Please note: This is a long post with many footnotes and pictures. It may get cut short by your email service (especially if you’re on gmail). If you have this problem, you may read the full article in your Substack client, or at http://jdanielsawyer.substack.com

The Culture that Made Us

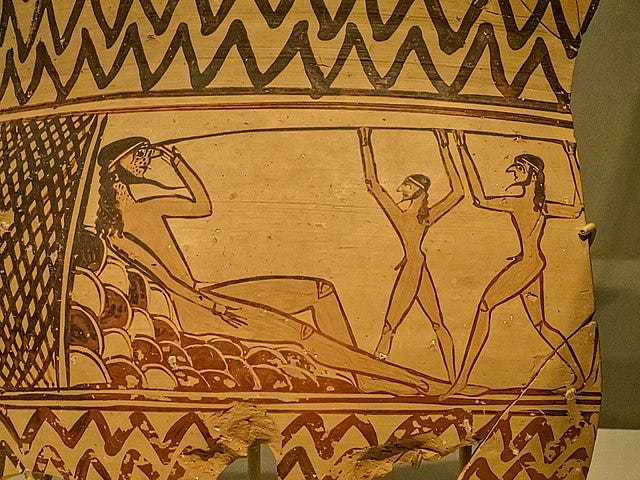

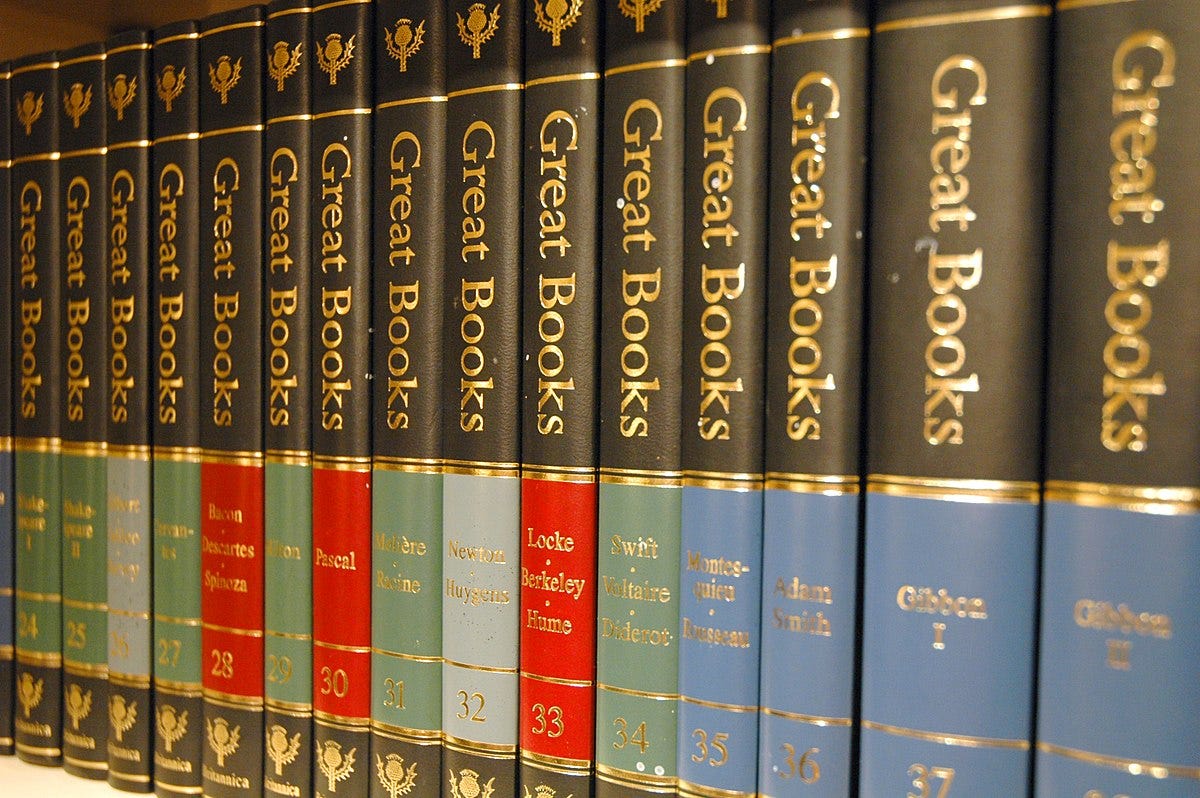

The English branch of Western culture is built, ultimately, upon a rather strange foundation consisting of a mere handful of mythic canons: The Illiad, The Odyssey, The Bible, and the works of Shakespeare. This small bibliography doesn’t constitute our entire heritage, but these are the canons that persist through age after fertile age. When all that survives of ancient philosophy and science were lost to the west, we still had the stories derived from the first three. The language we speak—both the words and metaphors—has been profoundly shaped by these literary works.

