Let’s face it, Gen Xers and Millenials have been shitting a lot on the Boomers the last few years. I’ve done a fair amount of it myself. However, the disasters that have followed in the wake of their insane population bulge (as well as the ones yet-to-come) may wind up being survivable because of something astonishing that the Boomers—and especially the subset known colloquially as the “Hippies”—did.

So buckle up for a tale about how bored kids looking for a place in the world literally saved the heritage of the Western world.

By the way, this post is long with many images. Your email client may choke on it. If it does, read the original at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com

By a strange series of events involving a mis-scheduled photo shoot with a model, I found myself at an event in a small bohemian town in California. There, surrounded by strangers who felt immediately like family (and who did, in fact, become family over the following few years), I learned the lost art of Medieval English ceramics.

When it comes to the history of ceramics, the Chinese have always gotten the loudest attention. Their invention of Bone China, with its lightness and near translucence, combined with their mastery of glazing technology hundreds of years ahead of that of their European rivals, is enough to justify the obsessive interest in their art among ceramicists, archaeologists, historians, potters, and collectors.

But the fascination with Chinese pottery, which really got going among the Victorians, was one of several reasons that English ceramics (judged not-very-impressive by comparison) got far less attention than it deserved.

Ceramics are one of the earliest, and most important, technologies of human civilization. The ubiquity of pottery makes it the foundation of archaeological chronology at most sites. The design and decorations of the shards, and their precise chemical makeup, allow archaeologists to date a given layer of a given site quite precisely—often to within a generation or two for civilizations where a lot of data has already been unearthed and systematized.

So, pottery is ancient. You take some mud, you throw it in the fire, you get something ceramic. Someone was bound to figure it out sooner or later, right?

Well…not really. Hardening a clay pot by throwing it on the coals is as far away from ancient pottery as hardening a wooden spear point over the fire is from smelting copper and tin to make a bronze spear point.

This is a surprisingly advanced technology.

Pottery happens because clay of a certain consistency of grain and chemical content vitrifies (that is, turns into glass) in a narrow temperature window over a specific period of time. And, if you’ll recall comments I made in my most recent maker post, when you put heat into something, it expands. Silica (and the things made from it, like glass, pottery, and microchips) does this the same way that metal does.

The rate of heating, and the rate of cooling, and the oxygen content of the atmosphere in which pottery is fired affects both the characteristics of the body of the pot, and its surface finish. Thus, in a world without valves, electronic controls, thermometers, themocouples, and oxygen sensors, a skilled kilnsman would have had to somehow properly control all three things.

And we’re supposed to believe that all this magic with chemistry, fire, and materials science was pulled off by ancient people who were too stupid to make toilet paper?

Shit man, that’s enough to make anyone think…

Okay, not really, but it’s worth remembering that chain of reasoning next time you see someone invoking a great unknown enlightening force (whether aliens or gods) to cover a gap in their own imagination.

Ancient people were really clever—far cleverer than we are.1

Anyway, like I said, Chinese ceramics have been studied extensively by the Victorians, and their traditional firing practices and clay recipes were well documented (as you would expect, given both the Victorian mania for all things Oriental2 and the fact that the Chinese wrote everything down).

The medieval Europeans, being largely illiterate, did not leave these kinds of records. The reason this period is sometimes called “The Dark Ages” isn’t because it was a “Dark time in the history of humanity” (the current picture of medieval life that emerges from historical studies is quite pleasant, vibrant, and literally colorful—at least when there wasn’t a plague, war, or famine afoot),3 but because they left very little in the way of records, and therefore there is very little “light” for historians to navigate by as they try to reconstruct the era.

Which brings me back to that bohemian enclave in California, where a pair of Ph.D. archaeology students were trying to solve the puzzle of how the medieval English pulled off their own pottery mastery.

How did the medieval English fire their pottery?

