The following is an article by my longtime Twitter/X interlocutor Martin Skold. Our conversations over the last several years have helped shape my understanding of events in our rapidly-unfolding epochal shift, and have informed many of the articles I’ve written for you here.

By the way, as is common here, the article is long enough that your email client may choke on it. Read the original at http://jdanielsawyer.sustack.com

Skold is a geopolitical strategist who holds a PhD in international relations from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. As my schedule allows, I have been working my way through his new book from Marine Corps University Press (adapted from his dissertation): The Race With No Finish Line: Assessing the Strategy of Regional Great Power Competition. I will be posting a review when I’ve sufficiently digested it (sometime this summer), but the TL;DR already is this:

If you want to understand the world at a macro level, you need to read this book.

Skold also holds degrees from Georgetown University, and has served in the US counterterrorism community and as a Republican Hill staffer for foreign policy. He provides frequent commentary on American statecraft, foreign policy, and geopolitics on his X account, @MartinSkold2.

He adapted this article from a thread on that account at my request. No matter your political leanings, this is background you need in order to plan for the next series of disruptive waves that are beginning to crash across the world economy.

So, without further ado, I proudly present the most disturbing article you’ll read this month.

A Dilemma About A Dilemma:

The Paradox of Trying to Reindustrialize While Preserving Dollar Dominance

by Martin Skold

Sometimes hard choices must be made. Bankruptcies are replete with them; national bankruptcies at least as much so.

We are frequently told that the Trump Administration is interested in revitalizing American industry (either as a promise to voters or as a means of rebuilding US military power).

We are also told that the Administration is alarmed by the prospect of the loss of global dollar dominance and the borrowing power it enables, a loss which would precipitate a domestic fiscal crisis (either spiking inflation or enforced tightening of government spending with a corresponding economic contraction – or a Hobson’s choice between them).

What we are perhaps not ready for (though it is a subject of interest in geopolitical and financial circles) is the likelihood that we will have to choose between solving these problems – between rebuilding American industrial power and saving the dollar and the Rules-Based Order it is said to underwrite.

The reason hides in plain sight, but its implications are often not grappled with. What follows is an attempt to look at at least some of them.

An Industrial Doomsday Clock

The basic problem with dollar dominance is that reserve currency status effectively starts a clock, via something known as the Triffin Dilemma.

The basic idea is that the thing you own ends up owning you. Reserve currency status subsidizes your own challengers and eats away at your industrial (and therefore military) power.

The Triffin Dilemma arises because the nature of a reserve currency is that everybody uses it - it’s a unit of account for other currency transactions (effectively a fixed point in space), a medium of exchange for them, hopefully a store of value, etc. It’s a currency to buy currencies. Everybody stores lots of it.

The problem is that these surpluses have to go somewhere. So the other countries invest them in reserve currency-denominated (I’m just going to say “dollar-denominated” from now on - it’s easier) assets.

Broadly speaking this amounts to two things that show up on the same side of the ledger: Dollar-denominated debt, and dollar-denominated equity. Lending and ownership.

The dollar-denominated debt turns into a drain on the US current account - it means we’re net-borrowing other people’s money. It can be restated as, we import more than we export and pay for it with borrowing. The dollar-denominated equity purchases in turn become a capital account surplus, which is the other side of this coin - meaning US assets are being sold in net terms to foreign buyers.1

At some level, these two things are the same: To run a current account deficit is by definition to run a capital account surplus, and the accounting logic behind it is that you are selling off assets to pay the bills you incur from borrowing money to buy more than you sell.

This means that being the reserve currency -inherently- (barring some really strange circumstances) means you are running a consumption-based economy, selling off your productive capital to borrow and consume, and importing more than you export.

From a thrift-and-hard-work, Protestant ethic standpoint, this already is problematic, and it’s not an accident that the last several decades have seen jeremiads2 about the loss of traditional values of saving, delayed gratification, careful risk management, and so forth – the system we are in actively disincentivizes those things.

But the real problem comes in the industrial realm: You’re the net importer, so somebody – who could easily be China (ahem) - is now a net exporter.