Which is a bit…odd, when you think about it.

Two of them are the literary lifeblood of the Hellenic world. One of them is the scriptural canon of a small Levantine culture that sat at the crossroads of the ancient world and spent most of its time being subjugated by one or another major empire. One of them is a collection of plays from a single author from the English Renaissance—one single author (out of many greats of the time) who didn’t write works to be read, but to be performed.

Why were these works preserved and prized above all others?

Perhaps it is they have something in common that is, on the face of it, pretty upsetting:

They are, in senses both petty and grand, anti-moral.

Stings In the Cultural Tail

First, the petty:

Stripped of their venerated status, none of these works are what most people would consider “suitable for children.” None of them could possibly be honestly adapted to the screen in an un-redacted form without earning them the kind of rating that would get them blacklisted from cinemas (and some of the incidents they contain wouldn’t be legal to stage or film at all).

They are, after all, filled to the brim with gore, incest, seduction, human sacrifice, bestiality, prostitution, witchcraft, child abuse, rape, and especially blasphemy; blasphemies against the religions they underlie and/or emerged from, and blasphemies against the sacred totems of every era they’ve ever traveled through. Even with their venerated status, all of them have been banned, censored, and criticized endlessly over the centuries for their “problematic” content.

But something grander, too, is at work:

Every one of them is subversive—i.e. they are intended, in whole or in part, to tear down a sacred tenet of their mother civilization and erect, in its place, a new way of looking at the world.

The Iliad is heavily critical of the war and the warriors who were sacred totems in ancient Greece.

The Odyssey prizes the guile, independence, deceit, and hubris1 of a lone man who triumphs against the will of the gods who seek to punish him.

The Bible haltingly replaces the ancient polytheistic Levantine religion with a henotheistic2 one, and then a monotheistic one.

Once you reach the New Testament, it gets even worse, as the Gospel tales subvert both the ancient Hebrew and the Hellenic visions of heroism, morality, ethnic solidarity, and sacrifice and replaces them with a new vision that is almost antithetical to those which went before—a move which was condemned at the time by both Jews and Romans as “atheistic” and “immoral.”3

