In this article, I’m going to be looking at what has become an article of faith among the vast majority of American citizens, and demonstrating that it’s an illusion. I don’t relish doing this, both for the hate mail it is likely to provoke and because I am very unhappy that the occasion demands it, but in my view the article of faith in question has become at least as dangerous as the danger it was meant to guard against.

Because of this, this article features several dozen links to online references, and footnotes about offline ones. All are worth delving into.

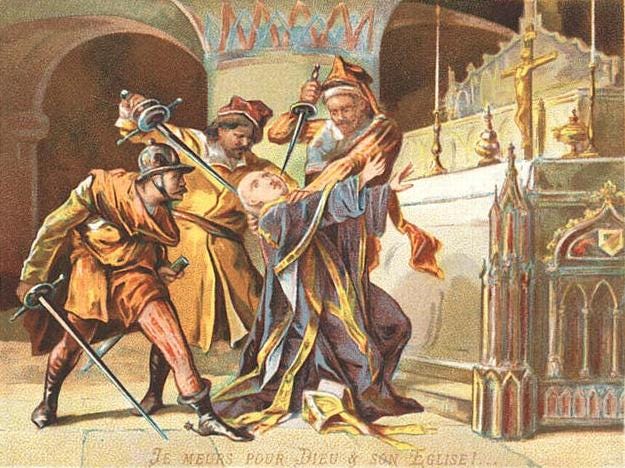

The Tale of the Troublesome Priest

Tom and Hank were inseparable. They started hanging out when they were teenagers, and spent a lot of time hunting and camping and drinking and carousing and chasing girls together. They were a terrible twosome that got away with all kinds of moderately disreputable shenanigans because Hank’s dad was rich, and nobody wanted to risk offending his son.

When Hank’s older cousin Steve fell ill he started trying to figure out what to do with the family business, and he realized that, even though Hank wasn’t the heir apparent, he was the only guy the Board of Directors would put up with as the new CEO. So, when Steve succumbed to his illness in Hank’s early twenties, Hank inherited the family business. He hired Tom on as CFO.

In the ensuing couple years as Hank learned the ropes and gained control of the company, he found himself in need of allies. When the head of the Compliance department vacated his position, Hank convinced Tom to take the job. The wrong man in that position that could cause Hank a lot of trouble, and Hank knew that Tom would always have his back.

Unfortunately for Hank, Tom was a conscientious sort, and once he felt the burden of responsibility he snapped-to, gave up the booze and stopped chasing tail, and started rooting out corruption in his department. This caused a lot of problems for Hank personally, and for the board members more generally, as everyone was, in one way or another, involved with some kind of shady dealings where the compliance department was concerned.

After several of the board members urged Hank to call out the mafia to get Tom knocked off, or at least find some way to fire him without violating his contract, Hank finally started to lean on Tom. But numerous, very personal arguments would not sway Tom’s sense of responsibility to the job that he was now honor-bound to perform, nor from his determination to extend the power of the compliance department at Hank’s expense.

In a fit of pique, Hank started ranting one night while some of his ambitious bodyguards were in the room. During the rant, he wished that somebody would just get rid of Tom so that he didn’t have to deal with the problem anymore.

The bodyguards listened.

After hearing his boss shout “Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?!,”1 four of the guards proceeded from the castle of King Henry II of England to the Cathedral of Canterbury, whereupon they found Archbishop Thomas Beckett chanting vespers. As he chanted, they seized him, scalped him, beat him, and beheaded him when he refused to change his mind.

Comforting Rhetoric

I know those of you born later are probably tired of hearing about it, but for all its problems, the end of the Cold War era was a great time to be alive. It was an unusually quiet time, both domestically and internationally. In all the years of the Reagan administration, there was only one foreign military adventure: the invasion of Grenada. And it lasted one weekend. The Boomer generation, who had fought in Vietnam, controlled the ballot box (as they still do), and at the time they were tired of war. My generation (Gen X) never had to face the draft, because our parents were never willing to elect someone who might resurrect it.

It was an era of relative domestic tranquility (which spawned its own problems, but hey, life’s full of trade-offs), without major riots or other civil unrest beyond the occasional gang war. In a country the size of the United States, that’s saying a hell of a lot.

In such an environment, you can imagine how common-sensical it seemed to learn in civics class (we still had those back then) that the defining quality of American Democracy is:

“The peaceful transfer of power.”

This, we were told, is what defines the American political system. The entire point of the system is to stabilize the country as governments turn over—something not guaranteed in monarchies (or even parliamentary democracies), but that has been the hallmark of American Constitutional democracy.

It was our creed. One that I heard repeated like a shibboleth on every inauguration day of my life (excepting in 2021).

Political violence, we were taught to believe, was unacceptable. It would plunge us into chaos and anarchy, or at the very least another civil war (once was enough, thank you!). It was the kind of thing that happened in Banana Republics,2 not in the United States of America. We are better than that, goddammit!

Sure, okay, yeah, we’ve had the occasional bad year—or bad decade—but the random politically-motivated social violence (such as the riots and bombing campaigns in the summer of 1969) and actual political violence intended to subvert elections are different things, aren’t they?

It has been a sacred totem of the American political consciousness that, while other countries might have their revolutions, popular uprisings, and actual honest-to-God political warfare, we do not. The nature of our system is that, even though the US Presidency is the most powerful position in the world, and the kind of position anyone in any other country in history would kill to control, we don’t do that kind of thing.

Anywhere else, sure, but not here. We have a tradition of civility, and we must, at all costs, anathematize political violence—it is the one kind of violence we must not be seen to tolerate. It is totally unacceptable.

The United States is a peace-loving nation, dedicated to good-faith disputation and solving our deeply-felt disagreements peacefully and spreading that ethic across the globe.

That’s what we were taught.

It’s what we believed.

But here’s the problem:

It isn’t true.

And it never has been.

