Reminder: I’m currently in a scramble for new clients due to a financial gut-punch a few weeks ago. If you need someone to do for you the things that I do (the list is long but distinguished), there’s never been a better time to take advantage of me! Hit me up at dan at jdsawyer dot net

This article is long and may not display correctly in your email client. You can read it on the web at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com

It works for romance novels and erotica.

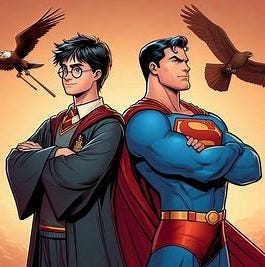

It worked for Twilight.

It worked for Harry Potter.

It worked for Disney Star Wars movies (well, kind-of, for a while).

Formulate a main character without rough edges, without defining flaws or passions,1 and you can basically trick an audience into going along for the ride. They will merrily strap your main character on like a skin-suit and walk them around, and never once have to face any difficulties about the tragic implications of hubris, or struggles for growth, or—and this part is important—finding themselves disappointed by the POV character’s choices or actions.

Yeah, sure, okay, the audience might find the story to be a bit of a let-down because it packs less dramatic punch than one with a proper, complex hero, but that doesn’t matter—they still buy what you’re selling, and it sells to more people if you give them a blank slate on which to project themselves.

This kind of character is often called a “Mary Sue,” but that’s not technically correct. A Mary Sue2 is an overpowered and underflawed author insert who faces no serious obstacles because the plot is on her side, but the Mary Sue is but a single variation of this broader character type that has risen, once again, to prominence in recent decades.

Nor are we talking about a thinly-narrated NPC. The NPC is a Non-Player Character in a video game—an artificial construct, controlled by the AI, which serves purely to move the action along. Their defining feature is that they have no apparent consciousness. Zombies, computer readouts, the demon-possessed, animatronic dolls, religious dogmatists, and people who watch the news are NPCs.

No, the phenomenon I’m describing here is the opposite of the NPC:

The Player-Character.

The Player-Character

In any video game, the Player-Character must be one into whom the audience is willing to pour their identity—so it should have as little identity of its own as possible, and contain features that are either identifiable (i.e. the audience says “hey, that’s like me!”) or aspirational (i.e. the audience says “hey, that’s like who I wanna be!”), rather than well-drawn and complex.

Importantly, a Player-Character is not a “Main Character.”

A Main Character has a nature, a personality, strengths, weaknesses, flaws, and a gestalt feel about who they are based on all of these qualities. You know who Frodo is (though which Frodo you know will depend on where you know him from), so you sympathize with him (or dislike him), but you don’t identify with him in the same way you might with, for example, Harry Potter or Bella Swan.

Both of these latter characters have features (desires, talents, destiny, etc). and they may even have flaws (Harry’s self-righteousness, Bella’s self-abrogation), but neither their flaws nor their features are definitive—i.e. they are not things which set them apart from their audience (or at least from who their audience fancies themselves to be). Both of these characters, for example, have no accomplishments—Harry’s talents and Bella’s beauty are endowed upon them by accidents of birth (or early childhood) and history—because, as odd as it seems, if they had to struggle to overcome themselves and obstacles greater than they could handle, it might not play well to the audience.

Their near-perfection (in the strange sense that they each separately embody it) is the chief reason for their appeal to audiences who fancy themselves oppressed.

The Paradox of Perfection

Barmy, right? The reason so many people hate the Star Wars sequel series, after all, is because Rey is exactly this kind of character. She’s so perfect that she has nothing to offer the audience. Especially if that audience is looking for escape, inspiration, and hope during dark times. Perfection is unattainable, and, as we all learn in literary boot camp, the struggles of a hero or heroine3 to grow, overcome, and triumph are what makes the story endure for the reader.

There’s a reason this mode of storytelling has persisted for thousands of years—it fits how our minds work.

You might therefore think that a perfect character would be unappealing, especially to people in search of inspiration and escape, but a quick glance at the history of narrative reveals a paradox:

The more all-powerful, untouchable, and…well…inhuman the hero, the more appealing he or she is to a particular kind of audience.

Superman was created in 1932 by a pair of teenage Jewish science fiction geeks, and underwent a few iterations as he moved from a Nietzschean scientific ubermensch to his final form that we’re all familiar with at the end of the 30s.

