom Swift, The Boxcar Children, and many more such series.

One of my beta readers pointed out that some forms of literature—such as the works of Ayn Rand—do often seem to move people in radical directions. I discount this for two reasons:

First, such works are not, strictly speaking, fiction. They are parables and philosophical dialogues. Certainly a kind of literature, but not exactly narrative art that induces dreaming. Second, those who latch on to such works are using them as a mirror to explore and articulate intuitions they’ve already partly developed on their own, but haven’t managed to pull into focus.

The exact quote is from John D. Rockafeller, industrialist. Champion and financier of the American public school system. It reads: “I don’t want a nation of thinkers, I want a nation of workers.”

In this case, the “dreams” that frustrated Catholic imperial ambitions were the deep-rooted local pagan cultures and traditions that kept Europe thoroughly balkanized until the Hundred Years’ War finally started the gradual practice of building nation-states out of the previously decentralized and highly contentious world of city-states and village-states and other small principalities.

Most Gen-x kids read Narnia, and loved it, and understood it was a Christian allegory. We are still the biggest apostate generation.

I must confess that I have not yet read the Michael Ende novel upon which it is based.

"It is thus no coincidence that, in our society, it is the luminaries (the artists, the entrepreneurs, the politicians, the shadowy financiers) who, for both good and ill, still know how to dream and are all familiar with the ancient symbols and thought-forms (i.e. the occult)"

I am reminded of the priest character in the Illuminatus trilogy who remarked all religions have their mystics, even the Catholics who keep theirs locked up in insane asylums euphemistically called monasteries.

"No book about Jesus is going to make your child a Christian."

I need to think on this one. While a book alone won't work (as you point out in your footnote) it is stories that engender faith. As a non-apostate GenXer I look back and realize the core of my faith was built not so much on church or doctrine (although questions on the latter led to a trip from very conservative Baptist/Presbyterian mix through Catholicism to Eastern Orthodoxy) but on a series of Bible story records my grandmother bought one a week at the grocery store. They were less an occasional read and more a constant backdrop (along with similar Star Trek, Space:1999, HG Wells, and Jules Verne records) to my life as they were used to help focus.

What is interesting is they probably let the stories soak in so they are part of my dream states in a way books do not.

I find myself saving another one of your excellent essays. You’re right, we do need to dream again!