America the Pugilistic

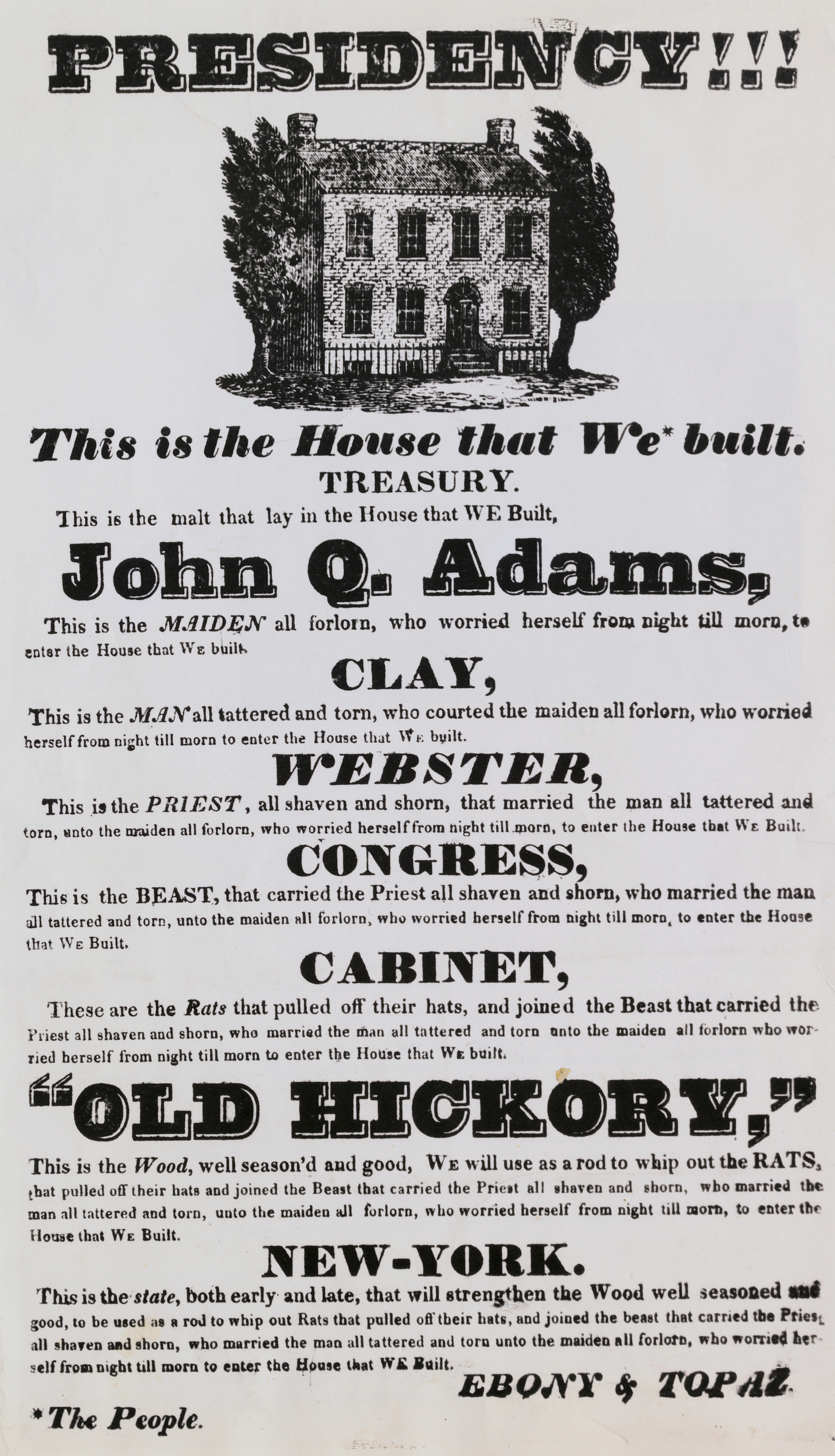

Blood-and-guts rhetoric has always been a part of the American political discourse. The pre-Civil War era saw Presidential aspirants, cabinet members, and other politicians employ everything from dueling to dick jokes.

Personal disputes between Senators have, more than once, led to violence (including fistfights, gun fights, brawls, and beatings) in the Capitol building.

As we will explore below, the United States of America has never been a peaceful country. We were born in war, completed in conquest, and plagued by rebellions and border wars for much of our history. All told, the U.S has been at war for most of the years it has existed, often conducting two or three wars at a time (especially if you count covert wars, several of which I will mention later).

But, in its rough-and-tumble nature, the United States is not alone. All countries are born in war, maintained through violence, and managed by the threat of violence.

All countries.

Everywhere.

Always.

Those of us who live beneath the blanket secured by violence, or who are subjected to the fist of the state cloaked in the boxing gloves of administrative procedure often allow ourselves to forget this simple, unbearably harsh fact of life.

But our ability to pretend that we live in such a world is changing.

Where We Are

“Once is happenstance. Twice is coincidence. Three times is enemy action.”

—Ian Fleming, Goldfinger

In the novel Goldfinger, the above line is attributed to the Chicago political machine. I’ve seen it pop up in other contexts, including the memoirs of spies who worked at Bletchley Park and in other parts of the British Secret Service in World War Two, where it appears to be an old heuristic from the British intelligence community (then again, they might have been quoting Fleming). Wherever it comes from, its usefulness as a heuristic is obvious:

When something disturbs the way you’re accustomed to seeing the world and you’re trying to figure out whether to take it seriously, observe its frequency.

PR claims to one side, violence has never been a stranger to the American political experience. Some group or another attacks the US Capitol or occupies one or another government building every few years with the object of stopping the machinery of government.