As Hitler and Stalin carried out protracted pogroms against God’s Chosen People, while the United States and England gleefully refused Jewish refugees from the conflict zone, the Jewish self-conception was on the rocks. A savior was needed. So the most high El4 (well, Jor-El, anyway) would send his son Kal-El to work miracles, destroy the enemies of the Jews (like Nazis and the KKK and the gangsters that were destroying the Jewish community in New York), and restore goodness and justice and a sense of idealism to the world. The messiah the Jewish people had been long awaiting was come at last, in comic-book form, and the weary world—Jewish and Christian alike—made him a star.

My partner and I are currently seeking gigs for editorial, layout/design, voice over, audiobook narration, and strategic consulting work. Additionally, if you’re looking for a tutor for a student struggling with history, English, creative writing, or psychology, I’m available for hire.

Or you can help out substantially by joining me here as a paid subscriber.

Such distant, superhuman or inhuman characters grow out of subcultures where hope is thin on the ground. Overpowered, innately talented, relatively flawless “heroes” have always appealed primarily to children and to adults who were terribly abused or neglected as children because they meet that same need that Superman did in a world in the midst of an economic depression and long-gathering clouds of war with totalitarians springing up at every front:

They don’t provide aspiration, or even inspiration.

They provide consolation.

The ultimate dream—the savoir or god who will save us, or who we secretly might discover ourselves to be—is a power fantasy, appealing to the powerless. Its appeal lies chiefly in the fact that it is unattainable, but not implausible. It vests its impossible hope just over the horizon, allowing it to light up the world with pre-dawn gray.

Their unrealism is the point.

Harry will vanquish Voldemort!

Look—up in the sky—it’s Superman!

The Corn King will bring the crops again!

Capitalism is finally succumbing to its contradictions!

Jesus is coming back!

For the powerless, the best story is of a redeemer, not a hero.

Which is a hell of a shame.

What, Then of Heroes?

Aristocrats, tradesmen, freeholders, and other people on the make don’t usually gravitate towards redeemers. They instead seek out heroes.

Samson. Odysseus. Augustus. Robin Hood. Arthur. Aladdin. Prometheus Oedipus. Einstein. Achilles. Isis. Marlowe.

Whether fictional, mythical, or based in history, heroes are great figures who battle the gods, who wrestle with fate, who battle their own flaws, who put together alliances, who are undone by hubris, who are often complex and difficult (in both a moral and a social sense).

For heroes (and heroines), the defining feature is not their goodness, nor their sin, nor their exemplary embodiment of this or that noble virtue, or even their great (and terrible) deeds, it’s their determination to rule their own life. This determination appeals to that audience I mentioned at the beginning of this section because for such people to survive, they must be self-possessed. The tradesman, the aristocrat, the freeholder, the wildcatter, the extreme sportsman, the hunter, the craftsman, and the warrior all live lives where, at least occasionally, they must be willing to force the world to behave itself—or they go bust. For such people self-possession is the ground condition of acceptable being.

People on the make look to heroic figures for inspiration (“If Odysseus can face the Sirens, then I can face this”), for aspiration (“If I could just have the patience and persistence of Job, I could get through this rough patch”), as well as for consolation when their own struggles result in a loss (“It’s not so bad. King Arthur’s wife cheated on him, too.”).

Such notions are of no use whatever to the hopeless, a lesson I learned the hard way when I was prepping my volume The Secrets of the Heinlein Juvenile for publication.

Secrets looks at American Children’s literature, concentrating on a set of books that combined some of the oldest Western storytelling traditions and some of the most quintessentially American traditions into a literary form that re-made the face of the twentieth century (literally).

One of my longtime beta readers, a millennial who was proofing the book, contacted me in a rage to tell me he was quitting my reading staff and he wasn’t sure he wanted to be my friend anymore.

The book, it seemed, had offended him.

By “offended” I don’t mean “he got his knickers in a twist because I stepped on a social taboo.” I mean “his sense of right and wrong in the universe was gravely disturbed.”

And it wasn’t my words that had upset him; it was reading the summaries of the struggles of the heroes in the books I was studying.