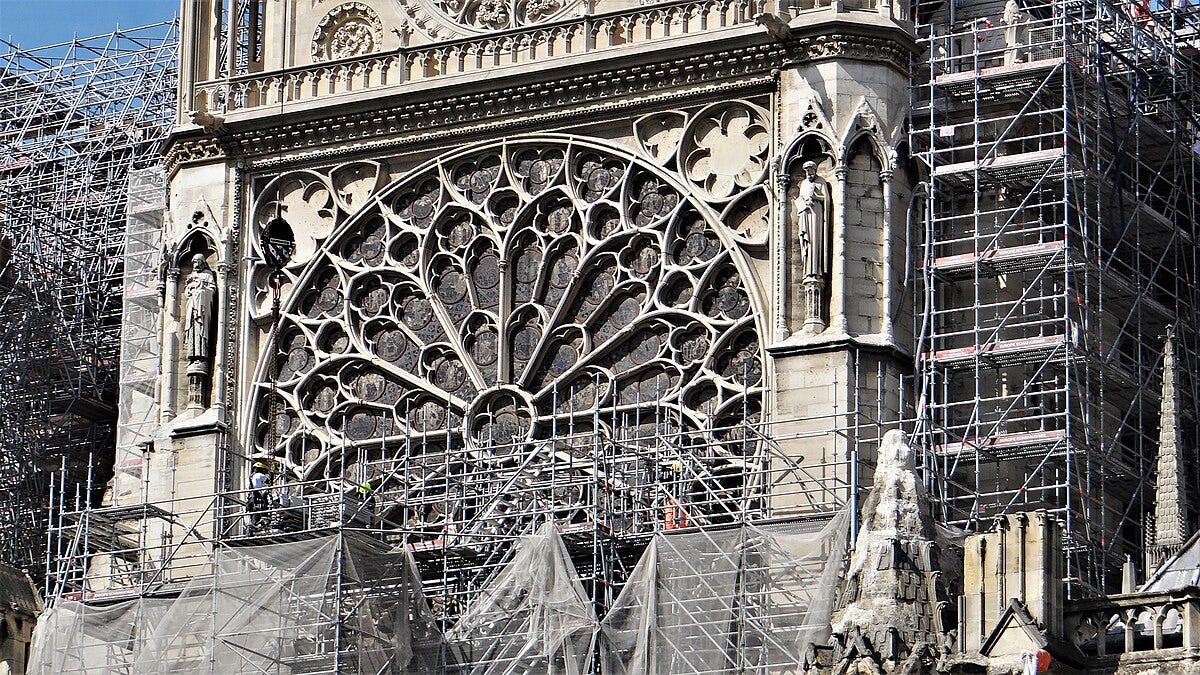

The works of Shakespeare came at a time of cultural rebirth at the tail end of some of history’s bloodiest religious persecutions (carried out by the Tudor sisters Bloody Mary and Elizabeth I, each of whom targeted the opposite faction as the other) which came in turn upon the heels of the bloodiest series of dynastic wars in English history. Shakespeare’s plays take shots at Christian morality, gender roles, sacred totems of English history, and subtly-but-persistently propose a new synthesis of Celtic paganism, Classicism, Platonism, Christianity, English folk mysticism, and modernism which came to define the English worldview (and was revisionistically called “Christian” by later generations).

Western culture, in other words, is based on subversion. Its vigorous tradition of subversion and counter-suvbversion is what has kept it fresh and vital for the past three thousand years. With all due respect to my friends in the “superversive” literature movement, subversion is the essential building block of the culture they wish to rebuild, and abandoning it because it seems to have spun out of control is the same sort of reasoning as that displayed by a man who castrates himself in order to control his sexual desire.

Such an impulse may be understandable in desperate straits, but it fundamentally misunderstands the nature of healthy function, and invariably winds up swapping out one disease for another. It’s of a piece with the impulse to tear down statues of historical figures who are now deemed villainous, as it springs from the same, very shallow, understanding of morality:

That “virtues” and “vices” are distinct forces in the human character.

Of Vice and Virtue

If you read my article (In)Sensitivity Readers,4 you will have seen me touch on this concept, but for those of you who missed it, here’s the quick and dirty:

“Moral” behavior is much more complicated than “controlling bad impulses” and “cultivating good impulses.” In fact, if you consider a list of those things you find most virtuous, and a companion list of those things you find most vicious, you might come up with something like the below:

Virtues Vices

Fortitude | Stubbornness

Constancy | Stagnation

Courage | Arrogance

Survival | Greed

Ambition | The appetite for arbitrary power

Honesty | Cruelty

Tolerance | Self-righteousness

Temperance | Puritanism

Love | Hatred

Loyalty | Tribalism

Justice | Vengeance

Loving joy & beauty | Decadence

Ingenuity | Recklessness

Forgiveness | Self-vicitimization

Discernment | Judgmentalism

Mercy | Enablement

Humility | Weakness

Adaptability | Equivocation

Notice how, in the two columns above, the “vices” are merely unchecked and/or situationally inappropriate versions of the accompanying virtue. The cultivation of a virtue such as “humility” will check a virtue such as “ambition” and prevent it from exploding into the vice of “seeking arbitrary power.” But if a person were to cultivate “humility” while abandoning the virtue of “courage”, you wouldn’t get a humble individual of good character, you’d get a self-effacing coward.

Morality is complicated, and it has very little to do with “stimuli” and “provocation” devoid of context. Instead, moment-to-moment moral conduct is a surface layer floating atop a vast and deep tradition which provides context for the human experience. That tradition is what we call “culture.”

Culture is a funny thing—when we’re in a healthy one, we enjoy it, but we don’t always notice it. Health in general is often that way. But when culture is unhealthy, or even dying, we are prone to casting about any-which-way to fill the void left by its ebb.

And if you want to build (or rebuild) culture, especially Western culture, you need a peculiar species of human to lead the way.

The Best of the Best?

I walk this empty street on the boulevard of broken dreams.

—Green Day

The above is the opening line of the second stanza Boulevard of Broken Dreams a 2004 hit single from Green Day’s seventh studio album. By the time that album was released, lead singer Billie Joe Armstrong was thirty-two years old, and he’d been performing for around seventeen years. Only a man with nearly two decades in the arts business could have written the song, and such men and women are very rare indeed.

In the 1980s, Armstrong was just another kid with a punk band. He grew up not far from where I did, and his career incubated in the shadows of the communities and locations that I write about in my Clarke Lantham Mysteries series. I never met Armstrong—he was older than the crowd I ran with—but I knew hundreds of people who wanted his job. I also knew people scrambling in local radio, news, activism, film, television, fiction writing, and tech. Some of them are people whose names you know, but most of them are not. And that’s no accident.