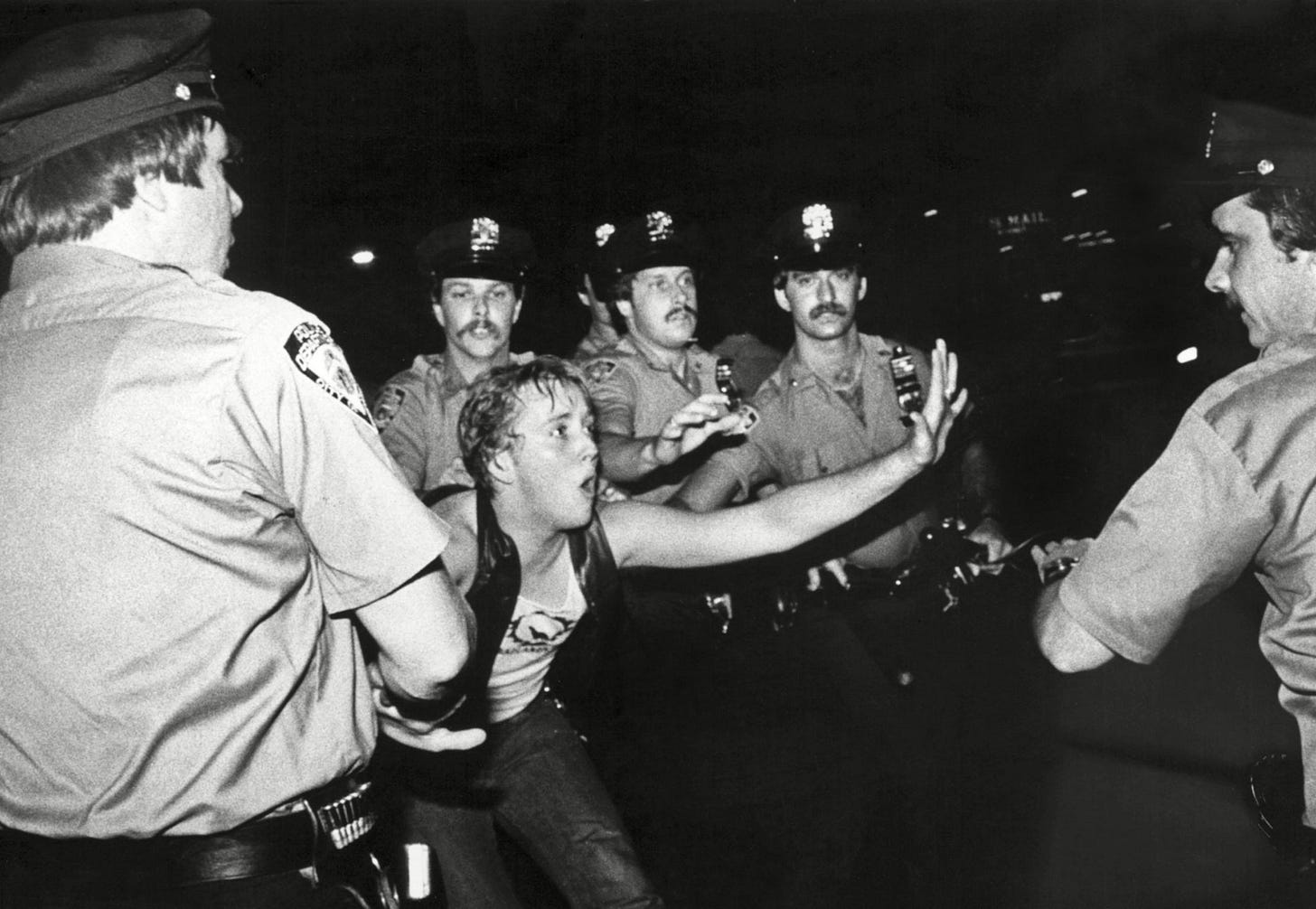

However, until recently, violence had not been commonly used either in retaliation for elections nor to influence elections in quite a number of decades (the events at the 1968 Democratic National Convention notwithstanding). In the Post-World War 2 era, political violence in America has usually been more diffuse: hired gangs beating up voters in the 1950s south, bomb threats and bombings aimed at increasing instability and calling the government into question, etc.

But very slowly, over the past three decades, something changed in the national consciousness.

First, the rhetoric changed. Starting with the election of Bill Clinton—who only received 43% of the popular vote due to a three-way Presidential race that year—every single election has met with public accusations of illegitimacy on one pretext or another. And, every time there’s a new election, we are also met with public assurances that election integrity in the United States is unquestionable (unless maybe the Supreme Court intervenes, as ultimately happened when Al Gore decided, to his detriment, to turn the 2000 Florida General election into a lawsuit).

Over the same period, normal colloquial American English (which is replete with firearms-related metaphors)3 gradually got popularly re-classified as “violent speech/incitement.”4 I first remember seeing this move coming from the campaign of Gabrielle Giffords, who was shot by a former supporter during a 2011 public appearance. Giffords’ staff subsequently blamed the shooting on Sarah Palin’s vice-presidential campaign, because it had released the following graphic about targeting specific Congressional seats for turnover in the 2012 general election:

Since the Clinton years, thanks partly to its embrace of global governance and trade, and partly to its championing of LGBT activism, the Democratic party has found the white working class (its historic base) harder and harder to woo. The gradual realignment of political parties that ensued provoked a kind of self-righteous indignation from the Democrat ruling class, with Barack Obama famously describing the working class center of the country as bitterly clinging to God and guns—remarks for which his opponent, Hillary Clinton, lambasted him.

Hillary Clinton herself, a few short years later, described the same people as a “basket of deplorables.” The people that both politicians were thusly describing, by the way, make up an election-swinging chunk of the American populace.

And we’ve all seen what’s happened since.

Trump called for Hillary’s imprisonment.

Hillary’s people called for Trump’s head, and eventually developed the now-persistent narrative that Trump was the second coming of Adolf Hitler.

And since then, the rhetoric has escalated, with everyone from obvious screeching lunatics (such as Keith Olberman and Stephen Crowder) to apparently sober-but-extremely-earnest voices who read to their audiences as reasonable and dispassionate (such as Sam Harris and Tucker Carlson) have taken regularly to declaring the impending End of America if the other side wins.

The “other side.”

If only those assholes weren’t in power.

If only they could be permanently kept out of power.

If only sanity and sober judgment could rule the day

If only the bad guys weren’t causing problems.

You can almost hear the clarion call:

Will no one rid us of these troublesome priests?

The Outlawing of Dissent

After World War 2, Presidents Truman and Eisenhower shifted the United States Government to a permanent war-time footing in order to fight the Cold War and advance related American interests around the globe. Information was fed to the public only through authorized, licensed news outlets, and underground newspapers and information networks run by those outside of the national Liberal Consensus (as it was then called) were targeted for infiltration, set-ups, and prosecution.

Dissenting groups of socialists and communists on one side, of radical right wingers (Klansmen, the John Birch Society, etc.), and of other outsiders (the Objectivist movement, the Libertarian movement, the gay community, the Nation of Islam, the Civil Rights movement, comic book artists, science fiction fandom, and the psychedelic movement) were routinely treated as breeding grounds for potential enemy combatants by the US National Security apparatus.

