This piece is long and your email client may choke on it. Read the original at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com.

This is a stack of books.

The reason you can only see the edges of the books, and not the legible spines, is because they are all crap.

I couldn’t make it through a single one of them. Some I quit after a page. Some I hung in for over half the length of the book before I gave up on them.

This is another stack of books:

You can see the spines on these because I actually finished them—and all of them left a mark. I still care about the characters. I still think about the arguments. They were interesting.

These two piles are sitting side-by-side on my desk, and they are the results of the last few months of reading.

No big deal, right? Anyone who’s into reading has the books that hooked them and the books that didn’t. And the question of “what makes the difference between one pile and another” is gonna vary from reader-to-reader, right?

That’s what I thought, too.

But I’ve talked to a lot of long-term bookworms in the last couple months, and I’ve noticed that our “Did Not Finish” piles all had something very strange in common:

With very rare exception, the books in the DNF piles were written in the past 20 years.

What’s more, our “finished” piles—while they were as different as we are when it comes to genre, style, and topic—featured a surprisingly large number of books written before the year 2000.

In the dozen-and-a-half people I talked to, this trend held regardless of reader age. The only thing that gave this finished-pile trend a slight buck is how plugged in the reader was to The Current Thing (the readers who are very Current-Thing minded had more new books in their “finished” pile).

What the hell is going on here?

Rounding Up the Usual Suspects

I actually first noticed this problem (and the associated pattern) back in the early 2010s, and have looked for an answer, on and off, since then. In 2014, I brought it up with a writer’s social club I was a part of.

The writers in that club—most of them older than me—didn’t think it was an interesting question. They were very commercially-minded, and believed in reading as much new stuff as possible in order to “stay current with reader tastes.” Not a stupid idea from a business perspective, but it does lead pretty much the same follow-the-blockbuster mentality that has sucked Hollywood down the creative toilet over the same time frame.1

But I was just coming out of the once-hot world of podcast fiction, where I’d been rubbing shoulders with some writers who were doing some really interesting stuff, and some of whom have gone on to have pretty damn respectable careers since.

Was I turning my nose up at what was popular because I was an indie geek?

Didn’t seem likely, since some of my favorite writers of that era were award-winning bestsellers. In fact, most good new writers I’ve found since then (including two who I fell totally in love with and who subsequently broke my heart when they revealed that they didn’t have the courage to go where their creativity was leading them) were pretty high-profile.2

So, it wasn’t chauvinism.

Could it be that I was just turning into a Grumpy Old Dan? I mean, I have been known to flirt with a modicum of curmudgeonliness from time to time, so it’s not unreasonable to think that I might just have become a stodgy old bastard who was completely set in my ways even back in my thirties.

But, considering that one of my recent informal survey participants is in her twenties and has been expressing similar gripes to me since she was sixteen years old, that didn’t seem likely either.

Could it be that I was out of touch with contemporary taste?

Well, if I was, then a number of my friends who are deeply trendy and not prone to living on a mountain in the middle of nowhere were also somehow out of touch.

What about recency bias? The writer Ted Sturgeon once declared that “90% of everything is crap,” and on that basis we should expect most new stuff most of the time to be basically worthless—that stuff from the past that we remember fondly we remember because it’s the stuff that was good enough to get passed on.

Back in 2014, this is more-or-less what I figured was going on. But something happened to me last year that turned that idea on its head.

Due to the closure of a local thrift store, I came into possession of a few thousand old paperbacks, most of them by authors I’d never read before, and a healthy chunk of them long out of print. These were not the books that survived to be passed down, reprinted, and made a part of the culture. These were the books that people donated to the thrift store.

At the same time, as a result of writing this column I’m now regularly exposed to a lot more contemporary high-profile writing (in both novels and nonfiction) than has previously been my habit. I’m getting more of the “Best” of what’s being put out today, and I’ve got a whole shed-full of the “Worst” of what was being put out twenty-to-sixty years ago. Thus, I’ve had the dubious privilege of learning the hard way that the “Best” of today can’t hold a candle to the “Worst” of decades-gone-by.

So again, I was left with “what the hell is going on?”