Of the several sorts of kiln remains that have been unearthed from the middle ages, the most common sort is (or was) also the most mysterious: the small-scale updraft kiln.

Consider a campfire, or a fireplace. Chances are you’ve played around with one or the other, so you know from experience that you can get a fire of a few hundred degrees by piling some wood together and setting it alight. You can use it to cook food or keep you warm in the winter.

But pottery requires a lot more heat than either of these typically puts out. To get more heat out of a fire, you have to inject more oxygen. Blacksmiths used to do this with bellows4—pump the bellows, force a jet of air into the coals, and you can push a fire from red-hot to white-hot, allowing you to heat your steel to north of 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (which is hot enough that it’s almost melting—this is the temperature at which solid-phase welding occurs).

These common little updraft kilns never showed up with evidence of a bellows, or even a bellows hookup. So how the hell were medieval English potters making their fires hot enough to fire pottery? And how hot could they get, anyway? Could they get hot enough to manage terra cotta, or could they do ceramic tiles? Could their heat and oxygen level be managed well enough to do glazes using only the tools we know they had?5

This was what those two archaeology students were trying to figure out. The one of them who went on to get his Ph.D. depended upon the research he conducted in this backyard updraft kiln to write his dissertation.6

What Is Civilization?

I’m about to make the argument that, perhaps by accident, the hippies—that subsection of the Boomer generation that caused all the noise in the 1960s with their rootless wanderings and prolific cultural experimentation—saved Western civilization, but to do so would beg the question regarding what I mean by “civilization.”

The root word of “civilization,” after all, is “civitas,” which roughly translates to “city” in Latin. “Civilized” behavior (more-or-less) is that behavior which hews to the kind of manners it takes to get along in a city, where you’re surrounded by strangers and nobody really knows you. When you’re with people who know you, you can flick boogers, make taboo jokes, talk in funny voices, show your ass in response to a rude comment (literally), and nobody cares. They’re your friends/family, they know you, they know what these weird behaviors mean when they come from you.

When you’re with strangers, you’re never going to express your uncensored self, because you want the strangers around you to take you for a trustworthy and non-dangerous person (generally). Therefore you tailor your presentation of self to something that they will understand as being more-or-less what you wish to project (whether this projection is intended to convey the gestalt of your authentic self or not).

My homesteading partner and I are currently seeking gigs for editorial, layout/design, voice over, audiobook narration, and strategic consulting work. Additionally, if you’re looking for a tutor for a student struggling with history, English, creative writing, or psychology, I’m available for hire.

Or you can help out substantially by joining me here as a paid subscriber.

But “civilization” is also used to mean “cultural legacy.” When you invoke “Western Civilization” or “English Civilization” or “Arab Civilization” or “Chinese Civilization” you’re not talking about a city, or a city-state, or even a state entity at all—you’re talking about a complex tradition involving myths, ethnicities, arts, crafts, norms, moral codes, and the worldviews that arise from the interactions of all these things.

Excepting human biology, all civilization is under-girded by two—and only two—basic factors (and you have no idea how it pains me, as an artist, to say this):

Geography and technology.7

Geography and all its features (climate, soil, minerals, landscape, water, available flora, available fauna, other people-groups, astronomy) sets the survival environment for a people-group. Technology allows that people-group to change what the significance of those environmental factors. The interaction of people with their environment creates their culture,8 and the technology those people use changes what that environment means, and also how people see themselves in relation to their environment, and to each other.9

But technology changes.

It changes all the time.

And even in the pre-industrial before-time, it changed at a fairly rapid clip, because humans are wily bastards who are always looking for new tricks that might help them eek out a new bit of advantage here and there.