These are brutal businesses, and they always have been. You don’t just have to get lucky to make good, you have to be within the top 10% of your discipline to even have a chance at getting lucky. Want to have your books read in 100 years? Want people playing your music at their weddings? Or watching your movies? Or reciting your poems and stories around their campfire? Do you want people on the Moon or on Mars using your imagery, words, and sounds to help them imagine what Earth is really like? Then you’d better be the best in the world at what you do...and then pray like hell that you get lucky.

Lucky?

Well, the things you’re interested in writing, painting, singing, or playing about have to be things audiences are hungry for. That means you have to know the languages they speak, the desires they hold secret, the fears they harbor, and you have to communicate to them in a way that resonates.

We’re all familiar with the phenomenon of the artist who tragically struggled during life only to become a phenomenon during death—such artists, including such luminaries as Van Gogh and H.P. Lovecraft—were literally before their time. The value they had to offer was unintelligible to their contemporaries, and only became obvious as time washed away the tastes-of-the-moment and the then-popular artists with them, leaving such figures to sparkle like gold dust in a pan.

Everyone wants to be popular—that’s the primary attraction of the arts. But the spectacular difficulty in being good at what you do (to say nothing of the element of luck), washes away the vast majority of aspirants. The failures you see in public are the top 20-30% of people who made a go of it. The people you’ve actually heard of who weren’t just one-hit wonders—including those who struggle to make rent—are in the top 10% (or less).

The same is true in politics and philosophy.

With all of that in mind, consider:

What kind of person produces art that is good enough and lucky enough to be remembered, generation after generation?

These are the people who create culture, so it behooves us to find the answer.

We can start by looking at the luminaries of the past. When we do, we find something curious:

They are all—every last one—wounded, deviant, and, by any reasonable measure, insane.

A Short List of Cultural Luminaries

Every one of them?

Yes, every one.

Consider for a moment that the only people who have the wherewithal to create what eventually becomes culture are incredibly driven to do the impossible. Those who last long enough to make a dent can’t not create. You have to have a real burr up your ass about something in order to spend your life fiddling with ideas, shouting into the void, and enduring the hardship involved in making art that resonates.

You also have to have a serious deviant streak to live the kind of life, to amass the kind of life experience, and to become saturated in the kinds of ideas that allow you to weave the dream in a way that others can enter it.

No matter where you look, you find that those who are influential are undeniably weirdos along at least one axis.

Ghandi was an ascetic who believed in the spiritual power of semen retention, and made a habit of sleeping naked with his young nieces in order to stimulate the production of semen for which he could then deny himself release. That’s right; he believed that blue balls were spiritually empowering, so went out of the way to get them.

Hegel, Schopenhauer, Plato, and Heidegger were occultists, and saying that barely scratches the surface of how truly and fantastically twisted each of these fellows were.

Lord Byron was an itinerant warrior, a drug enthusiast, a bisexual, a swinger, emotionally unstable and destabilizing, and a scandal to all that knew him.

Bram Stoker was involved in a love triangle with Oscar Wilde, was probably bisexual, and drew inspiration for the character of Dracula from his own financially ruinous addiction to the company of ladies (and possibly gentlemen) of the night.

Jack Parsons—the founder of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab and of the Aerojet Corporation—was a Thelemic priest (the pagan left-hand path pioneered by the infamous Aleister Crowley). L. Ron Hubbard (the 20th century’s most prolific science fiction author and the founder of Scientology) and Robert A. Heinlein (author of Starship Troopers and Stranger in a Strange Land), were both, for a time, part of his esoteric coven.

C.S. Lewis was a devotee of sadomasochism who very much enjoyed whipping his female companions and leaving stripes on them—he even signed his letters to an intimate male friend with the playful kink name “Philomastix” (literally: “Lover of the lash”).

J.R.R. Tolkien had a deep and abiding interest in paganism and sought to synthesize it, at least through his art, with Catholicism. He was also a glory hound, an emotionally abusive husband, a skinny-dipping aficionado, and a practitioner of a Victorian form of filial bonding that is best characterized as “romantic friendship,” a tradition whereby men who were not sexually involved with one another formed the kinds of intense emotional bonds that we today associate exclusively with romantic relationships (i.e. characterized by high-pitched devotion, protestations of affection, and intense jealousy). He was a complicated character, and Michaela McKuen recently wrote an excellent article covering some of Tolkien’s more interesting difficult points:

Mozart was a drunk, a cad, an occultist, and a dirty-minded aficionado of scatological humor and scatological sexuality.

Hemingway was a drunk, a womanizer, a soldier-of-fortune, and a bisexual (at least situationally).

Shakespeare and Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were all notorious womanizers (among other interesting deviant tendencies).

Alexander the Great was probably gay, and Aristotle, his tutor, spoke in favor of the wisdom of pederasty as social policy (though he indicated he had more complex thoughts on the subject which were not, alas, preserved).5

Wordsworth and Coleridge were both morphine addicts.