The Investigation Commences

This week I decided I finally had enough. After DNF’ing a dozen books in the last two months, I was about ready to hang up my bookworm spurs. If I did that, it would inevitably lead to hanging up my novelist spurs.

I had to solve this problem.

It was getting in the way of my reading, and it was getting in the way of finishing two books for my publisher (one novel, and one nonfiction volume) that are now well-overdue, partly because of this issue.

So I took my pile of DNFs (some of which are pictured above) and listed off the things I hated about them. Here’s the list:

Boring

Dull

Preachy

Lifeless

Why should I give a fuck?

I write a hell of a lot better than this jerk.

This person has no excuse for writing this poorly.

Feels like listening to news pundits.

Sounds like [redacted name of a very well-known dip shit I went to high school with].3

The writer is a coward.

The writer thinks being brave is the same thing as writing well.

I paid money for this book. Why can’t you make me care more than the cover already did?

Goddammit, tell me a fucking story already!

I know how to turn animals into meat, and writers like you are wasting valuable oxygen.

Looking for a moment beyond my obvious emotional regulation issues, there’s a pretty clear pattern in the above gripes, and as a moderately accomplished writer and justifiably opinionated reader I figure I’m entitled to get a bit nasty here:

These motherfuckers can’t write.

Why they can’t write, though, that seems to vary a lot.

Some can’t keep a thread going, and the book is a mess despite a promising topic (I will be reviewing one of these—a history book—in the not-too-distant future).

Some are trying to do philosophy when they don’t even understand their own, so their thought structure doesn’t hold up to the kind of scrutiny they explicitly invite (three very well known public intellectuals were guilty of this one). I call this the “C.S. Lewis problem,” but Lewis at least had the virtue of being a decent stylist with a vivid imagination, and a distinctive authorial voice that occasionally gave birth to something truly sublime.4

Speaking of authorial voice, most of the DNFs don’t really have one. They sound like they could be written by last year’s AI (this is award-winning stuff I’m talking about here).5 There isn’t much in the way of original thought on display. Or unique perspective. Even the biting satire book was by-the-numbers in every way, despite being written by a very sharp writer with a sterling reputation.

And this led me to start randomly plucking books off the shelf this afternoon and reading the first two paragraphs, just to see what they did to me.

Which is when I suddenly got it.

Hit Me in the Guts

Here are a few opening lines from the DNF pile:

“I was on the way to pick up a few things for dinner…”

“Johnny was twenty-two years old and only wanted to have sex.”

“I woke up early in the morning, and got up right away.”

“There wasn’t any time to lose.”

“The restaurant hummed with the noise of a busy lunch hour.”

“[Character name] wished for an end to nuclear weapons.”

Compare those with these:

“Dr Strauss says I shoud rite down what I think and remembir and evrey thing that happins to me from now on…” [Sic]

“The heavy clouds on the horizon loomed progressively lower and angrier as the road rose ever-higher into the Sierra.”

“They were hateful presences in me. Like a little old couple in the woods, all alone for each other, the son only a whim of fate.”

“The men who wanted to kill Ahmet Yilmaz were serious people.”

“I am on a mountain in my tree home that people have passed without ever knowing I am here.”

Are you seeing what I’m seeing?

No?

Look again.

Every one of that first set of openers is generic. Nothing about them gives you a flavor of what you’re in for. Nothing in them shows more than the most perfunctory character traits. Nothing in them gives you a feel for the world you’re in, or the author’s intent, or has a sense of voice. They could all have been written in an internet chat room by some rando who was too interested in the latest release of The Last of Us to give more than a passing thought to their own attitudes about the world (to say nothing of putting in the effort to get those thoughts, feelings, and attitudes across to an audience).

In that second set, though, every one of those lines says something. There’s meaning in those words, between those words, and behind those words. There’s a sense of life coursing through them, of discoveries lurking beyond them. They all tell a story (at least, an implicit one) in just that single opening line. The speaker of those lines must speak. You can feel the urgency right there in the words. And that tells you, the reader, that what you’re about to hear is worth your time.

