This piece is long and filled with pictures. Your email client may choke on it. Read the original at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com.

I got my first (small) bulk order as a blacksmith a couple weeks ago. An enterprising local couple thought my steel hair pins would be an excellent addition to their RenFaire leathercrafting booth.

Now, as you might have picked up from my recent series of posts (read the series here in order: #1, #2, #3, #4), I spent far too much of the spring off-site, and consequently was not able to keep up my forging practice. Like any other hard skill (meaning, one that requires feedback from the real world), forging well doesn’t just take mastering theory, it requires an immense amount of repetition. The art of the hammer is as subtle and demanding as a magician’s sleight-of-hand or a guitar hero’s sleight-of-fingers.

I was out of practice, but I also had an obstacle:

My forge is kaput.

You’ll remember how, late last year, I did a lot of welding in my forge for that chainsaw damascus project?

When you use heat to join together pieces of metal (an ancient process called forge welding or fusion welding), you generally add a second ingredient to your metals mix: flux.

Flux is a mineral agent that helps dissolve oxides and prevent new oxides from forming. You can use salt, or sand, but most people use borax.

Borax—sodium borate—has a pH north of 9, which is pretty damn caustic. This caustic property means that, when you melt it, it forms a lava-like goo that coats and eats anything it touches. So, it coats weld surfaces to keep oxygen out, and it eats forge scale like candy.

This is weird flaky gray stuff is forge scale:

It’s a form of iron oxide that isn’t rust—it forms when hot iron comes into contact with an oxygen-rich environment (such as the air we breathe). You generate a lot of it when you’re forging, which is why flux helps with welding.

Alas, one of the huge downsides of a propane forge is that it’s lined with refactory concrete, fire bricks, and high-temperature insulation—things that liquid borax eats even more efficiently than it eats forge scale.

So when I started working on the pins, I found that some spots on the outside of my forge were heating up to white-hot. A look inside (after it cooled) revealed a Venusian hellscape.

You’re looking at the (removed) lining of my forge. The rocky stuff is fire brick and refactory concrete. The weird glassy stuff is firebrick and refactory that was eaten by borax and then solidified into a glass puddle when the forge cooled off (and re-liquifies when heated up). The white stuff is the mineral wool insulation (basically a cancer-free not-quite-asbestos sock) that stuck to the refactory when I chipped it out.

If you think that’s ugly, it’s not half as ugly as this:

That is what the mineral wool looks like now. Where once it was a plush white layer an inch and a half thick, it’s now torn up to rags. Anything in there that’s not white is a place where the borax ate all the way to the frame, leaving a channel for the heat to shoot through and turn the forge structure into hot smithing-ready metal (and oxidizing it, and eroding it, as a consequence).

I had hoped I would be able to just add more refactory cement to the insulation. I have a bunch of it on hand, and it’s a quick job. But one look at that insulation revealed to me the tragic hubris of my ambition. That forge needs a full re-line, and that costs money.

And, as I mentioned in the following post earlier this week, money is pretty is tight right now.

That meant that I was going to have to face my own personal monster—the solid fuel forge.

The Ways of the Ancients

Most professional smiths use propane nowadays because it’s easy, the fuel is relatively cheap, and it’s a very low-mess process. It’s convenient, and the only thing more convenient (for people who live on-grid, anyway), is an electrical induction forge.

But, to be completely honest and fair…

Propane is for poseurs.

It’s so easy it allows you to turn out decent products without ever having to learn much about metallurgy.

But before about fifteen or twenty years ago, propane forges were a rich man’s toy: Difficult to build, expensive to buy, and tricky to use well. For all of human history before that time, if you wanted to forge, cast, fire, melt, smelt, or glaze1 something on a less-than-industrial scale, you didn’t burn gas to do it.

You burned something solid: wood, coal, charcoal, or peat.

Hell, some solid fuel forges burned corn:

If you can set it on fire, and you can blow enough air into it, you can get it hot enough to melt steel.

A solid fuel forge is basically a little pit (a few inches deep) with a blower hooked up to it. You build the fire in the pit, blow air into it, and Bob’s your uncle.

Assuming you designed the air channel correctly.

And that your blower pushes enough air.

And, if you’ve got all that down, you still have to learn to use the bloody thing. The fire in a solid-fuel forge has different zones with different chemical properties, which allow you to reach different temperatures, and makes your metal behave differently.