Philip K. Dick was a schizophrenic drug fiend, an occultist, and a very strange flavor of Christian mystic.

William Golding was a pederast.

Aldous Huxley was a drug fiend and, for a time, a Fabian.

George Orwell was a socialist who enlisted in a foreign country’s civil war in order to advance his ideology.

Nietzsche was committed to an insane asylum at the end of his life, and was involved for many years in something approximating a very toxic group marriage.

Theologian Karl Barth was involved in a group marriage with his live-in protege and his wife.

Reformer Martin Luther persuaded a nun to break her vows and marry him in violation of his own vows. She also brought her sisters into the home, and by some accounts they were also involved with Luther. Luther also wrote enthusiastically antisemetic screeds, and talked in his journals about his struggles with demons and his love of farting on Satan’s face.

Leonard Cohen had many adventures with drugs and sex and religion which served as the pith of his art.

Mary Shelley had sex on her mother’s grave.

Lincoln was a monomaniacal bastard with a seriously sadistic streak running through his personality.

Martin Luther King was a womanizer and not above playing the grift.

O. Henry was a felon embezzler who abandoned his wife to live on the lam, only to return and face trial when she was dying. He wrote some of his greatest stories in prison.

Charles Dickens abused his wife and had a thing for teenaged girls.

George Eliot (pen name of Mary Anne Evans) was the common-law wife of a married man whom she eventually left for one of her other lovers before finally moving on to another lover with whom she eventually had children.

Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women, was a transcendentalist, a sensationalist and pornographer (of the written variety, by the standards of the time), and a lesbian (though it is not clear that she ever had significant sexual relationships with anyone).

Francis of Assisi was a madman who preached the gospel to forest animals.

Dorothy Sayers was a free-love activist.

Horatio Alger was a self-loathing homosexual.

Roald Dahl and Ian Fleming were dissolute abusive womanizing party animals filled with resentment and rage.

Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael were all gay (and Raphael appeared to have had a particular taste for pubescent boys).

Napoleon was, well, Napoleon.

And let’s not even get into what The Bible record about its heroes,6 from Samson to David to Solomon to Moses to the Patriarchs, and just about everyone else.

I could go on almost forever.

These are the kinds of people who create culture and move history. This is how it has always been, because this is the only way it can ever be—because it is only people who walk through the borderlands who acquire both the experience and have the drive to move the levers of culture and history.

The Truth Shall Set You Free?

Depending on where you sit on matters of religion, philosophy, and politics, some of the above characters may be people you’d rather hadn’t lived at all. On the other hand, some of them are certainly ones who made contributions you deem vital to your heritage. In their personal lives, some of these people were more “good” and some were more “evil,” but all (or nearly all) were—like all of us—a mix of the two.

But make no mistake: there is no name on the above list that is dispensable to your culture. Erase any one of them and the world you know doesn’t just change, it falls apart. Every single one served as the inspiration for thousands—if not millions—who came after them. Every single one shaped the deep, spiritual conversation that comprises our culture. Every one spawned artistic, philosophical, technological, and political legacies that built the mightiest7 civilization in the history of the world (the one that so many now fear is declining).

If you feel as if that list reads more like an indictment than a catalog of luminaries, that’s not an accident. It is an indictment, but it’s not an indictment of the historical figures described.

It is instead an indictment of the shallow, posturing moralism that those who most loudly champion the power of culture—the Wokists on one side, and the Conservatives on the other—pretend applies, or should apply, to art.

“Art” includes, by the way, the scriptures and mythologies underlying the world’s great religions, which are routinely subject to censorship campaigns (and have been for hundreds of years).

What we are taught to regard as “morality”—the bundle of expectations and codes of conduct to which we are tacitly bound to by our cultures and subcultures—is useful for living a peaceful and dignified life, but it has almost nothing to do with culture.

The very idea of culture as a “moral” enterprise (at least in this sense) is a recent one indeed, dating back only as far as the Reformation, when Protestant sects began to distinguish themselves from one another with the varieties of asceticism they chose to champion. This moralistic conception of culture is seeing a resurgence right now, as both the Woke Left and the Christian Right try to flay the decaying flesh from the bones of Western civilization.

Each side claims that the culture is dying because the sins they regard as cardinal are now in ascendance.

For the Woke and their allies, racism (and other oppressive attitudes) is the ultimate sin, and since at least 2010 the attitudes abhorred by the Woke have come roaring back from a long period of quietude.8

For the Christian Right (and their fellow travelers) the enemy is “hedonism,” especially in the forms of promiscuity, gender bending, abortion, and homosexuality, all of which have become much more publicly visible than they were before the 1960s.9

But racism and oppression can’t kill a culture—every culture in history has been racist and oppressive to a greater or lesser degree.