In effect, you’re selling off your own assets to subsidize other countries’ industry, including potentially your adversaries’.

So a clock is running: In the beginning, it’s good to be the king, but over time - and sooner than you may think - you don’t have enough industry to support your global military commitments. Walmart does well; your steel companies not so much.

We are now effectively at the bottom end of that cycle. We were able to coast for some time because the offshoring of US industry in the Cold War occurred amid a tight circle of US allies – communist ideology made the Soviet sphere a (sufficiently) separate trade bloc. When the US became a net steel importer at the end of the Eisenhower Administration, it imported its steel from staunch allies like Japan; even when, in the ‘80s, Japan was seen (however implausibly in retrospect) to be a potential US challenger, it still was not the main US adversary. The end of the Cold War and the trade decisions made in its wake – particularly the World Trade Organization – eliminated the barrier between the US and its potential adversaries, most famously now including China.

Subsidizing An Adversary

Probably the most dramatic and alarming proxy for this is US shipbuilding, which is a fraction of one percent of China’s. It is true that US was never a major global shipbuilder – prior to World War Two its share of global production hovered around 2-3 percent, a figure which spiked to more than 80 percent under wartime mobilization (in which – as will become a familiar refrain – other industry was deputized to make ships), picking up for the loss of European production, before settling postwar at about 14 percent. At present, however, a similar multiple of production via a crash program (if it were even possible) would leave the US with a global shipbuilding share a fraction of what it had before that wartime mobilization. When one is facing the Maritime Militia – hundreds of Chinese commercial vessels deputized at any given time from China’s overall fleet of many thousands, to carry arms in the service of the Chinese state, or just wreak havoc by fishing in adversaries’ waters and daring them to react – this obviously matters.

Steel production is another good one - it crashed in the ‘80s and recovered just a bit under the Trump 45 Administration, but not to where it was.

As noted, this is an old problem – the US became a net steel importer in 1959 – but the trend has not improved. At this exact moment the US sources a plurality of its steel imports from Mexico and Brazil, the latter a China fellow-traveler; the former heavily implicated in the US’ twin migrant and drug crises.

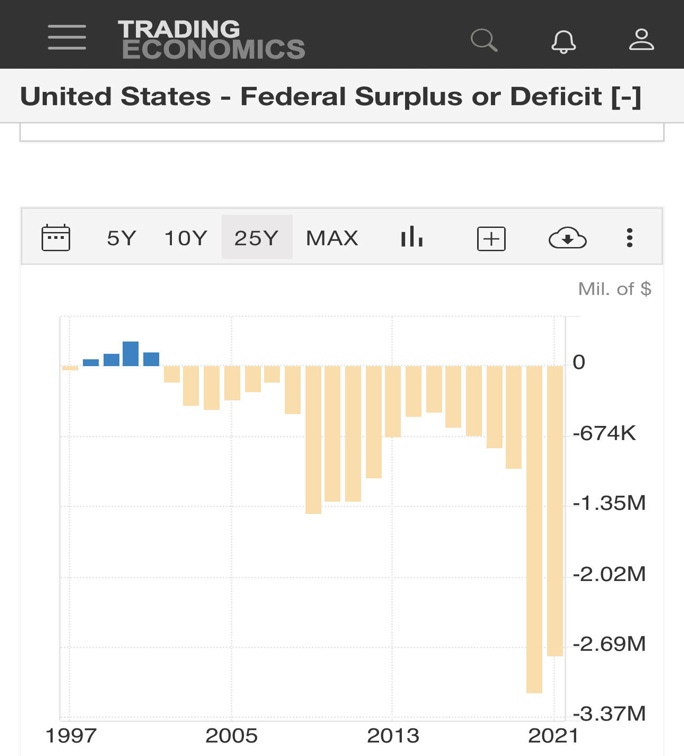

But the inverse general relationship between loss of manufacturing jobs and growth of (debt issuance-dependent) government jobs is also noteworthy – see the following chart from Volume One of Luke Gromen’s excellent and imaginative primer on the current global financial environment, The Mr. X Interviews:

There are other reasons for deindustrialization - overregulation (especially things like safety and environmental regulations), organized labor overreach, free trade itself – but they become marginal in a system where public finance itself effectively decrees industrial loss.