Before twenty years ago, any blacksmith knew this stuff in the same way you know how far to turn the steering wheel in order to change lanes on the freeway. But when you learn to smith in a propane forge, moving to solid fuel is like getting into a stick shift car after years of driving an automatic:

You gotta to learn all over again.

And that’s if you don’t have the problem I had:

My blower was broken.

It Really Blows

I would totally not win an authentic old-timey homesteading merit badge—not only did I cheat by learning to smith in a propane forge, I also cheated by buying a blower for my solid fuel forge.

The ancients, of course, did not have blowers. They, instead, used bellows.

You’ve seen these in cartoons, and you might have used one if you have stayed in a home heated with an old-fashioned wood stove (i.e. one without a blower built into it). The expanding chamber is made of leather, and it has two one-way valves built into it. As you draw the handles apart, it inflates through a hole in one of the panels. As you squeeze them together, the air gets pushed out the nozzle.

This is how everyone—potters, smiths, casters, glaziers, smelters, alchemists—blew air onto fire before a couple hundred years ago.

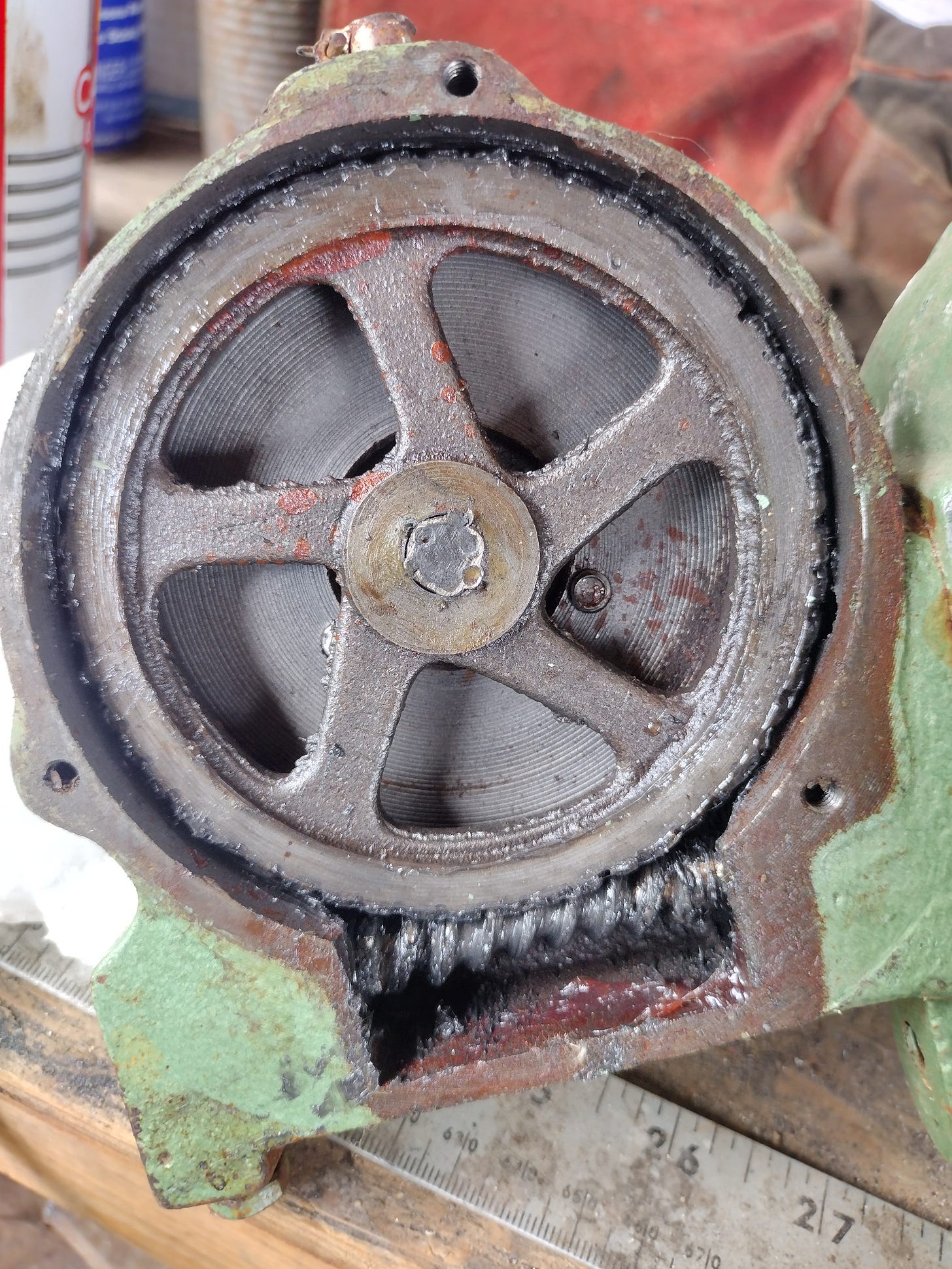

This is a blower:

This one was made in the 19th century and is still in service today. It’s actually for sale at the time of this writing (for a price I can only dream of affording). The inside of that blower looks pretty much like the blowers in your car or your HVAC system. It contains a paddle-wheel style fan which focuses the column of air it pushes.