Technology is also known as material culture for this reason. Advances in technologies transform social realities and open up new avenues for the development of novel social technologies (including both reforms experienced as positive by most people, and methods/protocols/hacks/exploits/corruption angles that provide a new battleground for the capture of political power, whether legitimate or illegitimate).10

And, most importantly, technology at root is not “gadgets.” The gadgets are the products of technology, not technology itself. Technology, as Jacques Ellul spotted, is “technique.” The understanding of how things are done. One of the difficulties of any given technological domain is that it has its own internal logic, and the obvious benefits of that technology are so profound that they easily sweep human concerns away when humans aren’t really paying attention.11

Technology is culture and civilization, because technology is, at heart, knowledge rather than artifact.

Because of this, it has a terrifying vulnerability: Just like with artistic culture, religious culture, and political culture, all material culture is always two generations (or less) from extinction.

Technological Delicacy

In a stone-age context, the extinction of a trade in a region wasn’t necessarily a terminal long-term blow, because the secrets of that trade could eventually be re-discovered (or, at worst, “borrowed” from a neighboring nation).

In a post-Industrial context, on the other hand, the technology is substantially advanced and protected in such a way that re-creating it when it’s lost is not easy.12

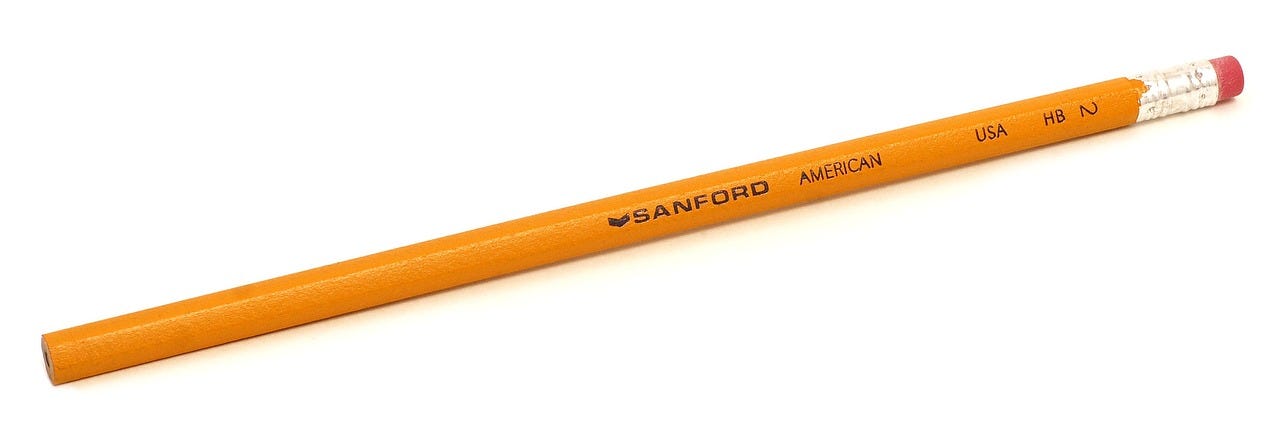

Back in the 1958, Leonard E. Read wrote an essay called I, Pencil, which details all the myriad steps involved in the manufacture of a simple pencil. From the graphite to the wood to the metal band to the rubber to that stupid yellow paint, each piece of the pencil has an astonishing chain of technological craft behind it, and the creation of each piece in turn depends on machinery which, itself, has a similar technological knowledge and supply chain behind it. Once all the parts are accumulated, they must be assembled, packaged, and shipped out—work which, again, depends on an impressive array of machines and protocols that each have their own similar story.

All of this goes into the manufacture of the humble pencil depended upon by billions of schoolchildren to fill out the standardized tests which formally legitimize the salaries their teachers depend upon to pay rent.

You can read this tale for yourself at the Foundation for Economic Education, and it’s really 101-level stuff if you’ve done any study of basic economics.