In effect, trying to reindustrialize without dealing with the trade deficit is like trying to stanch a firehose with a rag; trying to deal with it while keeping reserve currency status may be a case of Schrödinger’s Cake.

In fact, China in particular used to manipulate currency markets in order to suppress the renminbi (a.k.a. the Chinese Yuan) relative to the dollar to subsidize its exports when the market itself wasn’t doing it fast enough. But the market was at it all the same.

Lighting A (Paraffin) Fire Under Triffin

But the reason why the system is so intractable this time in particular is that the current reserve currency system revolves around the petrodollar system.3

Briefly, while the conventional narrative is that the inflation of the ‘70s, resulting from the one-two punch of abandonment of the gold standard and high oil prices, was eventually quelled by high interest rates & the crippling Volcker Recession (after Fed Chair Paul Volcker), a factor that may have been even more important was President Carter’s agreement with Saudi Arabia to price oil exclusively in dollars, which created an anchor for the dollar’s value by making it valuable for oil transactions - there would always be demand for it. (For a primer on this, I once again recommend Gromen’s book.)

This, in turn, funded “exorbitant privilege”4 – because everyone needed dollars to buy oil, demand for dollar-denominated securities was high and the US government in particular could borrow cheaply.5 And the fiscal deficit fed the current account deficit.

Sinking In The Sand

Almost as an aside, this is a major reason why the US has never been able to leave the Middle East.

Any threat to Saudi Arabia’s existence threatened that system and therefore threatened to bring back inflation, so (by one reading of the tea leaves, anyway) we were incentivized into Gulf War I.

On this point, it is true we cannot say for certain: We don’t know what HW Bush was actually thinking when he famously (and possibly impulsively) took on Saddam Hussein, but “Don’t be Carter” would have been at the back of his mind, and as a shrewd businessman and former CIA director, with the attendant geopolitical knowledge, he would have made the connection. Allowing Saudi Arabia to fall to an arrogant empire builder (a real possibility at the time of Operation Desert Shield) would have meant no one left to guarantee that oil would be priced in dollars – the resulting uncertainty would have been as good as a devaluation and brought inflation – never fully controlled – roaring back.

The Gulf War is often portrayed in trade terms – supposedly, the disruption of Gulf oil sales due to an Iraqi takeover of Saudi Arabia would have harmed the US economy, as in the 1970s. But a financial component redolent of that decade – the need to keep the otherwise floating dollar backed by oil – would logically have played a role, and possible a bigger one.6

Of course, once embedded in Iraq, we were stuck. We tried to solve it by killing Saddam; we got bogged down in a war of occupation and attendant regional politics even further. And of course, occupying Saudi Arabia also provoked the rise of Al Qaeda and 9/11, so that didn’t help either.

But it is noteworthy that, just as reserve currency status creates large deposits of dollars that have to go somewhere, the petrodollar system in particular created big pools of dollars in the petroleum-producing Gulf regimes themselves, in time to include not only Saudi Arabia, but also Qatar and UAE. A tiny amount of that - a pittance, really - went to funding grants for US foreign policy think-tanks.

It amounted to an agency-capture of US foreign policy: All of these think-tanks fed, and were a revolving door for, the political appointee-level positions in multiple administrations - and they could only recruit people who were willing to speak well of their benefactors. Which in turn means US foreign policy think-tanks will always have a reason to advocate more engagement in the Gulf.

The current round of US reserve currency status, therefore, almost of its nature requires us to be deeply embedded in the Persian Gulf. And this, in turn, is getting tricky, because of the aforementioned industrial issue: The Navy isn’t big enough to handle that and the Pacific and the Western Hemisphere. Something has to give.

It’s argued, anyhow, that the Trump tariffs themselves, if actually carried through, amount to strategic dollar devaluation. But however you choose to do the accounting, it should come out about the same: The petrodollar system and the dollar’s reserve status have to be up for discussion because the system that sustains them is about to go critical.