Turn the crank, the fan blade turns, you got air. It’s basically a hand-powered hair dryer, but you can control the speed on it (air pressure control is important when smithing).

Unfortunately, I haven’t yet been able to afford one of those beautiful antique blowers. I had to settle for the Amazon special made of 100% cheap Chinesium.

Now, credit where it’s due, this thing moves a lot of air, and it’s perfectly adequate for the job, so long as, for example, the gearbox cover plate doesn’t shatter when you bump into it.

Like this:

You can tell from the JB Weld and cardboard that I made a very unsuccessful attempt to bush fix the thing when it first broke last year. Alas, it turns out that the plastic it’s made of doesn’t work happily with epoxy, and the fix lasted all of a day before it broke again.

This piece doesn’t just hold the gearbox in and protect it from dust. That bolt in the middle holds the gears in alignment.

If those gears don’t line up exactly, they either fail to engage, or they grind. This means that the plate itself is always under a bit of tension, as that bolt holds the center spindle down, which keeps the round gear from coming out of alignment with the worm gear.

The rest of the blower body is cast iron. The cover plate is (predictably) made of unreinforced ABS plastic (which is some of the most fragile and brittle stuff you can work with), and that’s why this blower cost me $30—I bought it back when inflation was still doing flowers-and-chocolates with the value of the dollar, back before it had moved on in its seduction to lube-free buggery.

Forced to choose between re-lining the propane forge and fixing the blower, I faced the music.

I pulled the cover plate (which looked even worse on the inside)…

And set about making a replacement part.