While the government steadily lost ground on free speech issues in the Supreme Court (which, especially during the Warren years did not recognize the government’s overriding wartime interest in suppressing these groups), the Court did not choose to curtail the infiltration, surveillance, and manipulation of these groups by government actors.

During this period the Federal Government (especially the military and the State Department) also conducted expansive programs of human experimentation on unwitting military personnel and civilians for the purpose of studying and mastering psychological, chemical, biological, and nuclear warfare—all in contravention of the Nuremburg Code which was formulated by the Nuremberg court and pushed by the US on its allies after the Nuremburg Trials. Some of the details of these programs came to light at the 1975 Church Committee Hearings, others have since trickled out as documents have been declassified. These programs had far reaching effects on American culture, influencing counterculture figures (possibly including Charles Manson), spawning future terrorists (such as Unabomber Ted Kaczynski), and co-opting the media and entertainment industries to serve as propaganda arms for U.S. policy.5

Tensions resulting from some of these manipulations and suppressions boiled over in the violence and ferment of the late 1960s through early 1970s, but the disaffected groups were well-marginalized by the great social pressure provided by the ongoing Cold War.

The Cold War provided a uniting pretext for the American identity. We were the beacon of democracy in the world, a light unto the nations, a “city on a hill” as President Reagan famously put it.

Then, the Cold War ended.

Almost immediately, decades of simmering tensions and apocalyptic anxieties started coming to the surface. Political squabbles over issues such as abortion, local crime waves, gun control, drug policy, trade policy, civil liberties, the proper role of religion in public life, and the proper role of the Federal government stopped being fights-between-brothers who yet stood shoulder-to-shoulder against the greater threat from without; they instead became the basis for building feuding clans who, as time went on, had less and less common American identity and more and more smaller-scale tribal identities.

The early 1990s saw another protracted outbreak in political violence, from the Clinton administration’s war on the militia movement (resulting, among other things, in the massacre of the Branch Davidian doomsday cult in Waco, Texas and the murder of the Weaver family at Ruby Ridge, Idaho) to the bombing of the Oklahoma City Federal Building to the first bombing of the World Trade Center (among many others).

The country appeared to be unwinding so fast that in United States Trotskyist and Conservative Foreign Policy circles broad agreement developed which held that, one way or another, America needed a new enemy if it was to hold together long enough to shepherd the Free World out of the Post-Cold War Era and into a brighter future.

The result was a the formation of a new think tank called the Project for a New American Century and the issuance of its vision document, wherein a scenario was spun for bringing the developing world into the community of nations and establishing a new and even more robust American global hegemony and moral leadership. The program’s chief obstacle was American unity (or the current lack thereof).

However, the Project concluded, this could be achieved if a spectacular attack against the United States, amounting to a “new Pearl Harbor,” were to happen. In the view of the think tank, such an event was inevitable in light of the rise of political violence and terrorism around the world. The program directed foreign policy wonks to keep their powder dry and their draft legislation handy so as to seize such a moment, so they could rally the country to renewed greatness.

When the World Trade Center was attacked again, this time on September 11, 2001, the pre-loaded plans went into action. The PATRIOT act,6 cobbled together from failed bills from the 1990s (some of which were sponsored by then-Senator Joseph Biden) was quickly passed, establishing the surveillance state we now live under. Several other laws and expansions were then rapidly passed through during the Bush and Obama years, including the explicit legalization of Federal propaganda intended for American citizens, the removal of protections against Internet spying, the expansion of the ability to classify American citizens as “enemy combatants,” the expansion of circumstances under which American citizens lost their right to trial by jury and legal representation, and so on, and so forth.

Over this same period of time, the rhetoric around “protecting democracy,” which became the centerpiece of American state messaging under George W. Bush, soon began taking on a Cold War-like imperative to conform to the “mainstream” (lest one be labeled an “extremist” who might be subject to special scrutiny by the security services).

We were in a new war, a permanent Global War on Terror. It had many fronts—some of them in distant lands, some of them in the “hearts and minds” of the people here at home.

And, increasingly, discontent grew. 2009 saw the rise of Occupy Wall Street (which gave new life to the World War 2-born communist terrorist-activist group AntiFa) and the Tea Party movement (which started life as a string working class family-oriented Libertarian “Burning Man” type events, and then quickly morphed into a heavy duty Religious Conservative and Nativist movement that gave birth to many strains of the New Right that are detailed in Michael Malice’s book of the same name).

The government turned its eye towards controlling Internet speech, including through direct pressure on tech platforms, framing journalists for crimes, and jailing (or attempting to jail) leakers and whistle-blowers.

And, beginning on the fringes, the awareness grew that the entire edifice was being used as a massive international money laundering and influence peddling scheme, and that the Boomer-era leadership had become as corrupt, or more corrupt, than the Post-World War 2 establishment they had once opposed.

The result is a decades-long build-up of tensions that began erupting into persistent political violence that fits the pattern of historical run-ups to civil war.

Here are just a handful of hundreds of examples since 2016 alone:

June 18, 2016: Michael Steven Stanford grabs a weapon from a Las Vegas cop in order to assassinate presidential candidate Donald Trump.

June 14: 2017: Left-wing activist James Hodgkinson opens fire on a number of Republican lawmakers practicing for the annual Congressional Baseball Game in Alexandria, Virginia. Four people are hit, two more injured. Two people wind up in critical condition, but nobody is killed.

2014-2018 Black Bloc protests: Nationwide activity by AntiFa’s Black Bloc contingent targeting banks, Federal buildings, government employees, and the public. Numerous street battles erupt between Black Bloc footsoldiers and members of the Proud Boys, who themselves effectively morphed from a right wing social club into a community-action militia and then into a neo-fascist organization. Millions of dollars of property damage, numerous injuries, and a few deaths are recorded.

Summer 2020: The George Floyd Riots, co-ordinated nationwide by community organizers attached to Black Lives Matter and a few other left-wing activist organizations. Property damages total around two billion dollars, and at least 19 people are killed.

January 6, 2021: The US capitol is invaded during the electoral vote tallying ceremony by a mix of tourist-like protesters interested in supporting Trump and wannabe-radicals intent on everything from mischievous vandalism to scaring the Senate into throwing the election to Trump, despite the impossibility of this ambition.