Now consider the article you’re reading right now. Going by the numbers, you’re reading this on a cell phone. If you’re not, you’re on a computer or a tablet—their stories are similar, but for brevity’s sake, let’s just consider the cell phone. That little device in your hand has thousands of supply chain steps across more than a dozen countries. From the raw materials, to the transistors, to the chips, to the lenses, to the capacitors and batteries and displays and antennae, to all the raw materials they’re all made from. Each one of those manufactured bits is made in a factory, on specialized equipment, producing fantastic economies of scale.

In most ways, it’s the same story as the pencil, but there is a key difference:

If you needed to, you could make a pencil. Sure, you might have to use charcoal instead of graphite, but if you needed something to do what a pencil does, and you had no way in hell to buy one, you could make one.

But there is nobody on Earth who knows how to make a cell phone.

Well, that’s not exactly true. It’s more accurate to say that no one person or organization knows how to make an entire cell phone. If the rest of the world suddenly disappeared and the US was all that existed, there is enough of the culture part of our material culture13 in this country that we could have new phones again after about ten or fifteen years of rapid build-out of chip fab, mining operations, and other facets of that supply chain, but each of those steps would still be highly specialized and, if you wanted something more sophisticated than just the ability to use the phone, the technological expertise would still be spread across a number of different localities.

But Dan! I hear you cry, How is it possible that nobody knows how to make one of these things? Doesn’t Apple or Samsung or Motorola have assembly manuals, spec sheets, chip diagrams, and all that good stuff?

Well…no, actually, they don’t. They have those things for those items which they produce or design in house. For everything else, they’re doing what any yahoo with a home electronics bench would: buying off-the-shelf parts.

Those parts are, in turn, designed, fabricated, and sold by other companies, using their own proprietary processes and supply chains.

The world is made of Legos, which is great…except and unless something important goes tits-up.

This is from whence the doomsday crowd draws their basic intuition. If there’s a nuclear war, or a moderate-sized asteroid strike, or an economic collapse that drags the system down beyond a certain point, this entire delicate web of interdependence goes poof. When you consider that the easy coal has all been mined already, that the oil that you can find to without computer imaging has mostly been pumped, it’s pretty easy to draw the conclusion that “If this system goes down, we’re doomed forever.”

But that’s not necessarily the case anymore…thanks to the hippies.

From Folk Music to Folk Wisdom

If you, stuck as you are in the 21st century doldrums, were to spend any time reading up on, or watching documentaries about, the 1960s, you might be struck by how…weird everything was.

I’m not talking about the drugs, or the music, or the politics, or any of that stuff. Those are all secondary effects of something way deeper that was going on:

The largest generation (by percentage of population) in the history of the world was coming of age, and it had no idea what to do with itself. The economy hadn’t grown enough yet to absorb them. Everything they’d been taught about how politics, history, morality, and economics were supposed to work in the United States was something between a fable and a lie.14 Many of them were understandably pissed, many more of them were willing to go along anyway because the lies were noble, but most of them were, at least for a time, lost.

The drugs, the cults, the free love, the communes, the hitch-hiking, the music, the art scene—their ubiquity and potency were all a secondary result of the biggest generation in history trying to find their bearings.15 You can hear it in the music—for example in this plaintive lament by Paul Simon about a forlorn couple traveling the country trying to understand what America is really about.

Five years after that song was released, Peter Jenkins (another Boomer hippie) actually did what the song talks about: he walked across the nation to try to figure out what America was about and whether he wanted to belong here. His memoir of the journey was published in two volumes: A Walk Across America and The Walk West. Both are essential reading.

But back to Simon & Garfunkel and their song…

This ditty is an example of a short-lived 1960s and 1970s genre called “folk rock.” Musicians in this genre felt as lost and rootless as their fellows, and they solved the problem by walking across America, musically. They went to tent revival meetings in the south, they traveled to the hollars in Appalachia, they hung out in blues bars in South Chicago and the deep Louisiana delta. They produced glorious songs like Ode to Billie Joe, incredible albums like Taproot Manuscript, and unparalleled and unexpected symphonies like A Love Supreme. Bob Denver, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Neil Diamond, Paul Simon, Leonard Cohen, Kris Kristofferson, Bobbie Gentry, Bob Dylan, (and dozens of other songwriters of the era whose music was covered far and wide) dabbled in and/or led this movement.