“Hedonism” can’t kill a culture either. You might have noticed that the list above is replete with people (including the Christian luminaries on the list) who spent a non-trivial portion of their lives devoted to activities that the Christian Right would castigate as “hedonism,” and yet these are the people to whom we owe our culture’s very existence.

Yes, racism and injustice spun out of control can spur a people to actions that prompt their own destruction.

And yes, a certain flavor of hedonism emerges during cultural nadirs. But this flavor, with which we are now surrounded, is not a culture-killer; it is a symptom of decay. When a cultural tradition loses continuity, chaos erupts because people are trying to find their way without firm cultural grounding. In so doing, normies stray into the borderlands where, traditionally, only the madmen dwell.10

What can kill a culture, though, is failing to pass it on. This project is something that both the Woke (and their intellectual ancestors) and the Christian Right (and their intellectual ancestors) have conspired together on for nearly the last two centuries.

Left wingers call their end of this conspiracy “progress.” Right-wingers call their end “renewal.” But in both cases, the project is the same: To carefully edit history so it will conform to a Utopian moral vision. The essential difference between the left and the right is that the left pursues an impossible future, and the right seeks to re-capture an illusory past.

One thing both camps agree on is that important pillars of the culture should not be transmitted. Edit the art and thought of the past, ban the offensive books and censor the important artworks to create the illusion that their preferred moral sensibilities have always obtained. Eliminate the wrong ideas and heroes, and reinforce the right ones, and you can make the world into what you want it to be.

In other words, both camps see art as valuable exactly insofar as it makes for useful propaganda.

The Lie at the Heart of the Culture War

In both cases, the base camps of the biggest culture war factions do not value art or artists, and it shows in the art they produce.

Neither the Woke nor the Conservatives produce good art anymore—indeed, most of what we now look back on as “great art” from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was deemed scandalous and derided by those-who-know-best at the time of its release.

Books like The Lord of the Rings, literary innovations such as novels (not to mention genres such as romance, crime fiction, science fiction, and horror), musical forms such as jazz and blues and rock’n’roll (and all their children), theater forms accessible to the masses, stand-up comedy, movies and comic books per se, impressionistic painting (and the invention of photography that made the impressionist revolution necessary)—all of these were derided as “immoral,” “corrupting,” and “a danger to public order.”11

And, of course, these criticisms were all correct.

Art’s function is antithetical to moralistic concerns, because it opens the consciousness of the audience to experiences that are out-of-bounds, either morally or practically. It holds up a mirror to the audience, allowing them to explore their own anarchic desires and fears, to experience spirituality in ways that can’t easily be done under the careful guidance of priests and theologians, and to discover the parts of themselves that do not fit with the world they live in. And this function is vital, because civilization itself is an act of compromise between the warring parts of our natures. Nobody ever fits it entirely, especially in a technological civilization built around bureaucrats and the machines that they manage.

Now, that’s all as may be, but if you are an ordinary human, you’re likely to look up at that list of sinners and say to yourself:

“Well, some sins are worse than others. At least my heroes weren’t atheists/faggots/racists/slaveholders/misogynists/whores/abusers/etc.”

And, to give you your due, maybe your heroes didn’t practice the vices you find most abhorrent. That doesn’t change the fact that in their own time, they were madmen, and deviants, and what most decent ordinary humans would call “horrible people” at one point or another in their lives. It also doesn’t change the fact that it was their alienation from the world in which they lived, and their deviance from it, that gave these luminaries the tools and motivation to build the culture you depend on, the culture you want back, or the culture you want to rebuild.

What Makes a Culture?

Now that you know a bit more about what some of your idols were like, it may be worth considering why you idolize them.

In every case, I daresay that the reason is exactly one word long:

Vision.

As Georgia Bruce so brilliantly pointed out in her recent column Inside a Tart’s Handbag, what all these deviants give their audience is the power to see themselves, and to see the world, usually in ways that are not permitted outside of the artistic dream-state.

Consider the ending of Blade Runner.

Villain Roy Batty, shown throughout the film to be a sadist and a murderer, chases the film’s hero to ground and then, when victory is in his grasp, opts not to end the hero’s life, but to save it. After expending his last effort, he sits down as the expiration of his artificial life overtakes him. As he takes his last quiet breaths, he looks at the hero and utters what has become on of the most famous monologues in film history:

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-Beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate. All these moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.”