June 8-July 1, 2020: Protesters establish the Capital Hill Autonomous Zone/Capitol Hill Occupied Protest in Seattle, Washington, erecting barricades and declaring secession from the United States. The occupiers enforce their borders with firearms while violence, arson, and rapes are reported from and/or leaked by video broadcast from inside the zone. Several non-affiliated residents are trapped inside. Several deaths are reported.

April 2, 2021: Noah Green, a Nation of Islam activist with mental problems, rams a barricade at the US capitol and kills several capitol police officers before he’s gunned down.

August 19, 2021: Floyd Ray Roseberry, a self-styled “Patriot” with numerous grievances against the government in general and the Democrat party in particular, drives a truck allegedly loaded with ANFO into the neighborhood of the US Supreme Court building and threatens to detonate it over a Facebook Live stream.

June 8, 2022: Nicholas Roske attempts to gain entry to the home of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh to assassinate him.

July 13, 2024: Candidate Trump is shot by a sniper at a campaign rally in Pennsylvania.

Once is happenstance.

Twice is coincidence.

Three times is enemy action.

This is not an anomaly. It is a trend.

The greater the slice of a population that feels as if they don’t have a say in what’s done to them, the more resentment and dissent foster violence.

This is the new normal.

And it is not a comprehensive list.

The Soporific Electorate

As all this has happened, the public at large has been asleep, reveling in soporific visions of political civility, social justice, and moral rightness. For thirty years, the children were nestled all snug in their beds. The long peace had thoroughly gone to their heads.

If you’re like around eighty percent of the American electorate, when you go to the ballot box, you’re voting for your values. This candidate supports your view on abortion, gay rights, minorities, social security, infrastructure-build out, welfare, pornography, education, tax rates, etc.

Secondarily, you select your preferred candidate based on personality. Who do you identify with? Who makes you feel comfortable? Who do you admire?

Unless you’re part of a relatively slim portion of the population, there is one thing you do not consider when you cast your vote at the ballot box:

Politics.

The business of politics has very little to do with any of the above.

Our confusion in this matter stems from the enforced (and I emphasize the “forced”) consensus view that the United States of America is a single entity (rather than a federation of entities) governed by a central Federal authority, with a single American way, a single American dream, and a single Foreign Policy Vision aimed towards uniting the world under its authority.

That central Federal authority is responsible for directing the lives of its subjects citizens and managing the economy so that everyone will ostensibly have a “fair shot,” and that nobody’s privilege will advantage them too much over others. We have all been taught to agree that this is how a good country is managed, and that our liberty (such as it is) depends on the proper administration of the economy and the culture by the State.

In other words, everything political has been taken off the table by the Total War State.

Politics is (and always has been) the business of exercising, apportioning, and restraining power.

In an American context, before the Total War State, politics was bloody.

It was violent.

And everyone knew it.

New taxes brought armed revolts as far back as the Whiskey Rebellion and the Shays’s Rebellion. The issue of “who controls the land, the water, and the minerals” animated wars in the American West between the cattlemen, the farmers, and the miners. The struggles over “what power do we allow the State to have over us?” dyed the soils of the United States red for a hundred and fifty years.7

“…the tree of Liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots & tyrants. It is its natural manure.”

—Thomas Jefferson.

That quote is on the walls of Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s plantation estate.

But you don’t often hear the whole context of the quote. It comes from a 1787 letter written to William Smith, the personal secretary (and future son-in-law) of John Adams, in which he discusses the Shays’s Rebellion—a garden-variety political dispute of the era:

“god forbid we should ever be twenty years without such a rebellion . . . the tree of Liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots & tyrants. it is its natural manure...[rather than the repression of inusrgents] the remedy is to set them right as to facts, pardon & pacify them.”

The goal of politics, in other words, is to use the power of the State to settle disputes. When disputes are not settled—because, for example, the political class is corrupt or derelict in its duty—political violence is the natural result.

Democracy comes in many forms. Our system was designed to be a constant tussle of disputation over who legitimately has the power to do anything—the individual, the family, the community, the City, the State, or the Federal Government? The legislature, or the courts? The President? Or nobody at all?

We don’t do that anymore.

“War is the continuation of politics by other means.”

—Carl von Clausewitz

“Politics is the continuation of war by other means.”

—Lazarus Long

A Total War State is incompatible, even in principle, with democratic governance. The best it can hope for is democratic legitimization. In such a situation where the ruling class still find elections obligatory, the members of the political class must find pretexts upon which to differentiate themselves from one another.

They cannot do so on political grounds. To disagree on whether the wartime state should have the power to regulate X part of life is to brand oneself treasonous by definition. The wartime state needs that power at its fingertips so that it may push public opinion this way and that, deputize the means of production for its aims, and direct the efforts of its citizens subjects.

So instead, we the people are induced to vote on who oughta get the shaft as we beg for crumbs from the political table:

“I oppose this war (because I’m not running it).”

“I think the government should be able to tell your neighbors how to run their families.”

“I think your business competitors should be forced to adopt the same risk strategy you have.”

“I think your countrymen should pay for your tuition, your retirement, and your medical care. You’re in need!”

All of them are variations of the basic promise:

“I feel your pain. I’ll make your life better…and your enemy’s life worse.”

These are the issues we vote on.

Because we have decided, broadly, as a people, that we do not like politics.

It’s too dirty.

And, oh my god, sometimes it’s violent!

The Competence Crisis

This kind of degradation of politics is de rigeur in imperial centers throughout history. When the imperial homeland is obligated to support imperial holdings, eventually the entirety of the homeland gets beggared to maintain the power of the empire on national security grounds.

It happened with the Bronze Age empires.

It happened with Rome.

It happened with France and Britain.

It happened with the Soviets.

It’s happened with us.

Whether its ambitions are ideological or financial or vanity-driven, empire is an expensive project, and all empires eventually go bankrupt as their treasure flows outwards to maintain their far-off holdings. Their currency inflates, then collapses, and eventually—either because they fall on their own, or because they are pushed while tottering—the empire collapses to become either a vassal state of a new empire, or a nation at war with itself.8

Maintaining such an empire requires vast armies of bureaucrats, and bureaucrats excel at diffusing responsibility. Any sufficiently mature bureaucratic system—be it a corporation or a government agency—is around 80-90% dead weight.9 This is why, for example, Elon Musk could radically downsize Twitter without crippling the platform in the long term.