It was a cruel joke, he held, to suggest that anyone should fight against the odds faced by the characters in these books. Nobody in their right mind would bother. He took it as a personal affront that I—I who had known so many downtrodden people, who had been through years of abuse and misery myself—could possibly hold that giving children such heroes to read about would do anything but make them suicidal.

Nobody in real life had anything like the kind of courage or self-possession portrayed in these books—real people, in his estimation, were just lost, and needed saving, and deserved to be saved, and anyone who disagreed was either too stupid or too cruel to be worth talking to.

Extreme reaction?

Sure.

But that’s what happens when someone, even unintentionally, steps on your buttons.

American Tales

You didn’t used to see a lot of heroes like Superman in the American literary canon. Yeah, Hawk-eye5 is a master tracker, and Huck Finn is a consummate juvenile trouble-evader, and Davy Crockett could do almost anything he wanted, but none of them are inhumanly grand.

The closest you’ll find, at least before the Progressive Era, is the Tall Tale tradition, and most of these characters6—who bordered on being a superheroes—were either transparent parodic metaphors or cartoon-amplified versions of real life badassery. That is, in no small part, because of the kind of place America was up until the twentieth century:

It was a country of doers. Immigrants. Tradesmen. Captains of industry. Pioneers and homesteaders. Architects and itinerant showmen. Traveling laborers. Hobos. People who owned their own destiny.

Heroes inspire the self-possessed. But they intimidate people who believe they are victims, because they shine the light on their own reticence to face their pain and fear—and to save themselves.

And that provides an unexpected trick for understanding one’s place in history.

Taking the Social Temperature

In his gripping autobiography Becoming Superman,7 J. Michael Straczynski tells of the strange road that brought him to Hollywood. He spins a yarn of dark family secrets stretching back to World War Two, of murder mysteries that took him over six decades to unravel, of being isolated in a home dominated by monsters, and how comic books literally saved his life.

Genre tales were the hope in a hopeless situation, the heart in a heartless world, the moral instruction he desperately longed for. They were the consolation of his downtrodden soul. They were his opiate, and his masses.

And, long after he failed to find solace in any church, they remained his religion.

Isolated both by his family’s darkness (and his own consequent dysfunctions) and by his intellect, he found in the illuminated comic-book pages the tales of those special-but-downtrodden souls who took responsibility for their inborn power to save others (and thus, themselves). These themes dominate his work—from his comic book serials to his magnum opus Babylon 5—to this day.

They also limit it, for rarely in Straczynski’s oeuvre do you find fully realized heroes. Every other sort of character appears in abundance—jarhead, bureaucrat, victim, determined survivor, well-intentioned villain, inscrutable wizard, amoral powerbroker, ideological warrior, mission-driven caregiver, star-crossed lover, and self-sacrificing martyr—but you will almost never quite find a hero like Henry V or Achilles or Conan: self-directed, goal-focused, and moving with purpose that doesn’t involve directly serving a “greater good” which has been defined by an authority figure.

Then again, we haven’t seen many heroes like that in literature or film in quite a while. And this is no accident.

There is, of course, a feedback loop effect—the audience hooked on redeemers craves more redeemers to console them in their powerlessness—but the root cause of the spiritual and aesthetic8 fashions of the day is reality itself.

A growing, healthy civilization hungers for and generates heroes, both real and mythical. The people in such a world lift their gaze from their daily toil and stare into the stars, and think “If I can build a house with these hands, if I build long enough, I can climb to the heavens.”

The sigh of the oppressed people longs for a redeemer, and when their gaze lifts to the heavens it is only to ask “From whence cometh my help?” It is a question that provides its own answer, for it advertises a market. Redeemers materialize in endless procession.

They sell healing from the television for the cost of a small donation and a prayer.

They’ll take away your boredom for the cost of a game of chance—or of skill.

The next technological innovation will save the economy, remake the world, and cure Mom’s arthritis.

The rising revolutionary tide will fix the fertility crisis and all the disaffected young men will finally be able to get laid (and the girls…well, they’ll do what they’re told, won’t they? Women are compliant by nature, after all).