As to that, Saudi Arabia officially ended the petrodollar agreement last year – it still prices oil in dollars but reserves the right not to.

Borrowing Power On Borrowed Time

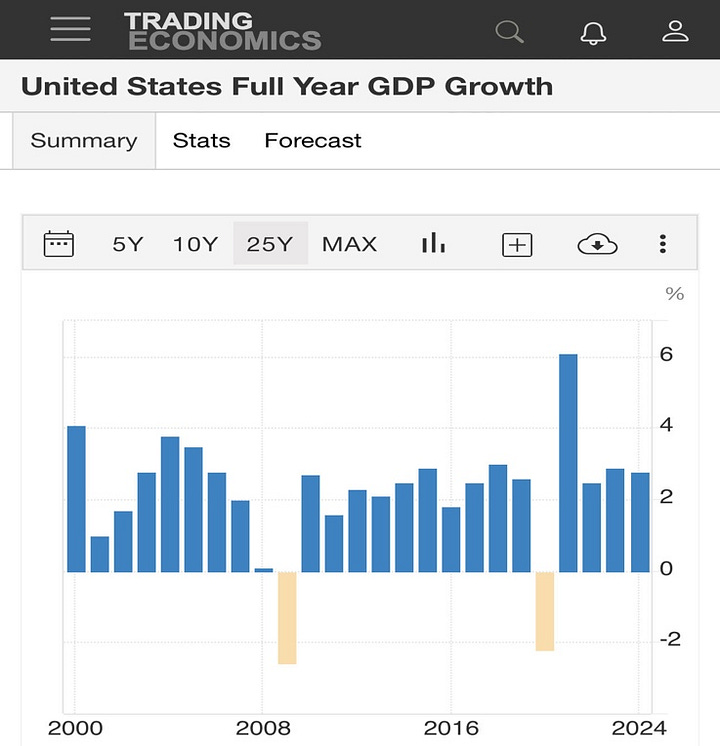

Conversely, the US’ finances are famously bad: Its entitlements fiscal gap - the difference between what it owes its elderly in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid and what it can reasonably be expected to take in - is in the tens of trillions – 100 percent or more of our gdp. Nobody is sure what the real number is, because it’s essentially unpayable, and it represents a shadow debt larger than the current national debt, made up of obligations that cannot be inflated away yet because they haven’t been borrowed yet (and therefore effectively track inflation).

But if you added up Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, the defense budget, and US debt service at this moment, all by themselves they nearly exceed the ~$4.9 trillion the US government receives in annual revenue, with the three entitlements costing $3 trillion between them, twice what they cost 15 years ago. And the Boomers are not even all retired yet, much less needing end-of-life care.

What does this mean for the petrodollar system and the dollar’s reserve status? Simple: Markets choke on our debt now.

Because there is not enough demand for the amount of US federal debt being issued even within this system, the Fed and Treasury must print money to take it off the market to keep interest rates from spiking. (Remember, when bond demand falls, all else equal, bond prices fall, and interest rates go -up- when that happens because the bond is now worth more at maturity relative to what you paid for it. It’s another way of saying people charge you more to lend to you.)

Except…when they do that, the dollar inflates – all else equal, more dollars on the market means a dollar buys less and prices rise. Including the price of a barrel of oil.

To buy oil, countries need more dollars, so exchange rates collapse – demand for dollars goes up, so they need to spend more of their currencies to buy the same amount of dollars to in turn spend more of those dollars on oil. To keep their currencies from falling too much, their banks sell dollar-denominated securities to buy dollars to take their own currencies off the market, creating relative scarcity of supply that bids up the exchange rate. Which means more US debt ends up back on the market. And then interest rates rise. And then more printing is needed.

This has happened multiple times in the last 5 or so years, and at some point a major oil producer is going to break the system and start offering oil in other currencies. Russia already has, as the US sanctions from Ukraine effectively locked them out of the banking system and accelerated their search for an alternative. If that goes mainstream, at that point, the petrodollar is done. And it could happen fast, though we don’t know quite when.