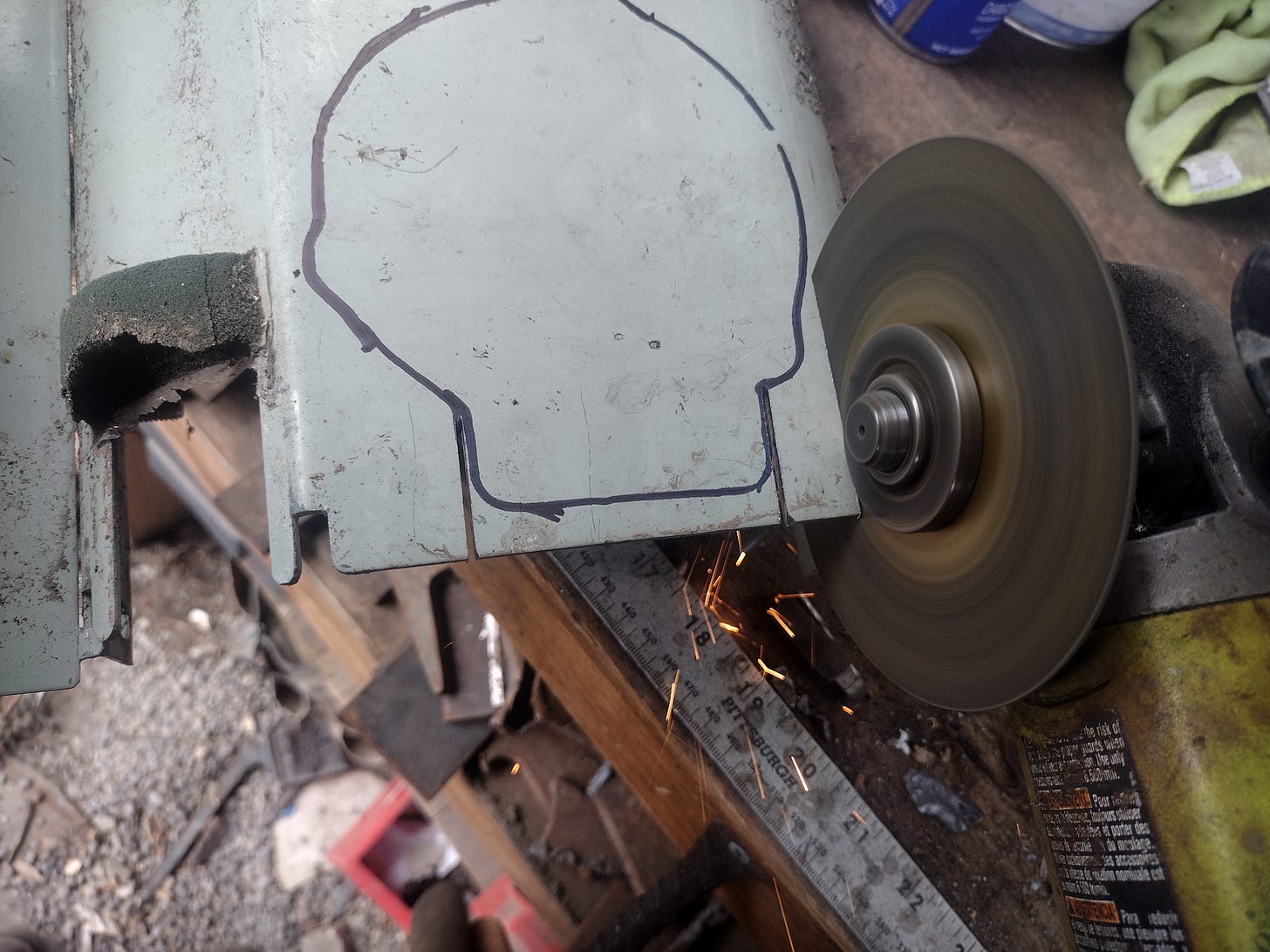

A trip to the scrap pile netted me part of an old utility box that had been destroyed in a car accident…

I tapped the broken pieces of the cover plate into alignment with a machining hammer, and traced the outline of the plate onto the scrap metal.

Then out came the trusty angle grinder to cut out the blank replacement plate.

After cutting out, I clamped the original to the duplicate and got the fit exact with the oldest machine tool known to man: the file.

This is the same method those ancient machinists used to cut the gears on the Antikythera mechanism. It isn’t as sexy or fast as modern machining, but it still works—and when you want decent precision at an affordable price, you can’t beat the humble file.

Once I had the profiles exactly matched, I used my spring-loaded center punch to mark the holes…

And then moved on to the drill press to punch all four holes into the blank.

With that done, I needed to weld a nut to the center hole to secure the tensioner bolt—and it had to be on the outside. On any asymmetric part, you want to be careful about making mods on the wrong side (lest you have to start over), so after I prepped it for welding I added a bit of insurance.

As you can see from the photos, I had a good match between the two parts—so it was time to destroy the old part to get the retaining nut out, which I then welded to the new part.

Then it was up on the wires for a paint job…

…while I lubed up the gears.

After that, all I had to do was assemble and mount the thing, clean out the twier in my forge, and give it a test fire.

It works!

Which means I’ve been busting my ass to fill the order on these pins (a few units of each style):

So, that’s that. One more feather on the pile of evidence that you can fix almost anything if you’ve got some creativity, a few basic tools, and aren’t afraid to use either.

And, as you may have gathered from the cross-post earlier in this article, I’m open for business for forge projects, audio/video production, strategic consulting, copywriting, research projects, and writing/reading/rhetoric/creativity mentorship (click the link below for more details).

Take Me, I'm Yours

Well, it’s that time of year again. As the summer gets itself into full swing and the vacation-minded go on vacation, client work here at my mountaintop hideaway has once again started growing a bit thin.

Excepting pottery. Small electric kilns have been available since the mid-20th century.