Now look around you. Unless you are in an exceptional environment (they do exist, but they are, as the word implies, quite rare) then your workplace, the schools you went to, your church (if its membership is north of about 500 people), and your governments at all levels are all filled with the same 80-90% dead weight.

In any bureaucracy, the people devoted to the benefit of the bureaucracy itself always get in control and those dedicated to the goals that the bureaucracy is supposed to accomplish have less and less influence, and sometimes are eliminated entirely.

—Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy

When that situation continues long enough, weird shit starts to happen.

Air travel can, almost overnight, turn from the safest mode of travel in human history to an endeavor plagued regularly by equipment failures, mid-air explosions, door blow-outs, and (eventually) plane crashes.

Tech companies can start as nimble 20-person teams generating hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, only to evolve into astonishing conglomerates occupying whole skyscrapers while barely turning a profit.

The United States Military can go from a small operation that, less than a decade after a standing start in the middle of the Great Depression, took on the whole world and won, then morph into a world-wide logistics operation that can’t even figure out how to efficiently defeat a known enemy in open desert (Iraq) or successfully advise allies on how to beat back a technologically inferior force that’s so corrupt that its generals keep stealing the soldiers’ food (Ukraine).

The Secret Service of the United States, the savviest security force on the planet, can’t train its people effectively enough to secure an open-ground perimeter and control an obvious sniping position a mere 130 yards from a presidential candidate during an era of increased political violence.10

And the President of the United States himself, a regular practitioner of violence in all its forms (except perhaps the hands-on sort), the wielder of the greatest weapons arsenal in human history, can declare—and apparently believe—that violence and the United States have nothing to do with one another.

“There’s no place in America for this kind of violence or any violence for that matter. That’s not who we are.”

—Joe Biden, July 14, 2024

And this is a problem, because wars—including and especially civil wars—generally do not break out when the State is strong. They are started by the State when it senses that it is weakening.

It happened in Rome (both times).

It happened with Franco.

It happened with Lincoln.

And it is happening with us.

The Fate of the Fallen: Ignominy or Heroism?

Given recent events, and the catalog of recent political violence above, it is worth considering the historical significance of assassination as a tool of statecraft and revolution.

Let’s set aside disordered political violence (like the ideologically-motivated assassination of the head of DeutcheBank in 1989, the bombings of 1969, the activities of the Unabomber, the attacks on the World Trade Center, or the Capitol Hill Riots of January 6, 2021) and look at assassination’s use as a strategic tool to achieve the political objective of regime change or regime maintenance.

In terms of political strategy, assassination is a dangerous game. You always risk turning your target into a martyr, creating a situation where your target’s partisans become more of an obstacle to you than was the target himself.

When the Roman Senators assassinated Julius Caesar, they unleashed a civil war that wound up with Caesar’s nephew Octavian taking the throne and permanently gutting the power of the Senate.

“When you strike at the king, you must kill him.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

It’s always best to assassinate someone before they become a threat, or, failing that, to only pull the trigger when you’re confident that you can control the subsequent narrative and political succession. The US Foreign Service learned—or rather failed to learn—this one the hard way in the mid-20th century, as it knocked off one foreign leader after another and backed one revolutionary group after another, only to have the new regimes cause a lot more trouble than the old ones did. Examples include: The Ayatollah Khomeni in Iran, Fidel Castro in Cuba, Augusto Pinochet in Chile, and Saddam Hussein in Iraq, among many many others.

America, of course, is no stranger to assassination where Presidents and Presidential candidates are concerned.11

Ronald Reagan was shot by John Hinkley in 1981, because Hinkley had a sexual fixation with then-freshly-grown star Jodie Foster, who he knew disliked Reagan. If he killed Reagan, he thought, she might recognize him as a like-minded famous person and think he was hot. Reagan survived and thereafter played at taunting assassins when the occasion presented itself. His ability to bounce back from the assassination attempt and laugh at it helped him maintain his tough-guy image even as Alzheimer’s took his mind almost completely from him (by the end of his second term he was nearly as incompetent to hold office as Biden now seems to be).

John F. Kennedy was a middling President with some stand-out moments, but had he served his full term he would likely have not been remembered all that well. His drug addictions, his criminal connections, his womanizing, and his intemperate nature were all time bombs waiting to go off under his legacy, but he was instead murdered at the height of his popularity before he had a chance to make too many unpopular political decisions.

Kennedy died as a figurehead rather than as a man, and became the martyr for a generation. It is, as yet, unclear whether the person or people who accomplished his death got what they wanted out of the operation or not, but if the goal was to remove Kennedy as a factor in American politics, they did not succeed. His brothers and family were significant movers in the American political space for decades after his death, and his nephew is running for President today in a campaign that, though it won’t put him in the White House, could prove decisive in who next sits in the Oval office. If that’s his goal, he may well succeed.

Teddy Roosevelt, on a whistle-stop speaking tour in Wisconsin,12 was shot by a disgruntled saloon keeper. The bullet traveled through a metal eyeglass case and a folded-up 50-page copy of his speech, robbing it of its momentum. Roosevelt suffered a chest wound, but the bullet didn’t lodge deep enough to pierce any vital organs. He told reporters “I’m as healthy as a Bull Moose!” and carried on with his speech. The legend of this moment contributed in no small way to his political legacy.13

Now, here’s the thing: Roosevelt, despite having a number of admirable qualities, was a sonofabitch who didn’t take his duty to the Constitution particularly seriously. He, like his distant predecessor Lincoln, did quite a bit of work in re-making the Oval Office from an administrator’s command center into a throne room (work which continued long after his departure from office).14

Lincoln himself, despite the propaganda you’ve been fed about him, was neither a good man nor a particularly good President. He did not end slavery, nor did he wish to until the last few months of his life. He did not fight the war over slavery, but to “preserve the union” (after deliberately provoking the war by rejecting compromises that he’d previously pledged to find acceptable).15 His ultimate preferred solution to the slavery problem was not emancipation, but permanent exile for all the former slaves.16

Lincoln unilaterally suspended the civil rights of all Americans, and plotted to arrest the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court when the Court’s decisions annoyed him (but was dissuaded from this course of action and settled for merely defying the Court). He instituted illegal and unpopular conscriptions and expropriations, waged a total war on civilian populations, flouted the law whenever it suited him, and threw his political enemies in jail for the crime of speaking against him.17 He was an Hegelian ideologue (and pen-pal of Karl Marx) who believed that Washington D. C. should manage the morals and economy of the nation. He was, in short, everything that people feared Trump would be...