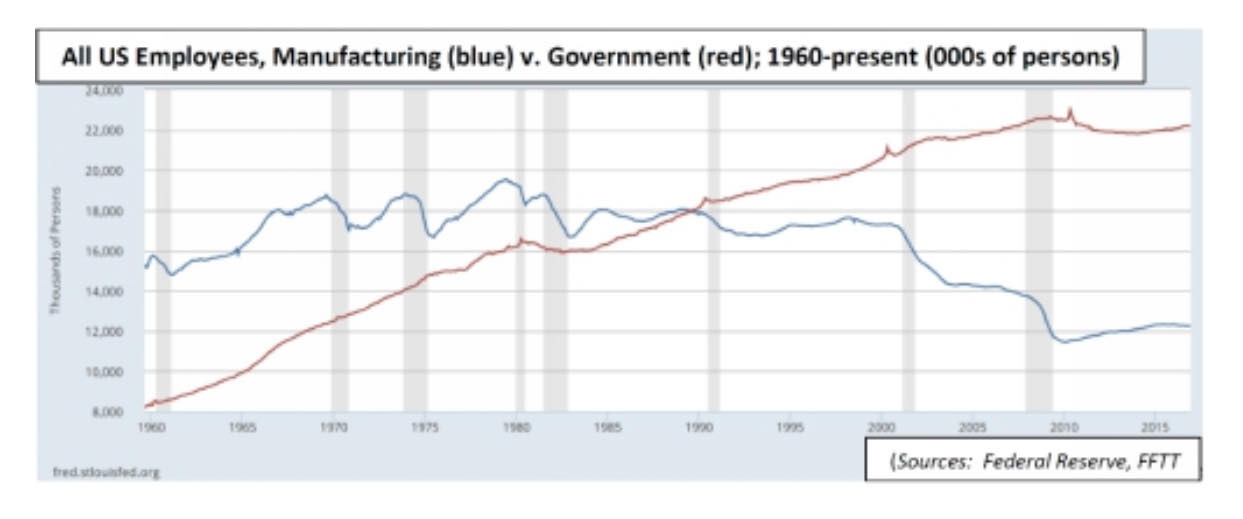

It gets worse: The US is now trapped in its own entitlements system. It has a weak, low-growth, overindebted economy (remember how that current account deficit means you’re borrowing to buy stuff - part of the equation) whose banks are now constantly on the verge of failure because of the aforementioned debt market vulnerability: When too much debt hits the market and the price falls rapidly, banks holding putatively safe US treasuries to comply with legal requirements take hits to their balance sheets…which they solve by selling treasuries for liquidity, exacerbating the problem. The US banking sector has been propped up by Fed liquidity since 2023, when this phenomenon caused a run on Silicon Valley Bank, leading to the subsequent run on First Republic Bank and a barely averted systemic crisis.

An abrupt cut in deficit spending may cause a recession, depending on how fast money gets lent to the private sector instead of Uncle Sam. If that happens, it may hit the banks, perhaps by exacerbating their existing liquidity troubles, as per the above. But in truth, the US is already so overindebted it now has mounting credit card defaults, carefully hidden mortgage defaults, and a mountain of corporate debt. A financial crisis, if one comes, will be overdetermined.

Credit may seize up as in 2008. The remedy for that is more printing. You know what that means.

And either way, a recession means falling tax revenues, which defaults (forgive me) to more borrowing and printing.

We can file this under “maybe,” because there is a recent case study in it not happening: The “fiscal cliff” of 2013, where the expiration of tax cuts led to a precipitous fall in deficit spending that was supposed to hit gdp but apparently did not.

As of this writing, market turmoil is being blamed variously on the Administration’s tariff policy and on the Department Of Government Efficiency (DOGE) cuts – ie, on either trade or financial policy, but no one is sure which. This conflation should sound familiar by now.