The Triumph of the Player-Character

We are now hurtling headlong into the second election season in a row where one party has decided to conduct itself as if its candidate is a Player-Character. This party is not running its candidate, but is instead keeping that candidate hidden away so that the chattering classes can craft that Player-Character’s story and image to suit the needs of the moment. The fewer public appearances the Player-Character makes, the better, because any flaws that the Character displays might disrupt the projection of individual voters’ fantasies about what they want out of a leader.

And on the other side? Well, there’s a difficult character over there, but he’s difficult in the kinds of ways that are, to his base, relatable. Consoling, even. He is, in his own way, as generic and empty as the quasi-incumbent.

The fact that these two skin-suit characters seem—at least at the moment—to be closely matched against one another give us our location in the American civilizational cycle:

The majority of people are tired of the corruption and dysfunction in the current iteration of the American system.

But many of that majority are afraid to let go of the old system for fear that something worse may replace it.9

What we’re seeing, in other words, is not an electoral contest in which a hollow shell Player-Character stands against a vital opposition party led by a hero, behind whom are united supporters who are willing to march shoulder-to-shoulder, to stand for schoolboard elections, to run county commissions, to clean up their local parks, and to bring the voice of the new vision to actually fix a badly broken national system.

What we instead have are two major parties who have each fielded Player-Character redeemers. “I will save you from the ruling class!” says one, while the other promises “I will save you from the revolutionaries!”

If you look around and find a world inundated with saviors and the thirst for salvation, you’re in a dying culture.

Holding Out for a Hero

Nobody wants to be a hero.

Heroes meet sticky ends.

They might wind up friendless.

They might wind up broke.

They might wind up in prison.

They might wind up dead.10

Nobody wants a hero, either.

A hero might embarrass you into actually seizing control of your own life.

Much better, in the end, to look for someone to serve as a vessel of hope.

Because that’s what hopeless, demoralized, slaves do.

But if you watch the horizon, you might eventually detect a glimmer of light.

When your culture starts once again craving struggling heroes in its fiction; when it again craves angels with dirty faces who offend detractors with their pig-headedness and embarrass fans with their persistence, who bleed for their victories (and who don’t always win), who put their asses on the line…then, and only then, will someone capable of turning over the system into something healthy become electable.

Until then, I’ll keep writing heroes who wrestle the gods.

If you’re looking for fresh stories, you can find my novels, short stories, visions, and dreams (along with some how-to books and literary studies) by clicking here.

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. If you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

This column is a big part of how I make my living—bigger now due to recent exciting events which you can read about here. Because of this, I’m offering a 20% lifetime discount off the annual subscription rate. If you’re finding these articles valuable, I’d be honored to have you join the ranks of my supporters!

A “defining” feature is here used to contrast with a “generic” feature. A character who gets hungry because food is necessary to live doesn’t have a “defining” feature. A character who is obsessed with Marmite because only that strange brown brewer’s goo will satisfy her appetite has a “defining” feature.

Or Gary Stu, if it’s a dude.

There are distinct, but complimentary, literary traditions for heroes and heroines. I tackle them in my book The Secrets of the Heinlein Juvenile, and they can be found explored separately in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces (for heroes) and Gail Carriger’s The Heroine’s Journey (for heroines).

El Elyon—literally “God Most High”—is one of the many dozens of Biblical titles of and/or names for God (for reasons too complicated to get into here).

The one from The Last of the Mohicans, not the comic book character.

Such as Pecos Bill, John Henry, Joe Magarac, and Paul Bunyan

Seriously, it’s a great book and I can’t recommend it enough.

…but I repeat myself…

And they may be right.

And if you doubt that, think of all the veterans you used to know.

Another enjoyable post, not the least because I recalled some of my favorite musical and cinematic memories.

Understanding the difference between hero and redeemer seems important for picking ones relationships. Though it seems like generally you'd use your ability to attract and maintain relationships (of any kind) with heros as a good barometer for your own bad-assery, there may be a time and place where one is in need of a redeemer. But I'd think the worst outcomes happen when we either aren't clear on what we want or need or have one expectation of someone who isn't going to give it (either outright refusal or inability)

I know this wasn't a music post but "holding out for a hero" is one of my all time favorite songs. The score to the Last of the Mohicans film is also, one of my all time favorites. (I used to listen to it before SPORTS games...as a TEENAGER, needless to say I had headphones for that one). LOTM also had one of the most intoxicating scenes I've seen on screen.