Granted, those opening lines are all from novels, but the nonfiction in my last year’s DNF pile suffered from much the same problem—though in those cases the prose wasn’t just lifeless, it was also over-earnest. Regardless of the point of view (or lack of coherent point of view) advanced by the book, the tone and measure of the book’s writing was pedestrian, tiresome, and ordinary in the worst possible ways. In the case of the nonfiction, the authors clearly believed that what they had to say was valuable and important—important enough, even, to pour a lot of research and writing time into—but that didn’t stop them from assuming that their audience was already theirs before the book began, and consequently from taking liberties with their tone that only someone who is already a personal authority can get away with (i.e. preaching to the choir).

This is bad rhetoric, and sterile writing, and a thousand miles away from the way that good nonfiction is done (for examples of stellar 21st century nonfiction writing, see the works of Jon Ronson and Mary Roach).

The View From Nowhere

A deeper look into the DNF pile vs. the “finished” pile (and a random survey of a few dozen books on my shelves that I hadn’t read before) revealed another difference that didn’t surprise me too much, as it’s something I’ve been watching grow for many-a-year now:

A lack of intertextuality.

For those of you not on the lit-geek squad, intertextuality is the term for the links between one work and other works (especially works by other authors). These can range from direct quotations and citations of other books (as I have done in my science fiction novel The Wolf of Venus,6 which explicitly references Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson while also drawing on Brave New World, A Clockwork Orange, The Gulag Archipelago, and a few others), to clever re-castings of older tales (such as how Michael Crichton’s The Eaters of the Dead and JRR Tolkien’s The Hobbit are both essentially rewrites of Beowulf), to cribs from and allusions to Shakespeare, the Bible, Arthurian legends, The Rubaiyat, 1001 Nights, and just about anything else you care to think of.

Without exaggeration:

All good stories have an often-not-subtle intertextual layer, because all stories emerge from a cultural context. They are from somewhere, and that somewhere came from somewhere else. This place of origin gives the story a particularity, a flavor, a place to belong in the vast scheme of human experience and in the universe of thought, myth, symbol, religion, and art.

Since the end of the Cold War, the US literary class (and its hangers on in other countries) has increasingly come to believe that it has a view from nowhere. There is a presumed universalism about its experience of life, morality, development, psychology, religion, and the entire world—all while the actual worldview it holds is one of the strangest, most particularized, and idiosyncratic in the history of the planet.

This WEIRDness (WEIRD for Western Educated Industrialized Rich and Democratic), being truly and astonishingly unusual, should be fertile soil for the telling of mind-bending tales. Unfortunately, having lost any sense of its own idiosyncrasies, the WEIRD literati has also lost access to all the tools of dramatic tension (which, after all, emerges largely from the conflict between the values of different players who have reason to believe that they’re in the right) and, consequently, to the ability to find, portray, and meditate upon those human universals that truly do exist.

The aesthetic and moral cowardice that thus emerges from this blend of universalism, smugness, and ignorance of the human condition leads not just to bland prose, but to stories that have no sense of place.

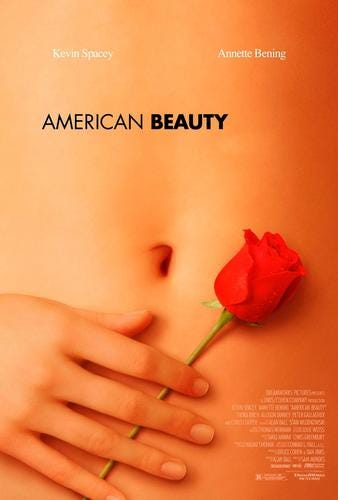

Consider the film American Beauty (I choose a film because film is more universal today than books, but a good parallel-in-book-form could be anything by John Cheever or J.G. Ballard). This twisted drama centering on the spiritual decay of upper-middle-class white suburbia starts by establishing a palpable sense of place, populating it with characters, and it does so well enough that by three minutes into the film you’re already completely locked into a strange and unusual world (despite the fact that this “strange” world is exactly the one most of the audience lives in). This storyteller’s trick of “making the familiar, strange” is essential to any gripping tale.