And, across the water in Britain, the same thing was happening with traditional Welsh, Cornish, Celtic, and English music, which made its way into fusion in everything from Jethro Tull’s Bungle in the Jungle to Led Zepplin’s Stairway to Heaven.16

This embrace of folk music traditions had a political element, too, as at the time to be “Left Wing” was to be interested in the little guy, in worker’s rights, and in resisting the Post-WW2 fascist17 imperial system that had regimented and restricted life like never happened before in either the UK or the USA, especially in peacetime.

But the hippies didn’t just do this with music.

Along with an interest in folk music came an interest in folk craft. Woodworking, blacksmithing, bladesmithing, gunsmithing, organic agriculture, pre-tractor logging, fiber arts (weaving, knitting, spinning, crochet, macrame), sculpture, stonemasonry, ancient construction techniques (such as timber framing), tool-making, bushcraft, pottery and ceramics, chemistry, herbalism, bookbinding, paper making, hunting, leatherworking, and on, and on, and on.

You, of course, know about these things from YouTube, reality TV shows, and all sorts of other media. These things only exist because these rootless wanderers decided to walk off and look for America.

Because what they often found when they went looking for the pre-industrial root crafts, and especially for people who could teach them these ancient ways, was that there was almost nothing left.

Bill Morgan, for example, was on a mission to learn the ways of American bladesmithing and discovered that there were only around a dozen people left in the United States who knew how to forge a knife in the traditional fashion. He founded the American Bladesmithing Society to rescue that knowledge and resurrect the craft. Similar movements happened in blacksmithing, pottery, folk medicine, and a number of other fields.

Where formal societies weren’t formed, informal interest and hobby groups arose. New books were produced that documented older practices, and old books—long out of print18—were located and brought back into print with new introductions and commentaries (in some cases, the English was archaic enough that these commentaries amounted to a gloss-style translation).

The discipline of experimental archaeology—once a small corner of the archaeological world—also got a fresh influx of enthusiastic students. These students (and their students), have, in the past 60 years, managed to resurrect, re-create, and experimentally reproduce dozens upon dozens of lost artifacts and crafts, including those that are now being used to re-construct Notre Dame in Paris.

For the first time in human history, you—yes YOU—now have the ability to get a book, or a video course, or find a personal tutor on any craft in human history for which there is surviving evidence.

Want to make papyrus or silk? Want to build a rocket and synthesize the fuel in your back yard? Want to smelt steel from the sand in the river bed? Want to build a lathe using sticks that were cut using axes made from stone? Want to learn any of the martial arts that were ever written down? Want to make armor, or chandeliers, or tables? Want to make arrowheads and hunt according to the Chippewa tradition? Want to make all the tools you need to make these things, and to do it from raw or salvaged materials without ever touching virgin stuff from the supply chain?

There’s a book, or podcast, or course, or video series for that.

But more important, there’s a society of people out there who do that thing, and they’ll show you how (usually for free) because they love it. And they’ll love you just for being interested in it.

Save the Civilization, Save the Human Race

Our technological civilization is fragile, and its chief vulnerabilities come from two angles:

The robustness of the supply chain and the knowledge contained therein, and

The distance between what we can do with our hands and what our automated systems can do

The first one of these we’ve all become suddenly and practically acquainted with over the past few years (assuming it wasn’t already an area of interest). And we’re gonna keep getting re-acquainted with it over the next eight-to-ten years as it keeps turning up like the neighborhood drunk stumbling into a family restaurant and puking all over the salad bar. We live in interesting times.

But the second of these?

That’s where the story gets more interesting.