And with that, the villain becomes the prophet. His vision, hard won from his journeys through the dark, changes the life of his enemy, leaving both of them better able to embrace virtue and find the peace they desperately sought.

“Artist” is the word that our culture gives to the prophets, the shaman, and the madmen who wrestle with the dangers of the outer world, and the inner, and bring meaning to their own lives by distilling their visions into a form that their fellows can digest.

Conservatives, the Woke, and the Creation of Culture

For the normal person with normal concerns, who wishes only to live a healthy and uneventful life, the shamanic visionaries we call “artists” represent a problem, because, regardless of how uncongenial their work, they’re telling you the truth.

Lena Dunham painted a tragic vision of the Millennial hook-up culture in Girls because she lived it.

The glorious indie films of 1990s queer cinema—like Better than Chocolate, or Jeffrey, or Tales of the City—paint pictures that both cultural liberals and cultural conservatives can be moved by because they tell the truth about the gay experience of the eras they depict, in turn because they were written by people who lived them.

The same can be said of Larry Clark’s Kids, Kevin Smith’s Clerks, and Mike Judge’s Office Space, all of which hail from the same era and are written by men who lived in the worlds depicted.

Such strange vision and experience is also essential to the horrific and disturbing films of Lars von Trier (Nymphomaniac, Antichrist, Dogtown), the tragic erotic visions of Gaspar Noe (Love, Irreversible, Enter the Void), the intellectual brutality of Stanley Kubrick (The Shining, Dr. Strangelove, A Clockwork Orange), the dark ruthlessness of David Fincher (Fight Club, Se7en, Gone Girl), and the complex beauty in the films of Milos Forman (Ragtime, Amadeus) and Darren Aronofsky (The Fountain, Black Swan).

Audiences can argue about whether what these films (and other artworks like them in whatever medium) depict is desirable or depraved, and to what extent—that is, after all, part of the audience’s job.

But what audiences can’t argue about is whether they have been shown something true—the integrity of the work in each case is of such a caliber as to brook no honest dispute.

When you hear people (like filmmaker Cody Clarke, or me) say something to the effect that “that there are no conservative artists,” this is what we mean.

And as for the rising tide of voices on the cultural Right (like former Trump staffer Joshua Steinman, or the people cataloged here by conservative commentator Brian Niemieir, ) who are complaining loudly that establishment conservatives won’t fund art and always lose culture wars, they are beginning to dance maddeningly close to the underlying reason why:

Conservatives don’t, and won’t, fund art which challenges, subverts, and provokes, because the conservative mentality (even when it is incarnated in people whose politics are not conservative) is, above all things, concerned with avoiding disturbance.12

All beauty disturbs. It reaches through the bubble of the normal and induces a dream-state. It pulls the beholder out of himself at the same time that it forces him down into the depths of his own soul, and connects the two together. The more integrity an artwork displays, the more difficult it is to resist its pull into the dream-state it weaves.

As a means to avoiding disturbance, conservatives of all stripes concern themselves with enforcing orthodoxy.

To Build Culture

All art which emerges from an artist is subversive.13 It re-makes the subject of the art in some fashion. It communicates a vision that is unique to the one who produced it. And, if it has integrity, it shows something new in the space where its subversion acts—even if, as in the stories of H.P. Lovecraft, or the novels of Albert Camus, or the films of David Fincher, that “something” is a void that evokes in the audience an awareness of its smallness, or a glimpse at the tragedy of life, or a thought about what the world would be like without that which was undermined.

Where culture is concerned, all artists are eventually forgotten. We don’t know anything about Homer, we only know his epics (probably a heavily edited and synthesized version of them). Hundreds of years of diligent Biblical scholarship have left only question marks and educated guesses about the men who wrote the Bible. Some learned scholars seriously debate whether Shakespeare actually wrote the plays attributed to him. All artists eventually fade like waves on the beach, leaving only their mark on the sand, which, if they are very lucky, may last only as long as their civilization (and its children) persist.

It is that vision that endures.

And those artists whose subversive visions and wacky ideas and dissolute lifestyles build up the cultural soil in which you grow, are all quite, quite mad.

The fact that you may be more comfortable with visions spun by a warrior, a murderer, or a drunk than you are with the tapestries woven by adulterers, cads, rapists, drug fiends, pedophiles, kinksters, racists, or homosexuals—or vice versa—is no credit to your standing as a moral being. It merely shows you to be a completely conventional in your morality (according to your subculture), of no more independence of thought than a dog who enjoys doing as he’s bidden.

And just because you are conventional in your morality is also no strike against you. If you weren’t thusly conventional, you’d have trouble navigating the world in which you live.