Yet, I’m currently reading a novel set in white upper-middle-class suburbia, and I’m shocked by the utter lack of flavor in the book. I can’t see the houses, smell the food, sense the geography, or feel the politics of the community—this despite the fact that the entire tale depends directly upon all of these things. And this is a well-blurbed and highly-praised book by an accomplished and famous novelist who’s won multiple awards and gotten the occasional film deal. The laziness of the craft is shocking (and, as you can probably tell from my tone, seriously grating to me as a novelist). The author is not doing the job promised on the book cover.

Writing Just to Write

Satirical song writer Tom Lehrer once said of the youth-rebel class of the early 1960s that “these are people who confuse ‘authenticity’ with ‘artistic merit’ and ‘illiteracy’ with ‘charm.’”

He wasn’t wrong.

But he would have been more correct to apply that diagnosis to the arts and letters scene of the early 21st century—an era that confuses “being right” with “being worth reading,” that mistakes “bare and bland” for “efficient and straightforward,” and “sexual description” for “sex appeal.”

And that’s because today’s commercial environment, and today’s culture more generally, wants things to be safe. And in today’s world—just as has happened in past periods of asymptotic prosperity and high material comfort—“safe” means “inoffensive, comfortable, reassuring, and boring.”

A few nights ago I shared The Big Lebowski (one of my favorite films) with one of my favorite people in the world.

She hated it.

It made her viscerally uncomfortable, to the point where she asked me not to insist she finish the film. She couldn’t say exactly why it bothered her so, but it did. It made her clench every muscle in her body and grit her teeth as if bracing for a bad medical experience.

I was disappointed, as I’m almost sure she’d have loved it if she’d gotten to the twisty bits at the end, but I also completely understood. The first time I saw the film I hated it too, in much the same way—I just have a high tolerance for that kind of discomfort, so I stubborned it out, and only discovered I liked it the next day when I finally got the joke and just about fell over laughing.7

Someday, her tastes might change and she might decide to try to finish the movie. Or they might not.

But whether she does or not, there is no neutral ground where The Big Lebowski is concerned. It provokes a response, even if you don’t want it to.

That’s what good art and letters are supposed to do.

With the occasional exception (like the poetry of Emily Dickinson), art isn’t merely “expressing yourself.” It’s a very specific form of dialogue and communication:

Seduction.

A book—or a song, or a film—opens with a tease, it builds tension, it explodes in orgasmic revelation and/or resolution. Good letters—whether art or argument—are polarizing. They don’t allow you to find them blase. You can love them, or you can hate them (or, most delightfully, you can hate them until they win you over by being so goddamn good at the dance).

And they do this because the rhythms of art, rhetoric, and seduction are all rooted in our bodies.

The Life of Art

Much as we might like to think so—we who live in a world with the Internet, books, ideologies, religions, and other great abstractions—we are not elevated beings able to transcend mortal concerns. We are, as Terry Bisson so hilariously pointed out, made out of meat.

Thinking meat. Feeling meat. But, nonetheless, meat.

Everything we do, everything we feel, everything we are, is done with the meat.

So what is meat?

Without getting too technical, meat is a feedback-regulated biochemical substance seeking homeostasis through the proper balance of inputs and excretions through a process that we call “metabolism.”

And in order to seek homeostasis (and the experience of stability and health thereby achieved), our meat experiences the world, and responds to parts of the world finds interesting with hungers. Those hungers create pressure inside of us, which pushes us to act in the direction of the hunger—and we’ll keep acting in that direction as long as we continue to receive promising signals, even if we are also receiving unpromising signals at the same time.

We do this because the more difficult the hunger is to satisfy, the more satisfying and pleasurable the experience of fulfilling it.

Slot machines, video games, social media, and fast food advertisements all stimulate hungers and satisfy them unreliably and incompletely in order to keep us hungry even when we’re freshly sated.

Relationships, good art, good food, sex, exercise, and good drugs (i.e. pleasure chemicals used in a healthy manner) all stimulate hunger and fulfill it in a way that fully satisfies, until our meat goes once again out of homeostasis.