In 1960, the gap between the products of our complex material culture (and what they could do) and what could be done if the system crashed was far broader than it is now. Back then, everyone was looking to the future, to automation, to complete freedom from physical labor. The old ways were quaint, tiresome, injuresome, tedious, and low class. So all the people who knew those ways were dying out, and they were taking that knowledge with them, and good riddance to all that old trash.

With the exception of pharmaceuticals, all of the staggering rapid technological advances that make up the substantive differences between your world and the world of the World War 2 generation has happened in two, and only two, areas:

Materials science

and

Transistors19

In materials science, it took four generations to go from Bakelite to fiberglass, epoxy, and carbon fiber. The chemical cracking processes for making the plastics necessary to sustain a technological, space faring civilization are both well out of patent and easy to build from scratch using basic machine tools.20

It only took three generations to go from vacuum tubes to cell phones and the Internet. The theoretical advance from vacuum tubes to transistors happened in just thirteen years.21 The essential nature of that breakthrough is conceptual—the materials science part of it is fairly trivial (though raw materials are a bit more difficult).

If it all collapsed tomorrow, we’d still stand a pretty good chance of crawling back up to the Industrial Revolution within a generation or two. By reviving the ancient crafts and material culture, the gap between “what can easily be done without the industrial revolution” and today’s world has narrowed. The floor to which we could theoretically fall has been raised.

And because those hobby-societies and professional societies have—at least in every one that I’ve looked at or participated in—continued to innovate and advance and integrate knowledge discovered with advanced scientific instruments and tools, while remaining within their ancestral paradigm, that floor is higher than it was before the industrial and electronics revolutions transpired. Thus, our civilization and culture is now much more likely to survive and rebound after a catastrophic collapse.

All of which has a fairly staggering consequence:

Our species is more likely to survive long enough to reach out into space in a permanent way. In the long run, this is the only way we will ever be able to ensure our progeny’s survival in the event of a meteor strike, or a rogue planet, or the death of the sun.

That very long term future—the one in which we spread life throughout the galaxy—is now more likely than it was when the Boomers were coming of age, thanks to their rootlessness and boredom.

So we can hit reset on that one. We are now, once again, two generations from technological extinction. So I urge you, if you haven’t already, to find an obsession, make it a hobby, and pick up the baton.

The torch of human civilization is being passed once again. Are you going to pick it up and carry it forward? Or will it die on your watch?

This isn’t because they were necessarily smarter, but because they spent their whole life problem solving so they got a lot of practice with experimentation, lateral thinking, and the other practical aspects of creativity.

A word meaning, literally, “From the east.” The opposite is “Occidental,” meaning, literally, “From the west."

A good place to start learning some of the ins and outs of medieval life is on the YouTube channel Modern History TV, which is quite good on the middle ages period.

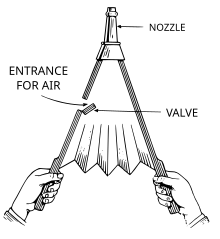

In case you’ve not run into these gadgets before, a bellows is a pair of boards connected by leather. The boards are hinges at one end while the other ends move apart from each other. There is a check-valve in one of the boards, which draws air in as the boards are pulled apart, but is kept closed by air pressure as the boards are pushed back together. Near the hinged end, a nozzle sprays a high-pressure jet of air as the boards are pushed together.

Since I never answer these questions in the body text, here’s what that experimental archaeology group discovered:

The updraft kiln, because of its design, pumps its own air at an incredible rate, enough to achieve temperatures sufficient to make glazed pottery and ceramic tile and—if skillfully managed with the right fuel feedstock—any type of pottery up to (but not including) porcelain. It’s much more labor intensive than the methods developed later on that have better documentation, and would have required community events to sustain the fires in the small villages of the middle ages. Nonetheless, the flexibility and control-ability of the kilns was sufficient to accomplish anything a medieval ceramicist might need, and could do almost everything for a modern ceramicist as well, in a pinch.