...but he was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth (an actor whose brother had virtually disowned him over the Civil War) in an act of personal revenge as part of a larger conspiracy to remove Lincoln and several other politicians in order to end the war (Booth struck four days late) so that another, more pragmatic politician might take his place and allow the then-normal contentious bargaining between the states to resume.

In executing his mission, Booth—as had the assassins of Julius Caesar before him—secured his target’s legacy as a hero and a martyr rather than as a tyrant whose actions led to the senseless death of nearly eight hundred thousand of his subjects (not including civilian deaths). For over a century and a half after, very few scholars have dared to scrutinize the ahistorical myth that grew up around Lincoln, despite the tissue of legends and lies that buttress his legacy being easily debunk-able with a cursory squint at Lincoln’s speeches and actions in their original context.18

But not all assassinations or assassination attempts provoke massive public support for the target. George Wallace was shot by an assassin while running in the 1972 Democrat Party presidential primary race—though he survived, his already-long shot campaign was mortally wounded.

Welcome to the Old World

Praise the Lord, and pass the ammunition

—Frank Loesser, 1942

Most of the time in the United States, assassinations are either the result of a disgruntled citizen wishing to render a “lead veto,”19 or the result of political figures using the resources at their disposal to remove obstacles or threats.

Such things happen frequently, because this is what politics has always been.

What is notable about the attempted assassination of candidate Trump isn’t that it happened, nor that Trump managed to escape only with a hole in his ear and some scratches on his face.

The most notable aspect is this:

Despite our regular contact with recent political violence through the media, despite the fact that we live in the global imperial hub that regularly rains violence down on other countries to advance our interests, and despite our entire national identity being wrapped up in the mythos of ordinary citizens starting a war against their government for the crime of seizing their weapons, Americans are shocked—SHOCKED—to find that violence is going on here.

There are four boxes of liberty.

The soap box, the ballot box, the jury box, and the ammo box.

Use in that order.

—19th century American Proverb

Our forefathers and foremothers were often upset when someone took a shot at a President or a candidate, or when corporations or gangs started wars with one another or tried to cow the common people into compliance, but they were not surprised. They knew, as did all the generations before them, that violence is not just a tool of politics; politics is, and always has been, the art of achieving goals through the strategic use of violence.

In other words, politics is mostly peaceful.

In a country where Presidents routinely boast about having kill lists, publicly claim credit for assassinating the leadership class members of countries with whom we are not at war, where coordinated riots have been used to sway a recent presidential election, and where another less-coordinated riot attempted to reverse that same election, we have no right to pretend—as our sitting President did on July 14 of this year—that political violence, or “violence of any kind” has “no place” in America.

Because it clearly does. And it always has.

And now, thanks to the confluence of the end of Empire, the growing global crisis, two decades of constant preparation and training by paramilitary activist groups at both ends of the political spectrum, and thirty years of relentless messaging about the illegitimacy of our electoral system by both major parties (when they lose) right alongside loud crowing about the absolute integrity of our electoral systems and institutions by both major parties (when they win), a season of violence is upon us again.

We. Are. Due.

Times like this call for maturity, not idealism.

A significant portion—perhaps the majority—of the American population feels ill-served and hard-done-by. It is easy to look at one’s neighbor and mock their grievances because their grievances seem invented, or of-their-own-making (and, let’s face it, quite often they are…as are our own).

But it is also worth remembering that they, like you, are living in the fading light of an increasingly desperate Total War State, subjected at every turn to a non-functional bureaucracy, beggared by an inflating currency (while over half of those increasingly-worthless funds, in total, are taken in taxes), and that many of them have been lied to and conned into taking on debt loads that will ultimately prove as unbearable as the Federal Government’s own staggering debt.

The problem might not just be that they are irresponsible.

It may be, instead (or also, if you prefer), that the entire system is so corrupt that responsibility is nearly impossible—and that those who do manage to be responsible often get screwed over anyway.

Situations like this recur from time to time in history.

Situations like this are why political violence exists.

Violence is the ultimate nature of politics.

The unpleasantness of violence is the reason why politics—real politics—is a discipline worth resurrecting.

What powers need to be reapportioned?

What powers need to be de-consolidated, devolved, and/or recanted?

What departments need to be disbanded?

And who will be thrown out of work as a result?

This is a fight everyone will eventually have to join, whether they want to or not. I have been watching the dreadful approach of this historical moment for a long time. I am not happy about its arrival.

Yet, here we are.

And as long as the public continues to react to unrest and political violence with a sense of affronted self-righteousness, the public is not behaving in an adult manner. In a democracy, that’s a problem.

Children are no more fit to rule than a cowardly king who shouts for all to hear:

“Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?”

Support My Writing

Drawing on my background as a novelist, filmmaker, audiobook producer, and FX artist, my life-long study of history and psychology, as well as my thirty-years-plus experience in fringe communities, I publish articles a couple times a week on history, art, geopolitics, and maker stuff (blacksmithing, carpentry, etc.) You can find one (or many) of each sort by hitting the links on each of those four terms. This column is a non-trivial part of how I make my living, and my supporters literally saved my life earlier this year.

When not writing articles for Substack, I write novels and how-to books, host a podcast about writing and creativity, and spend the rest of my time blacksmithing, fixing things, and walking in the forest. You can find everything else that I do apart from this substack at http://www.jdsawyer.net

Primary reports of the exact words vary, but this is the version which is most frequently remembered.

Banana Republics are so-called because the United States sponsored a series of revolutions in South America which set up puppet dictatorships. The first was conducted on behalf of the United Fruit Company to ensure a reliable supply of Chiquita-brand Bananas on American supermarket shelves.

As detailed in chapters 2 and 3 of my book Throwing Lead

For a fantastic article on the entire development of this flavor of bullshit, check out the Dr. Rollergator classic on Stochastic Terrorism.