This is why religious initiations exist. It’s why way-points on the way to any career goal exist.

And it’s why rhetoric and literature are all—and always—structured as seduction.

It starts with an advertisement: Here’s something to whet your appetite and get you invested enough to keep going.

It continues with a build: Here are things that don’t paint a full picture yet, but aren’t they enticing? Don’t you want to know how they fit together?

It entangles us in complication: But now something’s changed. Things don’t look like they thought you were going to—how is it all going to end?

It climaxes with revelation: THIS is what you’ve been waiting for. THIS is what you want. Doesn’t it feel good?

It concludes with reflection: Aren’t you glad you stuck through to the end? Now you can tell your friends what you thought. Even if you hated it, at least you danced the whole dance. Now you have something new in your life to talk about.

Remove that dance (from any part of life), and you have…nothing.

No meaning. No joy. No anger.

Just flat, dull, gray nothingness.

A cubicle farm filled with meaningless TPS reports. A blank page in your mind. A context free Severed existence.

You can have ideas, mathematics, facts, and inputs galore. You can have the solution to every problem in the universe.

But humans don’t want solutions.

They want to solve.

They want this because it is the process our bodies are built around. It’s why the end of a mystery, or a good debate, or a great song, changes your pulse, your breathing, your skin conductance, your sweating, the dilation of your pupils, and sometimes the tumescence of your erectile tissues:

Imagination, intellect, and meaning aren’t political, philosophical, or theological.

They are gustatory and sexual.

They are made in the meat.

A society which hates or dismisses the body, that values the virtual and conceptual to the exclusion of the embodied and the physical (rather than in addition to them) can’t help but produce art and letters that are trivial, dull, and forgettable even when the ideas expressed in those works are profound, earth-shaking, or razor-sharp.

The old books are better—not because the older artists were smarter, but because they understood that, with every sentence, they had to secure your buy-in.

They had to meet you in your meat, and they were willing to go to great lengths to do so. Their readers were worth getting dirty for.

In other words, they treated their readers like they mattered.

They never took their audiences for granted.

This column is a big part of how I make my living—bigger now due to recent exciting events which you can read about here. Because of this, I am currently seeking consulting, coaching, and production gigs.

I am also offering a 20% lifetime discount off the annual subscription rate. If you’re finding these articles valuable, I’d be honored to have you join the ranks of my supporters!

If you’re looking for tales to transfix your imagination, you can find my novels, short stories, visions, and dreams (along with some how-to books and literary studies) by clicking here.

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. If you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

It’s worth noting that reader “demand,” as such, is not entirely organic. As with movies, packaged foods, pop music, or anything else like that, the bulk of what makes a hit with the “mainstream” is that for which the demand has been created by clever marketing. That’s why surprise break-out hits tend to re-form the industry around them. Examples of such surprise break-outs in the publishing industry include The Hobbit, Harry Potter, and The Hunt for Red October.

I mean, really, it is difficult to NOT run into high profile books if you prefer the brick-and-mortar bookstore experience to the online bookstore experience.

This is a surprisingly common problem with regards to this particular dip shit.

I discuss one of his three best books in this article:

I say this in full knowledge of the irony on display: my books are art of the stolen dataset used to train the current crop of LLMs, so there’s a chance that I will soon be accused of “sounding like AI.”

You can find The Wolf of Venus in its serialized form by clicking here.

You can read my breakdown of The Big Lebowski, which will give you an idea of why people find it so polarizing, in this article:

In Defense of Arrogance and Heroism

Note: the following article is a rant. The carefully-chosen words and balanced approach you’ve come to expect from this author are not in evidence. Profane language is front-and-center, and provocation is intended. You have been warned.

Oh, excellent. I've been thinking something was wrong with ME because my DNF pile keeps getting bigger and bigger and I rarely finish a new book these days...just re-read the old ones. You are so right.

> Dr Strauss says I shoud rite down what I think and remembir and evrey thing that happins to me from now on

This is uncanny. Just yesterday my daughter was going through a "must-read" book list and asked me about Flowers for Algernon. My aswer was a more polite rendition of "hell, yes!!"