Dr. David Strange-Walker, a.k.a. Dr. David Walker. The dissertation is entitled “Understanding Pottery Kilns.” It’s an unusually good read for an academic paper. Alas, I have been unable to find a copy online to link to.

Please note, I’m not saying Geography determines a culture and all its features. Instead, like our genetics, it sets a range of possibilities. The culture develops in dialogue with it.

For example: Cultures based around irrigation tend to develop bureaucratic and authoritarian forms of government quite readily. Cultures based around being a trading port tend to develop mystery cults and high culture and republics quite readily. Cultures based in arid environments tend to develop dualistic theologies quite readily. These are trends rather than fate—there are exceptions to most of the above, but, absent other counter-veiling forces, the environment tends to push such cultures in these sorts of directions.

I talk about how this works in the essay The Metaphors We’re Made Of.

This basic fact of human society serves as the conceit upon which the entire genre of Science Fiction is built.

Jacques Ellul’s book The Technological Society is a bracing inquiry into the sociodynamics of the development of technique. While it was a serious influence on Unabomber Ted Kaczynski’s Industrial Society and its Future, Ellul’s approach is both more nuanced and more realistic (and less destructive) than Kaczynski’s, especially when it comes to mitigating the downsides of the momentum of the logic of technology.

And, of course, between these two points there is a broad gradient.

i.e. the industrial know-how, the engineering expertise, the hands-on experience, etc.

If you think the audacity of the propaganda we’re subjected to now is astonishing, imagine that your only at-the-ready access to information came over state-controlled media and through schools that were actively attempting to build a new national mythos in the aftermath of a world war. Imagine it was as bad as it is now, but you never had any clue—or any chance to find a clue—that you hadn’t been told the absolute truth until you got into college and started reading old books, formal research, and the propaganda spread by the nation’s discontents (often funded by its major geopolitical rival).

I daresay if you were to rewrite that sentence substituting “internet usage, video gaming, social media, performative sexuality, and too much porn” you’d have a pretty decent description of what’s going on at the moment, for similar reasons.

The movement was longer-lived in the UK, I suspect due to the physical proximity of the songwriters and the cultural roots upon which they were drawing.

I’m using the term literally, not as invective. The Post-WW2 American and British systems featured a wholesale integration of Government with Big Business on all matters, from market control to product design to international coups and geopolitical gamesmanship. This fact was considered entirely banal by the establishment after World War Two, to the point where, in 1953, GM President Charles E. Wilson once explained his political and managerial philosophy to a congressional committee that “…what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. The difference did not exist.” (He was under investigation for potential conflict of interest regarding his political positions and his chairmanship of GM).

The quote has entered the popular consciousness as “What’s good for GM is good for America,” which is both more brazen and a step farther than what Wilson would have been comfortable with, but such quotes morph into their legendary form because that legendary form captures a truth in the public’s understanding of the world that isn’t otherwise easily summarized.

For an example of this dynamic in action, look to the case of the United Fruit Company and the coups undertaken by the CIA on its behalf.

One classic that springs readily to mind because I’m looking at my copy on the shelf right now is Ten Acres Enough by Edmund Morris, a nineteenth-century homesteading guide that was resurrected from extinction by hippies involved in the Back-to-the-Land movement of the early 1970s.

Literally all other new technologies you can think of—from workable jet engines to 3D printing to reusable rocketships to microwave ovens—are downstream from these two.

A similar story can be told for the advances in ceramics, metallurgy, foam, and other branches of materials science.

Manufacturing technology had to catch up, but transistors were replacing vacuum tubes on the consumer market by the 1950s, which is about a generation-and-a-half after vacuum tubes were introduced.

This post was a feast! Thank you.

"So we can hit reset on that one. We are now, once again, two generations from technological extinction"

Can you explain this a bit more? What specifically is causing that timeliness of two generations? Is it another cycle of "old ways dying out"?