For further reading, a good start is Tom O’Neil’s book Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties. See also Kirby Dick’s documentary This Film is Not Yet Rated for a quickie introduction to the relationship between Hollywood and the National Security establishment. The rabbit hole after this point goes very deep indeed.

Which, among other things, basically undid all of the reforms to the US National Security infrastructure instituted after the 1975 Church Committee hearings revealed CIA and FBI malfeasance in the 1950s-1970s

I have deliberately left the Indian Wars and the treatment of native Americans aside in this article, both because the subject is too large and because, until the twentieth century, the native American populations were considered conquered peoples rather than citizens. The dynamics of conquest are not the same as the dynamics of internal political violence.

For more on this dynamic, see Arnold Toynbee’s A Study of History

This is the bureaucratic manifestation of the Pareto principle, which seems to be a basic law of the universe, and is well-attested in management studies going back at least to the early 1980s.

Either that or the organization’s general competence has degraded to such a point where those that wish to use such an excuse as a cover for more nefarious activities can plausibly do so.

Literally, a campaign tour where a train would stop on the tracks in the middle of a town, blow its whistle, and the locals would assemble to hear a speech from the caboose.

I had initially talked about electoral victory here, but a weather-eyed reader pointed out that I was conflating two separate Roosevelt events: His Presidential victory, and his failed Bull Moose Party run (where the assassination attempt happened), which nonetheless did quite a bit to foster and shape the Progressive movement that he championed.

See Edmond Morris’s three-volume biography of Roosevelt’s life—particularly the final two volumes—for a full account of this aspect of Teddy’s life.

A commenter took serious issue with this characterization, as it gives too much credence to Confederate historians’ read of the situation. Our philosophies of historical inquiry are at odds—in my view, it is the business of historians to look at the way things are rather than to build narratives with the aim of justifying one or another moral/political program. One cannot understand the events leading up to the civil war if one assumes that the “bad guys” were always lying about everything, or that the “good guys” don’t.

Lincoln DID decline to to take actions that might have saved the union before war was necessary and DID prevaricate and thus sew distrust with regards to his own views on abolition as well as in matters related to compromises to keep the South in the union, which amounted to provocation in that climate. He did this for reasons of political survival—his party being composed of a powerful minority of radicals, whom he didn’t want to piss off. You can support Lincoln’s actions, and reasonably conclude (as did the commenter) that playing around with compromises would only delay the inevitable war—it’s a plausible read. My goal in to demonstrate how the myths surrounding Lincoln are at odds with an understanding of how his assassination affected the American political system contrary to the goals of the men who conspired to kill him. Therefore, I invite you to check out the shenanigans surrounding the following historical events: The Crittenden Compromise, the Corwin Amendment (which Lincoln claimed not to have seen after being involved in its passage and possibly in its drafting), and the Article 5 convention proposed by several major figures of the time. See also this audio-lecture summary of the matter (from a Confederate-sympathetic point of view).

This footnote erroneously attributed Liberia to Lincoln’s vision on this point. In fact, Liberia was was a pre-existing phenomenon, established in the early 19th century by free former slaves who had emigrated from the United States. Lincoln and other African re-patriationists latched on to it as a solution to the problem of what to do with a bunch of freed slaves, but the project failed early and support for it collapsed as the Civil War dragged on. Hat tip to Herbert Nowell for the correction.

Including, ironically, John Wilkes Booth, who later assassinated him.

Yes, you can still be VERY happy that limitations were placed on legal slavery in America following Lincoln’s death without lying about who Lincoln was, what his aims were, or what he did.

Wait, what? Limitations? Wasn’t slavery abolished?

Nope. Check out the 13th amendment, ratified in December of 1865 (Lincoln was killed on April 14 of that year, a week after it was passed out of the Senate). It still permits the enslavement of the incarcerated, and it does nothing to limit politicians’ right to kidnap young men and marching them into gunfire against their will to achieve a political goal—i.e. “the draft.”

An assassination of a political figure by a member of the public in retaliation for disliked policy actions.

A great piece, Daniel.

So, lots of thoughts.

1. I don't find this shocking. I am more shocked at how little this is thought in general, but then again I remember some of the continuation of the Days of Rage in the 70s and early 80s (I consider the 81 Brinks robbery the last gasp of 60s radicalism) yet they have been effectively memory holed and several principals rehabilitated into legitimate political actors to the point of helping select a POTUS candidate.

2. I think you are too rough on Lincoln but that you are not alone. I think we are in the part of the historical cycle where in overcoming the heroic narrative historians still don't see him as a real person, but as the villain image of the hero. And I say that as someone who considers his actions the third most important in creating the ability for the post WW2 world you describe.

3. Speaking of Lincoln, he was 7 when Liberia was founded. It declared independence from the US in 1847 although the US didn't recognize it until 1862 under Lincoln. Certainly something similar was what he supported, and in retrospect he might have been right, but he was not directly involved in its creation.

4. I'd put the date of sustained illegitimacy of Presidential elections at 2000, not 1992. While I do understand and heard the claims of illegitimacy you reference relative to Clinton I also heard those about Kennedy who was dead before I was born and about Nixon and Reagan's re-election.

What I didn't hear, and what Nixon specifically rejected in 1960, was the candidate himself engaging in that publicly. It was Gore who broke that taboo and I think that is critical. Once Gore did "polite society" allowed such beliefs became an acceptable thing to act upon. There is a much stronger line between his lawsuits and January 6 than anything said about Clinton or Nixon or Kennedy.

Once people who wield the power "awarded" in our elections decide bare-knuckle fighting in public is allowed the genie is out in a way all the post 60s violence never achieved.

5. My only surprise about last Saturday was we made it this far.

6. I think a very important extension of why it is worse now, as you admit around directly affecting high level elections (as opposed to things like The Battle of Athens) is the increasing centralization of power. While you allude to this I'd say Shelby Foote's "the United States are" vs. "the United States is" (harkening the problem all the way back to Lincoln) is the less relevant lower levels of power are and the less relevant certain states are (see the California exemption under the Clean Air Act allowing Sacramento to effective set air pollution policy nationwide) the more all the stakes are on that one bet, the President.

The irony is, as you showed on your Chevron post, the one institution pushing back on that "all the stakes" thinking, the SCUS, had made itself the single biggest stake and restoring it to that position is the goal of at least half the current factions (and not just on the Left).