Regardless, though, the above should make clear two things. First, the US is addicted to debt, to the point where it is financing debts with other debts. If it were a corporation, it would be a zombie corporation – able to finance its operations but not to pay off principal, and hugely dependent on liquidity. And secondly, the time when that system can sustain itself is, because of the very nature of that system, about to end.

We may have an opportunity to conduct a controlled demolition of the petrodollar system (though it is noteworthy that it is fundamentally controlled from abroad), or others may do it for us. But it is not built to last, and relying on it has, as shown, become not only hugely dangerous but – because there is little to be done now – an historic tragedy.

Out Of Our Hands

If you’ve concluded by now that the petrodollar system is a dangerous liability that is also about to hit a critical state, you’ve gotten the main point, but there is more. China is not going to make the same mistake we did, and it is putting the pieces in place to end the current system on its terms – quite possibly at the moment least favorable to us.

For better and worse, China is already trying to square the circle of the Triffin Dilemma by experimenting with a global multi-currency system. It appears they first attempted this when Xi came to power, briefly pegging the IMF’s Special Drawing Right - a basket of important currencies used as a unit of account for certain international banking purposes - to gold.7

This could, in turn, become the basis for a multi-currency commodities regime where a consortium of currencies floated in a collective band relative to gold and all usable to buy oil. It’s an old idea, known as a bancor. And it’s sufficiently in the mainstream to at least be a topic of conversation. Whatever the pros or cons of such a system, China appears to be at least readying it.

Dilemmas Within Dilemmas

Which raises the question: Isn’t that bad for us? Well yes – they want our inflation to spike and hurt us further…but if we need industry anyway, we don’t have a lot of choice.

That assumes, of course, that reversing the current account deficit brings back heavy industry, of a type in particular that might be usable for defense. It might lead to any number of things, inasmuch as “exports” can be a flexible term, and given especially that the US does not necessarily have an industrial base any longer that can immediately be built upon. Most machinists come from generations preceding the Millennials. It is also possible that, far from reversing the current account deficit, let alone bringing back US industry, the end of the petrodollar will simply lead to a record asset selloff.

It’s somewhat likely, in fact, that as industrial knowledge has disappeared, direct subsidies for training and the like will be necessary to get it back. Think of it as student loans, but for machinists and welders. Or call it by its Russian name: Perestroika – “Restructuring.”

Whatever the case, though, it’s far from clear there’s a way out of our industrial malaise except through a currency maelstrom – and then only if conditions are right.

Think of proposals that US Steel be sold to Japanese investors.

Definition: A lament about, or prophecy of, doom

Of note: Yes, this system gets called a number of things - petrodollar, eurodollar, etc and yes, its facets change over time. For these purposes, “petrodollar” will do.

Editor’s (i.e. Dan’s) note: A term of art referring to the different ecological constraints which give holder of the world reserve currency latitude-of-policy and action that non-reserve currency nations lack.

This is disputed by the well-renowned financial and economic analyst Michael Pettis, who discusses it here. Suffice it to say, despite my great respect for Pettis’ analysis, I do not find this assertion entirely dispositive on face. He is assuredly right that China in particular is structurally obliged to export capital, and that this drives some of the US’ legendary (and maligned) borrowing power – but the petrodollar undoubtedly plays a major role as well. In any case, the reader may judge.

Editor’s note: This point supports a number of the conclusions I advanced in Lifting the Veil (as does much else in this article).

I'm old enough to remember when the USA had a positive balance of trade. I remember that, as it went into negative numbers, we were told that it was a good thing. I remember thinking, 'what, are you crazy'? I remember NAFTA, and Ross Perot telling us there would be a 'giant sucking sound' of American jobs going to Mexico.

After all these years, I can only conclude that our experts are idiots.

Yep. Yep. Yep. I think they are gearing up for a restructuring. I have gold. I have crypto. I haven't trusted the dollar for a while now. We have to start manufacturing necessities (medication, war machines, food, shelter) in-house. We just do. The market has been over-producing for way too long so the slow down has to happen. It sucks because our money wasn't handled responsibly and people are still upset we have to cut. We cant pay the bills. I've never seen so many people just refuse to acknowledge the truth. Thanks much for sharing.