Assuming that you are of a generally affable nature and value the company of other humans, being unconventional and freethinking in your moral outlook will see you readily to a life of pain, as you are quietly shuffled out of one close community after another any time those communities grow large enough to begin sorting members by ideology rather than affection.

In such a life, you might find yourself forever on the fringes, or cast into the outer darkness and walking between the night’s lamp halos, telling the tales of a madman to those whom you meet in the next pool of light. Tales which will be heard, and disbelieved, and enjoyed for their strangeness until those who live in the light begin to feel your tales touching on things they have buried within themselves...at which point you will find yourself on your next journey between lamp posts.

You might, in other words, become something of an artist.

And then you, too, can build culture.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also want to check out my Unfolding the World series, a history of the current geopolitical storm rocking our world, its roots, and its possible outcomes.

When not haunting your Substack client, I write novels, literary studies, and how-to books. You can find everything currently in print here, and if you’re feeling adventurous click here to find a ridiculous number of fiction and nonfiction podcasts for which I will eventually have to accept responsibility.

This is a big part of how I make my living. If you’re finding these articles valuable, please kick some cash into the offering plate!

Hubris, you will recall, is the cardinal sin in ancient Greek theater and literature.

i.e. the worship of a supreme god in a cosmogeny containing many gods. A full write up is available at the New World Encyclopedia.

By the definitions of those words at the time, these criticisms were accurate. It’s a delicious irony to contemplate that anytime someone attempts such a subversion of Christian tradition they get castigated as “Satanic.” But then, we all tend to think we get a moral pass for such blasphemies, while our enemies should be held to the strictest standards. Sic Semper Est [i.e. it is always thus]. But I digress...

Published last year on HollyMathNerd’s page

Aristotle, Politics 2.1272a 22–24ff

In no particular order: Drunkenness, whoremongering, child murder, polygamy, adultery, murder, homosexuality, necromancy, genocidal warfare, circumcision of the dead, etc.

Please note I said “Mightiest,” not “Greatest.” The latter invokes moral categories and value judgments. The former merely observes the fact that it is the English branch of Western civilization that has produced the two most powerful multi-generational empires in world history (the British and American) whose influence touched every corner of the globe, including the lands that they did not directly rule.

I’m not going to go into whether the Woke and their fellow travelers caused this—that is a long and complex conversation which deserves its own article.

In some cases, such as with gender bending and abortion, the rates actually have gone up. In other cases, such as with promiscuity, the rates have gone down after a brief upward tick. In still others, as with homosexuality, the rates have stayed more-or-less constant.

You will find this dynamic at play in every significant era that is notorious for its hedonism, from Imperial Rome after Augustus to Weimar Germany. In literally every case, hedonism sets in after a culture has already lost its foundational rationale. Check out Camille Paglia’s Sexual Personae for a complete catalog of such eras throughout Western history. See also Toynbee’s A Study of History.

For a solid (if woefully incomplete) catalog of some of these struggles written from a Conservative Christian perspective, see William D. Romanowski’s book Pop Culture Wars.

Good art which is called “conservative,” such as the directorial efforts of Mel Gibson, or the novels of Andrew Klaven, routinely get derided by conservative critics for “excesses” in so-called “offensive” content like violence, sex, nudity, and terror. These artists may be conservative in their politics, and conservative in the sense that they love the historic traditions of the West, but they are not conservative in their mentality—it’s clear from listening to them speak at any length that they are also, like the rest of us, quite mad and quite ungovernable (at least by anyone but themselves).

I except from this “all” the faithful reproduction of religious iconography. While it is an artisinal job that requires high levels of technical excellence, it does not leave much room for creativity or interpretation. The demands of fidelity of reproduction removes the artist’s individual vision from the process.

Great article! Scatology, didn't know that word, glad I do now. The culture wars seem to really be punishing childrens literature. Or perhaps as much is the change in which the most "successful" children's writers are not writers, but celebrities holding the reader hostage in their particular moral vision. And we've also become really focused on "representation" in characters and I'm curious about your thoughts on that. If a child's connection to a character is assumed to be "you look like this character, adopt all their virtue" it seems to miss the opportunity to identify with some type of otherness , whatever that may be (physical, moral, circumstantial) and grow. One of my favorite movies growing up was the sandlot, and the movie did not need a girl in the gang for girls to love it, it would have been fundamentally changed, and that story could be told but as it's own thing (bad news bears?)

Great essay, Daniel. Read it twice—and that’s probably not enough.

You might petition the gods of Substack to suggest the following rule when formatting articles: Footnotes should be in square brackets (“[ ]”) immediately following the text to which they are attached. When reading a substantial essay like yours—at least 20 screenloads—reading a footnote and then finding your way back becomes burdensome.